Charging the Trade War: Why Chinese EV Batteries Explain the Failure of Tariffs — and What Comes Next

Input

Modified

EU tariffs raised EV prices but did not erode China’s dominance in battery production Chinese EV batteries stay competitive due to scale, cost, and integrated supply chains Without parallel investment in skills and capacity, trade measures invite retaliation without resilience

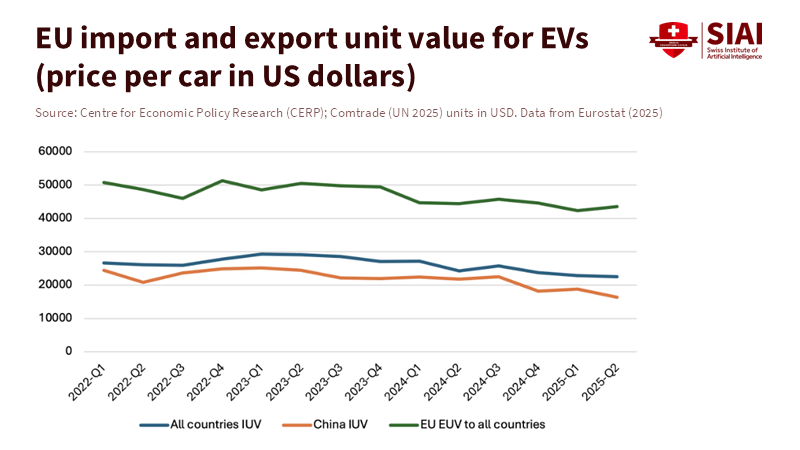

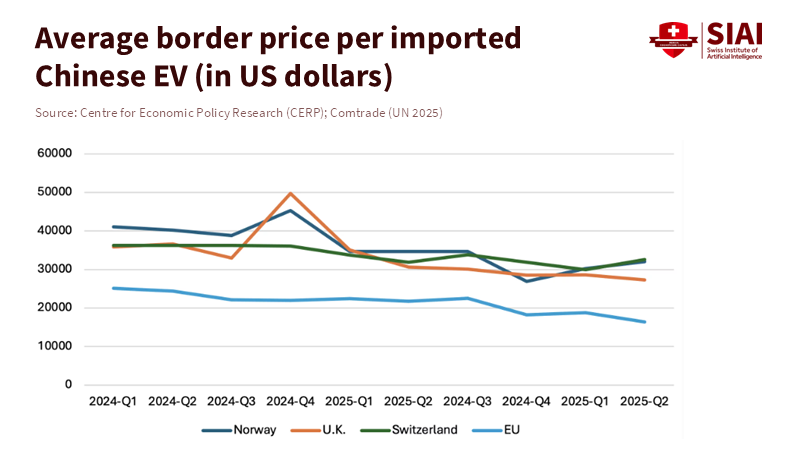

In 2025, tariffs on China's subsidized electric vehicles (EVs) did not reduce the dominance of Chinese battery cells and packs in Europe. About two-thirds of global EV battery manufacturing is still based in China, and over half of EVs imported into Europe rely on Chinese battery suppliers. This situation reflects global market realities, not an attempt to avoid tariffs. While tariffs increased vehicle prices, they did not change how batteries are sourced or integrated. Policymakers focused on imported cars, but the real competition happens earlier in the supply chain, at the battery stage. The continued dominance of Chinese batteries shows why tariffs have little impact, often lead to quick retaliation, and raise costs without delivering significant benefits.

Chinese EV Batteries: Understanding Market Dominance

Chinese EV batteries lead the global market thanks to years of large-scale production, not just one policy. Over the past decade, China has expanded its battery manufacturing capacity faster than anywhere else. By 2024–2025, Chinese companies will have made about two-thirds of the world's EV batteries. This scale matters. Bigger factories are more efficient and lower the cost per battery. High production volumes help companies learn faster, improve efficiency, and reduce defects. These advantages build over time, making it difficult for others to catch up without steady, coordinated effort.

Cost trends reinforce this dominance. The global average price of battery packs fell sharply in 2024 and 2025, approaching the well-known $100-per-kilowatt-hour target. In China, some battery types cost even less. Since batteries make up the biggest part of an EV’s cost, these price differences matter more than moderate trade barriers. Even a 20–45% tariff on finished vehicles can be offset if the battery pack is much cheaper, keeping the final product competitive. Car companies can change their profit margins, logistics, or car models, but the battery cost advantage stays.

Technology choices matter too. Chinese manufacturers started making lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries earlier and at a faster pace than others. LFP batteries have lower energy density, but they cost less, are safer, and last longer. For most vehicles, these trade-offs are acceptable. This means the batteries are cheaper to produce, easier to scale, and meet more consumer needs. In contrast, European and American companies focused on nickel-rich batteries, which are more expensive and depend on volatile raw material markets. This widened the cost gap as more people bought EVs.

Importantly, the dominance of Chinese EV batteries isn't just about the battery cells themselves; it's about the entire production process. Chinese firms control the initial processing of materials, cell production, module assembly, and often the final battery pack integration. They operate in connected industrial areas where suppliers, engineers, and logistics providers work together. This ecosystem advantage is hard to replicate quickly. Tariffs on cars don't dismantle these ecosystems; they only add taxes to the finished products.

Why Tariffs Didn't Work

Tariffs didn't stop Chinese EV batteries because they targeted the wrong part of the supply chain. The European Union imposed tariffs on imported electric vehicles from China, expecting that higher prices would reduce imports or encourage companies to find other suppliers. Instead, the market adapted. Car companies continued to buy batteries from Chinese suppliers and treated the tariff as a cost of doing business. In some cases, they moved assembly locations but continued to source their batteries from the same Chinese suppliers. The physical location of assembly changed, but the reliance on Chinese batteries didn't.

There are two common explanations for this. One is that Chinese batteries are simply too cheap, undercutting the competition even after tariffs are added. The other is that Chinese batteries offer great performance, reliability, and dependable delivery that competitors can't match on a large scale. In reality, both explanations are true. Low cost and strong capability support each other. Cheap batteries capture market share, leading to further learning and investment, which in turn improve capability even more. Tariffs affect prices, but not these reinforcing cycles.

This matters because it limits what higher tariffs can achieve. If cost is the main issue, some policymakers may believe that raising tariffs further will close the gap. But battery economics suggest otherwise. Higher tariffs make retaliation more likely and push up consumer prices, which reduces political support. At the same time, Chinese producers continue to become more efficient and find new ways to export. The policy ends up costing more while offering fewer real benefits.

If strong capabilities and a solid industrial ecosystem are the main reasons for Chinese dominance, tariffs are even less effective. You cannot remove these strengths with taxes. They must be matched or replaced, which takes time, investment, and skilled workers. While this is happening, tariffs can only slow down progress, not change its direction. Even worse, tariffs can discourage cooperation and supply deals that could help companies find new sources.

The fast retaliation in 2025 highlights this risk. Measures against electric vehicles led to countermeasures in other sectors, like agriculture. These responses did not hurt Chinese battery makers. Instead, they spread the political and economic costs to European industries and consumers. The trade conflict grew wider, not smaller. The main goal of reducing dependence on Chinese EV batteries was not achieved.

A Better Policy Approach

If Chinese EV batteries are the critical point, policy should shift away from border measures and toward building domestic capabilities. This doesn't mean abandoning trade protection completely, but it does mean changing priorities. The three most important areas are skills, procurement, and industrial coordination.

First, skills: Making and integrating batteries requires specialized knowledge in chemistry, engineering, and industrial operations. Europe does not have enough experts in these areas. Universities, training centers, and adult education programs should treat battery knowledge as essential. Short courses can train technicians, engineers, and procurement staff in battery chemistry, safety, supply chain analysis, and cost assessment. This is not just theory—it directly affects buying decisions, factory results, and government oversight. Without skilled workers, battery factories will stay as plans, not real assets.

Second, procurement: Government purchasing shapes markets. City fleets, public transportation, and government-funded vehicle programs can create steady demand for locally assembled battery packs, without the need for outright bans. Procurement rules can require companies to disclose the origins of their batteries, provide transparency into their sourcing, and meet targets for local assembly within a specified timeframe. These requirements should be realistic and temporary. The goal isn't to force localization at any cost but to provide emerging suppliers with predictable sales volumes so they can grow, learn, and compete. If done carefully, procurement can help bridge the gap from dependence to diversification.

Third, industrial policy: Making batteries requires large investments and usually stays in one place. Incentives help, but they are not enough on their own. They must be combined with easier permits, good access to electricity, and workforce planning. A battery plant without skilled workers or steady power cannot compete. Government support should be conditional and given in stages, with funding released only when other key needs are met. This approach reduces the risk of wasted money and public disappointment.

Importantly, none of this requires isolation. Diversifying away from Chinese EV batteries doesn't mean excluding Chinese firms entirely. Joint ventures, licensing agreements, and minority investments can transfer knowledge while keeping production local. The goal is resilience, not complete self-sufficiency. A diversified supply chain is less vulnerable to disruptions and political pressure.

Addressing Concerns and the Cost of Delay

Critics say moving away from tariffs and toward industrial policy is slow and expensive, and that's true. Building capabilities takes time. However, delays also have costs. Each year of inaction increases dependence and makes it harder to adjust later. The choice isn't between an easy solution and a difficult one; it's between managing the transition proactively and being forced to react later. Another worry is that industrial policy can cause inefficiency. This is a real risk, and past failures show the need for caution, but doing nothing is not the answer. Policies should be clear, temporary, and measured against set goals. Support should drop as companies get stronger. Firms that do not perform should not get endless protection. Strategic policy should not be a blank check.

Some argue that Europe should simply accept Chinese dominance in batteries as the price of rapid decarbonization. This view underestimates the political realities. Dependence creates weakness, influences negotiations, limits responses, and causes opposition when disruptions occur. A transition that seems controlled by outside forces will struggle to maintain public support. Resilience isn't just an abstract idea; it's essential for maintaining legitimacy.

Finally, some may say that tariffs were politically necessary, and that could be true. They showed concern and gave some breathing room. But this time, only matters if it is used to build alternatives. Without a real plan to develop local capabilities, tariffs are just a short-term fix that can lead to more conflict. The events of 2025 show how quickly this can spread to other industries, raising costs without solving the main issue.

The ongoing presence of Chinese EV batteries in Europe is not just a policy failure; it reveals where real power is in today’s supply chains. Tariffs focused on cars, but the real advantage is in batteries. As long as this gap remains, trade measures will fall short. They will raise prices, trigger retaliation, and keep Europe dependent. A better approach begins with recognizing this reality. Batteries are a strategic asset, so policy should focus on education, procurement, and industrial investment. Skills need to be built, demand guided, and production capacity expanded. Trade protection can help, but it cannot replace the need to build real capabilities. In a long trade war over electric vehicles, everyone loses. China, Europe, and consumers all pay the price. The only lasting benefit comes from reducing risk through diversification and learning. The case of Chinese EV batteries shows why the current approach has failed and what must change.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BloombergNEF. (2025). Battery pack price survey 2025.

Bruegel. (2025). Europe’s battery manufacturing challenge.

Eurostat. (2025). Trade in electric vehicles and components.

Reuters. (2024–2025). EU–China trade measures and retaliation.

SNE Research. (2025). Global EV battery market share and capacity.

S&P Global. (2025). Battery chemistry and cost trends.

Comment