The Marshall Islands UBI: An Experiment That Buys Time but Tests the Limits of Policy

Input

Modified

The Marshall Islands UBI brings short-term relief but long-term risk Cash works early, yet universal programs strain small economies Success depends on governance and timely adjustment

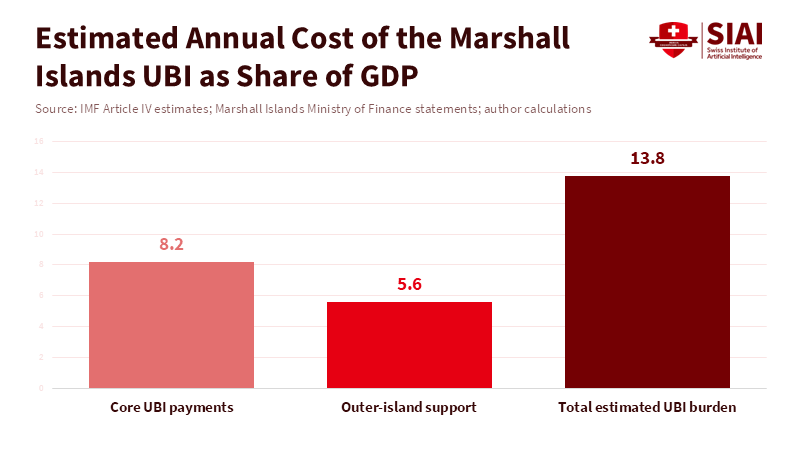

In November 2025, the Marshall Islands launched a universal basic income (UBI) program for all citizens. Each person gets about US$200 every quarter. While this amount is small, the total cost is significant. Early budget estimates show the UBI could use over 8% of the country’s GDP each year, and with extra support for the outer islands, this could reach nearly 14%. Most countries would likely reject this level of spending. But in the Marshall Islands, a small economy that depends on imports, trust funds, and outside help, the main question is whether the program can last. The UBI is more than a welfare policy; it is a test of financial stability, government management, and political will. Supporters see it as a caring response to instability and climate risks, while critics worry it could become a long-term problem. Both sides have valid points.

Rationale Guiding the Marshall Islands UBI Experiment

The Marshall Islands UBI, known locally as Enra, was designed to solve a specific political and economic problem. The country has limited formal employment, high living costs, and deep geographic fragmentation. Delivering targeted welfare across dozens of remote atolls is expensive and slow. A universal transfer avoids complex eligibility rules and ensures that support reaches households quickly. In that sense, the policy is pragmatic rather than ideological. It reflects a belief that imperfect cash delivered fast is better than perfectly targeted aid that arrives late or not at all.

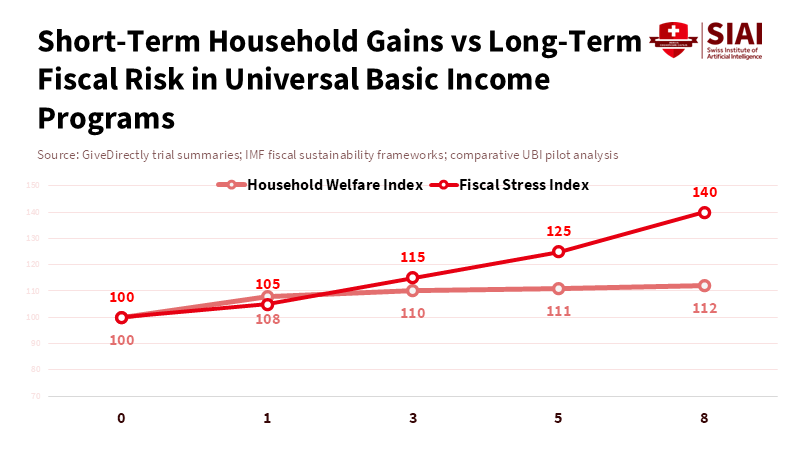

The Marshall Islands UBI will probably meet its short-term goals. Studies from other cash transfer programs show steady gains in food security, family stability, and mental health. Early feedback from the islands shows people are spending the payments on food, fuel, school costs, and basic household needs. These are everyday expenses, not luxury items, in an economy where prices often change, and incomes are uncertain.

The main worry is what happens over time. Universal basic income works best as a short-term fix, not a permanent solution. Big countries can adjust or stop policies that do not work, but small countries have a harder time making changes. Once everyone gets a benefit, it is tough to reduce or end it, even if money runs short. This means the Marshall Islands' UBI puts the country on a careful path where long-term success depends on steady leadership.

Evidence from Global UBI Initiatives

Advocates of a universal basic income often cite recent pilot programs to argue that concerns are outdated. Broad studies conducted between 2019 and 2024 suggest that unconditional payments do not cause widespread workforce withdrawal. Recipients tend to maintain similar working hours while reporting reduced stress and improved financial planning. Furthermore, municipal trials in high-income nations demonstrate gains in health and stability, even with relatively small payment amounts.

Though these results are important, they are sometimes misinterpreted. The majority of these pilot programs are externally funded and have set time limits. They serve to evaluate household behaviors, not a nation's financial sustainability. Economists expressing doubt about UBI typically do not argue that providing financial assistance to individuals is unhelpful. Rather, they question governments’ capacity to sustain such aid indefinitely without compromising other priorities.

The Marshall Islands UBI is a key example in this debate. Its size compared to the whole economy is much bigger than most pilot programs. The real comparison is not with a city trial, but with a full national budget. If trust fund returns drop or outside aid falls, the government may have to pick between keeping the UBI or paying for health care, schools, and roads. These tough choices are not always clear at first, when money is steady and people support the program.

The idea of opportunity cost must also be taken into account. Funding allocated to universal payments is unavailable for targeted programs. Some research suggests that unconditional payments yield limited long-term benefits for children unless paired with investments in schools, health services, and local support systems. In small island nations, where public resources are constantly strained, shifting resources away from institutions could undermine the very systems that enable sustainable development.

This reality does not suggest that the Marshall Islands UBI is inherently flawed. It suggests that its success must be evaluated by more stringent standards. The central question is not whether households will experience improvements next year, but whether the country will have greater stability and resilience in ten years. Without defined adjustment protocols and financial protections, even a well-constructed program can become fragile over time.

Policy Entrenchment Risks

The biggest risk to the Marshall Islands' UBI is not a sudden economic crisis, but the program becoming too permanent. Once people get used to regular payments, leaders feel strong pressure to keep them going, even if things change. This often happens with social policies, especially in small countries where everyone is closely connected, and news travels fast. This matters because Enra’s funding is not certain. Trust funds go up and down with the global market. Tokenized bonds depend on investors’ trust and stable rules. Outside partners can also change their minds. These are real risks in the world’s financial system. If the UBI cannot be adjusted, it could go from helping the country stay stable to making it less secure.

This is where policy design plays a decisive role. If the Marshall Islands UBI follows explicit financial rules, such as linking payments to multi-year average returns rather than annual performance, it can better handle economic disturbances. By including scheduled reviews or automatic scaling mechanisms, reductions can be interpreted as adherence to established rules rather than political reversals. Transparency plays a role here. Citizens are more apt to accept adjustments if they possess prior knowledge of the constraints.

The program also creates an incentive to upgrade administrative systems. Digital wallets and blockchain payments can lower transaction costs, but they necessitate cybersecurity capabilities, digital skills, and institutional trust. Should these systems falter or exclude vulnerable populations, faith in the policy will decline, harming not only the UBI but public institutions more generally. The Marshall Islands UBI, therefore, encourages a broader consideration of state capabilities. Financial support alone cannot substitute for effective governance. It can, instead, provide time to develop it. If this time is not spent strengthening institutions, the long-term result may be disappointment rather than resilience.

Lessons for Educators and Policymakers

For educators, the Marshall Islands UBI is part of the background, not a direct means of changing schools. Still, it will affect classrooms. A steady family income can help students attend school more often, reduce stress, and enable families to buy needed school supplies. Schools should watch these changes closely. Tracking attendance and student progress can show if stable income leads to better education.

Policymakers should avoid viewing the UBI as a replacement for public investment. In fact, available evidence suggests the opposite. Financial assistance proves most useful when schools, clinics, and infrastructure operate smoothly. If universal payments replace spending on these systems, long-term outcomes could worsen despite short-term gains in welfare.

For administrators, maintaining credibility is key. Releasing transparent financial projections, stress tests, and adjustment policies is not merely a procedural detail, but rather a political necessity. The Marshall Islands UBI will only sustain public confidence if citizens believe it is managed honestly and responsibly. Silence and optimism cannot substitute for transparency.

Global observers should be careful when making conclusions. The Marshall Islands is not a model for big countries facing job losses from artificial intelligence. Instead, its lessons are for small states with little ability to raise taxes and high risk from outside events. For these countries, a universal basic income is not a perfect solution or a mistake. It is a risky experiment that needs careful management.

The Marshall Islands UBI is already helping families and easing short-term problems in a fragile economy. This alone makes it worth studying. But its real value is in testing if a small country can turn limited outside resources into a lasting social agreement without risking its future. Knowing the risks is not the same as handling them well. What matters most are strict financial rules, openness, and responsibility. If these last, the UBI could show that universal payments buy time to adjust. If not, the program will still teach us about the limits of policy in a world full of challenges.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

East Asia Forum. 2026. The price of the Marshall Islands’ universal basic income. East Asia Forum.

The Guardian. 2025. Marshall Islands launches world’s first universal basic income scheme offering cryptocurrency. The Guardian.

IMF. 2025. Republic of the Marshall Islands: Staff concluding statement of the 2025 Article IV mission. IMF.

London Assembly. 2023. Universal Basic Income trial findings. London Assembly.

NBER. 2024. E Vivalt, The employment effects of a guaranteed income. NBER Working Paper.

RNZ Pacific. 2025. Marshall Islands introduces world’s first crypto-based universal income scheme. RNZ Pacific.

Stockton SEED. 2023. Guaranteed income results from the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration. Results4America catalog.

UNDPRBAP. 2024. Universal Basic Income in Asia and the Pacific: policy brief. UNDP Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific.

Wikipedia. 2025. Economy of the Marshall Islands. Wikipedia.

Wikipedia. 2025. Marshall Islands. Wikipedia.

Comment