The Test of APEC's Standing: Why China's Subsidies for Industries are More Important Than Talk of Free Trade

Input

Modified

China’s free-trade rhetoric at APEC clashes with its ongoing industrial subsidies Without subsidy discipline, regional trust and fair competition cannot recover APEC’s credibility depends on rules, not gestures

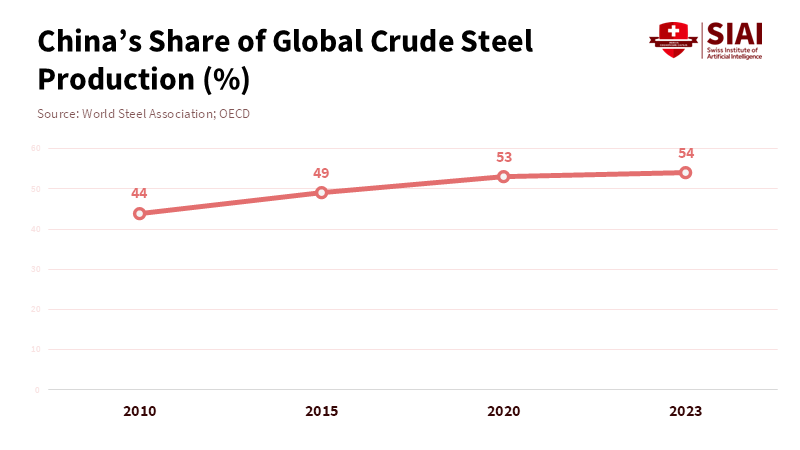

China now produces more than half of the world’s steel, even though global demand has fallen. This shift helps explain why free trade in the Asia-Pacific region doesn’t have the same appeal it once did. Such high production isn’t just about market forces. It’s driven by ongoing government support that shields businesses from losses, makes borrowing cheaper, and encourages output beyond what’s needed. When China sells this surplus abroad, prices fall to levels that unsubsidized companies can’t match. For Northeast Asian economies, this isn’t just a theory—it leads to factory closures, job losses, and new trade barriers. As China gets ready to present itself as a supporter of open markets at APEC, its credibility will depend more on how it handles these policies than on diplomatic statements.

Rethinking Free Trade in Light of China's Subsidies for Industries

The justification for revitalized regional partnership relies on a well-known idea: fewer obstacles, smoother supply chains, and shared economic growth. This idea is particularly important now, as the Asia-Pacific region faces weaker global demand, tighter financial conditions, and rising political mistrust. The idea of free trade, though, has deviated from its original economic meaning. It's now frequently used to defend the movement of products without paying equal attention to the regulations that determine how those goods are made. The needed revision is simple. Open trade isn't just about border taxes. It also concerns the circumstances within a country that affect prices and production ability. China's industrial subsidies are central to this distinction.

Trade rules have long tried to balance openness with some restrictions. Governments could help with innovation or public services, but ongoing support for production was limited because it affected trading partners’ prices. Now, this balance is under pressure. China relies heavily on state involvement—through credit, land, energy prices, and direct funding—to keep costs low and production high, even when the market signals a slowdown. This creates constant oversupply. When China exports the extra goods, it also exports the effects of its subsidies. Calling this free trade stretches the meaning of the term.

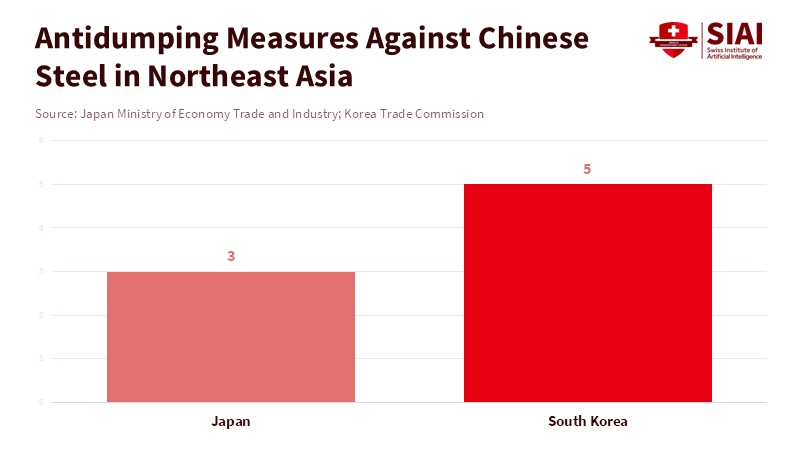

This new perspective helps explain why trust has faded. Japan and South Korea are sometimes seen as slow to open their markets to protect older industries, but their main concern is competing under rules that don’t limit the biggest producer. Without control over subsidies, opening up more just increases the gap. Promises of partnership can feel like being forced to accept another country’s unchecked policies.

How China’s Industrial Subsidies Create Excess Production

The steel sector shows this process very clearly. China's part of global steel production has grown from about two-fifths to well over half in the last 15 years. At the same time, domestic demand has slowed as building construction has reached its high point. In a market economy, this mix of events would cause businesses to combine and reduce production. But instead, production remained high. Businesses could refinance debt and continue operations with very small or even negative profits. The economic reason is simple: when borrowing costs are kept low and losses are shared, businesses delay closing. Production ability then becomes sticky.

This has global effects. The extra steel looks for buyers outside China, which pushes prices down. Even small price changes matter in steel, where profits are slim and volumes are huge. Producers in Japan and South Korea have been hit hard, facing imports sold for less than it costs to make them. Their governments respond with investigations and tariffs, since these are the only options under current trade rules. These aren’t acts of protectionism—they are ways to bring prices closer to fair market value.

This issue isn’t limited to steel. The same pattern appears in chemicals, aluminum, shipbuilding, and parts of the clean energy sector. In each case, government support keeps production high, global prices drop, and other countries respond with new barriers. This cycle strains partnerships and makes any trade plan that ignores subsidies seem doubtful. For countries like Japan and South Korea, which can’t push back politically because of regional tensions, technical fixes are used instead of tackling the bigger problems.

Why Japan and South Korea Need Action, Not Just Words

Government officials in Tokyo and Seoul face a difficult political situation. Manufacturing is still very important for employment, exports, and technological progress. Communities that depend on heavy industry feel the effects of price changes quickly. When factories shut down, the negative effects are clear and focused. Promises of future benefits from openness are vague and uncertain. In this situation, talking about free trade doesn't mean much unless it comes with real protections.

Geopolitics makes the options even more limited. Unlike the United States or the European Union, Japan and South Korea have less room to maneuver due to strategic constraints. Openly fighting back could create problems in a region already dealing with security issues. Because of this, they take narrow, legal actions, such as imposing duties on unfairly priced imports. These actions show their unhappiness without causing major political conflict. But they also highlight a deeper issue: the feeling that current regulations aren't enough when subsidies are used so widely and secretly.

Because of this, any Chinese plan at APEC will be judged on its real actions. Symbolic claims of leadership may appeal to smaller countries seeking stability, but they won't convince those who are suffering from overproduction. They believe that free trade that ignores industrial subsidies isn't fair. It shifts the adjustment costs to countries that can least afford them. Until this imbalance is fixed, trust will stay low, and efforts to partner will stall.

APEC’s Chance: Regulating China’s Industrial Subsidies

APEC can’t enforce rules like a court. Its influence comes from setting agendas and encouraging members through peer pressure. This makes it a good forum to rethink expectations about subsidies. The aim isn’t to end all industrial policy—many countries support innovation and stability. Instead, the goal is to clearly separate acceptable support from actions that keep excess production flowing into exports.

A practical approach would begin with transparency. Members should agree to share more information about their industrial support, including how much is given, how it’s provided, and which sectors benefit. While transparency alone won’t fix all distortions, it reduces confusion and makes it harder for businesses to deny issues. The next step is monitoring. APEC could set up a system to spot sudden jumps in production in sectors with weak demand, especially when government funding is involved. This wouldn’t be punitive—it would serve as an early warning, allowing discussions before problems grow.

The third part is helping countries adjust. APEC should recognize that changing subsidy policies takes time and should allow affected partners to take temporary protective measures while reviews are done. This would give Japan and South Korea a better option than taking action on their own. It would also reassure smaller countries that openness doesn't mean they have to suffer without any help. For China, the benefit would be to its reputation. By working with this type of system, Beijing could show leadership by limiting its actions rather than by increasing its size.

Some will say that this plan interferes with a country's sovereignty. But trade partnerships have always involved limits on what countries can do. Tariff agreements, standards, and dispute-resolution mechanisms all constrain a country's policy choices in exchange for predictability. Regulating subsidies is a natural extension of this idea. Others will say that China's support is strategic or environmental in nature. That may be partly true. The answer is to make distinctions. Support for real innovation or change can be time-limited and subject to conditions. Support linked to production that creates oversupply should not be allowed.

From Words to Standards: Restoring Trust

The challenge facing APEC isn't about intent—many leaders genuinely want renewed partnership. The real issue is aligning promises with tangible actions. When "free trade" only removes tariffs while subsidies distort prices, doubt is justified. Restoring trust demands standards that address the entire trade context, not just border measures.

China stands at the center of this issue due to its size. Leadership in a rules-based system depends not on export volume but on willingness to accept constraints. If Beijing defends subsidies while urging others to open up, resistance will mount. However, if it makes its policies more transparent and reviewable, new opportunities for partnership will emerge.

For Japan and South Korea, the rewards would be real. Clearer regulations would reduce the need to constantly take actions against unfairly priced imports and lower the domestic political cost of participating. For the region, it would ground partnership in a shared sense of fairness. APEC can't force this outcome, but it can present it as the price of credibility.

The opening statistic about steel production shows what's at stake. Size without limits changes markets and politics. If APEC allows the language of free trade to continue to drift from its real meaning, it risks becoming a place for managing disagreements rather than creating partnerships. By focusing on China's industrial subsidies, the forum has a chance to reverse this trend and renew what openness means for the Asia-Pacific region.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

International Monetary Fund. Trade Implications of Industrial Subsidies.

OECD. The State of Play of Industrial Subsidies.

World Steel Association. World Steel in Figures.

Japan Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Antidumping Investigation Reports.

Korea Trade Commission. Trade Remedy Statistics.

Comment