The Role of Tariff Incentives in Policy: Emphasizing Strategic Patience over Punitive Measures

Input

Modified

Tariffs may work for semiconductors, but they fail as a broad industrial policy Volatile tariff revenue signals deeper economic and institutional costs Punishment-based trade erodes trust that long-term investment needs

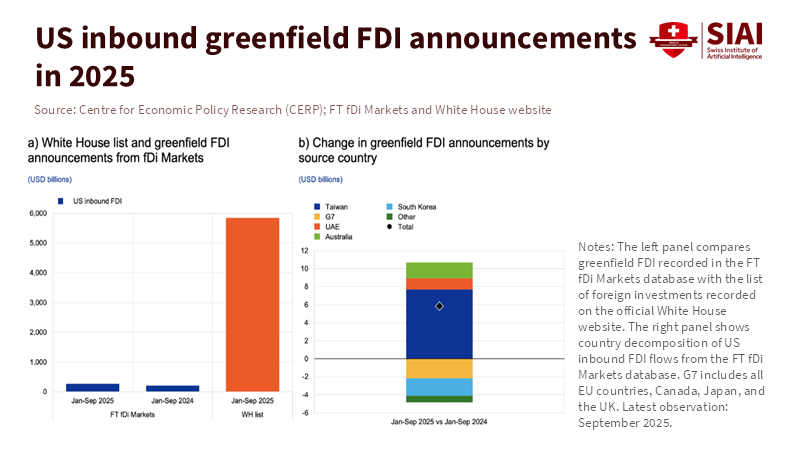

The U.S. government’s $52.7 billion investment in the CHIPS and Science Act aims to attract advanced semiconductor manufacturing, but it also brings risks. At the same time, federal customs duties dropped from about $108 billion in 2022 to $77 billion in 2024, then rose again after policy changes in 2025. This up-and-down pattern raises an important question: Can broad tariffs really replace steady investment and partnership efforts as tools of national industrial policy? Tariffs might make sense in certain cases, like semiconductors, where the U.S. market is influential and trade policy can shift incentives. However, using punitive tariffs more widely creates big problems. What looks like leverage can actually lead to unpredictable budgets, higher costs for schools and families, and weaker ties with international companies and key allies. Recent revenue disruptions, investor uncertainty, and reduced trust from other countries highlight these issues.

The Semiconductor Exception and the Application of Tariff Incentives

To really understand this issue, it’s important to see that subsidies and tariffs are not always opposites. In fact, they can work together. Subsidies provide direct financial assistance and reflect what the government values, while tariffs function as taxes that alter market prices. In semiconductors, subsidies have worked well because the industry requires a lot of upfront capital, long development times, and serves mostly domestic customers. The CHIPS and Science Act, which set aside about $52.7 billion for semiconductors, is a good example. By the end of 2024, the Commerce Department had awarded over $33 billion to projects in several states, with major incentives going to big companies like TSMC, Intel, and Samsung to build or expand factories. These results show that public funding can influence private companies’ decisions about major national projects.

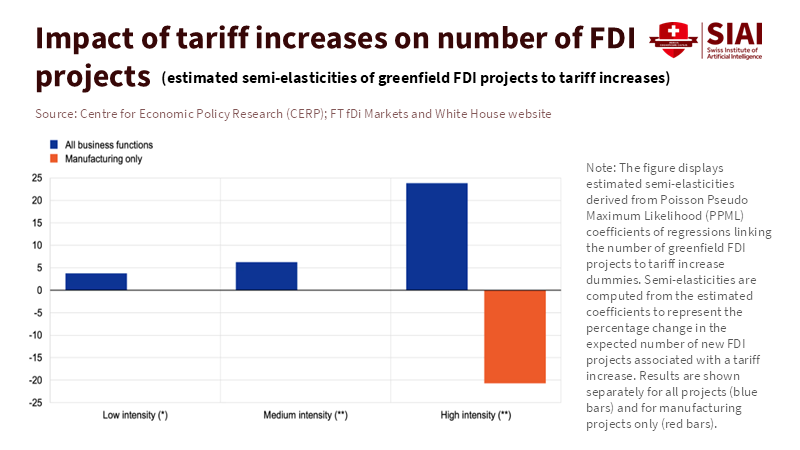

Selective tariffs on inputs or final products within a specific sector can serve as incentives by increasing the cost of accessing the U.S. market unless production is relocated domestically. This rationale supports the targeted application of tariff incentives. However, even in such cases, significant risks persist. The semiconductor industry, for example, is deeply embedded in global supply chains, with components frequently crossing international borders. Taxes imposed on final imports may be circumvented or absorbed earlier in the production process. Firms may reconfigure supply chains to mitigate the intended impact or redirect investments to jurisdictions with more favorable regulations. In conclusion, while targeted tariffs may be justified within a comprehensive policy framework aimed at specific industrial objectives, their effectiveness relies on precise regulations, rigorous enforcement, and robust countermeasures. These requirements are challenging to sustain when tariffs are broadly implemented.

Wider Economic Impacts: Instability, Costs, and Erosion of Trust

The real threat arises when tariff incentives move beyond isolated measures for sectors like semiconductors and become a widespread practice across numerous areas of trade. Historically, customs duties have accounted for a small but volatile share of federal income. The drop in customs duties from their 2022 peak to a lower level in 2024 shows that tariff revenues can change drastically in response to policy, trade volume, and accounting methods. Basing investment strategies on expected steady tariff revenues assumes a consistent revenue stream amid volatility. The impact on public finances, including schools, hospitals, and universities that depend on reliable funding, is significant, as revenue instability makes long-term financial planning more difficult and more cautious.

Economic considerations exacerbate existing political challenges. Broad-based tariff increases elevate import costs, which are subsequently reflected in consumer prices. Preliminary analyses indicate that substantial tariff hikes are likely to marginally reduce GDP growth, increase inflation, and lower real wages, thereby directly impacting households and public institutions, including those in the education sector. International partners may retaliate or strategically distance themselves. Multinational manufacturers, whose investments the government seeks, may interpret such policies as heightened political risk. These firms must then choose between accepting increased operational uncertainty in the U.S. or investing in countries perceived as more stable, where long-term agreements and cooperative relationships are more reliable. This scenario is evident in the way suppliers and investors evaluate political risk alongside factors such as labor costs, infrastructure, and market access. Ultimately, broad tariffs supplant stable partnerships with unpredictable coercion.

Effects on the Education Sector

The education sector should also be aware of the broader economy, as the policy implications go beyond manufacturing and trade balances. First, the immediate price increases caused by broad tariffs raise operating costs for schools and universities. Imported laboratory equipment, computers, classroom materials, and food services become more expensive. Institutions facing tight budgets might respond by reducing hiring, limiting course offerings, and raising student fees. Second, research partnerships suffer due to the policy. University laboratories depend on international supplier networks for specialized resources and on international collaboration for skills and projects. Tariffs can slow procurement, raise costs, and create more legal disputes. Third, workforce development programs, such as apprenticeships, co-op arrangements, and university-industry relationships, rely on companies that are ready to make long-term investments. When trade policy is used as a tool of punishment, companies might reduce commitments, postpone expansions, or shift investment away from the U.S., reducing options for students and limiting employment opportunities. Each of these outcomes has occurred in recent months as companies and procurement officers adjusted their expectations regarding costs and partner reliability.

Another effect is on what and how students are taught. As industrial policy becomes more one-sided and unpredictable, students need to learn flexible supply-chain management skills. Schools should help graduates learn to navigate changing supply chains, understand and manage geopolitical risks, design robust procurement plans, support faculty development, build industry partnerships that account for risks, and focus on hands-on learning with local employers less affected by trade issues. College leaders should act on these steps soon. While these changes won’t fix all the big economic problems, they can help reduce the negative impact of sudden policy changes.

Addressing Counterarguments

Some argue that tariffs are good political tools because they are fast, easy to see, and can force change. But acting quickly without careful thought raises costs for everyone. While higher tariffs may raise customs revenue at first and help pay for public goods, this benefit is short-lived. Tariff revenue can drop as imports change, companies pass costs to buyers, or courts overturn the policy, as happened from 2022 to 2024. Depending on unstable tariff income, long-term plans can leave funding gaps when business habits shift. The main advice is: Policymakers should not base long-term strategies or public budgets on shaky tariff revenues. Instead, they should look for steady, reliable funding. Gains from tariffs are often offset by higher costs, lower productivity, and slower growth, all of which reduce tax revenue and public services over time.

To minimize these damages, avoid relying on tariffs as a default negotiating tool. Instead, prioritize maintaining reliable commitments and fostering trust among foreign partners. This approach will protect the reputation and long-term stability of sectors like semiconductors, where trust and close coordination are crucial.

Some people say tariffs can be targeted and reversed. While this is possible in theory, it takes clear rules, strong administration, and international teamwork—things that often break down when tariffs are used for short-term political reasons. If tariffs are part of a bigger plan, they must be managed closely, measured openly, and matched with investments that protect public trust and funds. Otherwise, we risk the costs of protectionism and the unpredictability of harsh actions.

Sustaining Connections

The real decision for policymakers is how to approach economic statecraft. When public finance is carefully applied to sectors such as semiconductors, with regular evaluations, performance-based conditions, and workforce development programs, it creates real, valuable commitments. On the other hand, when tariffs are widely used across the broader economy, they yield small gains at the cost of heavy losses. The revenue reports have shown revenue instability, and policy reversals can temporarily boost revenue but undermine lasting investments that schools, companies, and communities need. Even more concerning is the effect that punishment has on working relationships, which breaks supply chains and prompts investors to move their capital to a safer environment. Education leaders and administrators should respond by safeguarding their procurement from price shocks, teaching students to develop geopolitical and supply-chain resilience, and strengthening long-term partnerships with companies by setting enforceable commitments. Policy makers should use tariffs carefully, make sure incentives are paired with strict accountability, and restore trust to foster long-term partnerships. If the manufacturing sector is to advance, policymakers must be prepared to fund it with plans that create stability, encourage cooperation, and avoid instability and coercion. Anything other than that leaves us suffering the negative consequences for a long time.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Goldman Sachs. (2024). Market Brief: Taking Stock of the Tariff Shock. Goldman Sachs Research.

International Monetary Fund (as reported). (2025). Tariff surge would damage global growth, IMF warns. Financial Times.

NIST / U.S. Department of Commerce. (2025). CHIPS incentives and award summary. U.S. Department of Commerce announcements.

Reuters. (2024). TSMC wins $6.6 bln US subsidy for Arizona chip production. Reuters.

U.S. Congress / CRS. (2022). CHIPS and Science Act appropriations summary. Congressional Research Service.

U.S. Treasury / Fiscal Data. (2024). Monthly Treasury Statement; Federal receipts and customs duties. FiscalData / Treasury.

USAFacts. (2025). Customs duties revenue historical series. USAFacts analysis of Treasury and OMB data.