The Impact of Chinese Industrial Subsidies on Global Competition

Input

Modified

Chinese subsidies have tilted global markets in favor of state-backed firms WTO rules have failed to keep pace with this shift Fair trade now depends on coordinated reform and enforcement

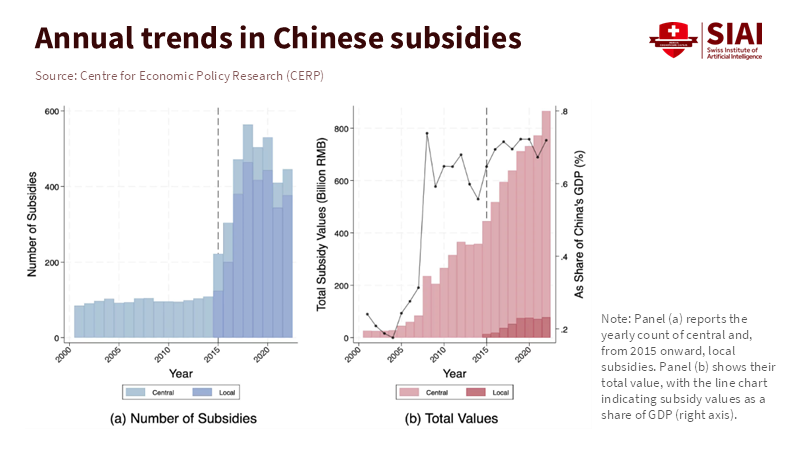

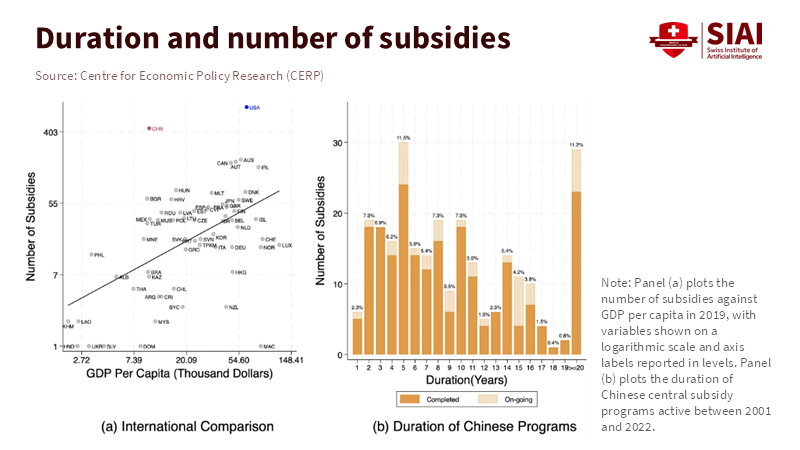

In the last decade, China’s industrial policy has had a big impact on global markets and caused major changes. From 2001 to 2022, the number of Chinese subsidy programs reported grew from 85 to 446. Most of this support now comes as below-market loans and targeted grants. Subsidies have also increased worldwide, with the OECD estimating about USD 108 billion in support in 2023. These subsidies have shifted production and exports, giving China a strong advantage. As a result, exporters in countries like Germany, Japan, and South Korea have lost market share and profits in areas such as solar panels and electric vehicles. The World Trade Organization (WTO) is struggling to address these new and complex types of support. The main question now is not whether subsidies matter, but how democracies should respond when a major economy uses public funds to reshape global industries.

Chinese Industrial Subsidies: The Mechanics of Gaining an Advantage

China’s industrial subsidies have grown in both size and type. Reports show that China now tells the WTO about hundreds of programs, up from just dozens before. The OECD says most of the recent global increase in subsidies comes from grants and cheap loans. These supports do more than help single companies—they lower market prices, speed up capacity growth, and shift supply chains toward producers who get the most help. When competitors get cheap financing or payments to boost output, price competition gets tougher in the short term. Over time, these changes are reshaping the whole industrial landscape.

Subsidies cut production costs and let subsidized exports sell for less than foreign competitors. Countries that import these goods might use countervailing duties, but they have to prove the subsidies are targeted and have caused real harm, which can take a long time. Today’s subsidies often use complex financial tools, making them hard to spot and enforce, and this leads to uneven results.

The impact of subsidies varies by sector. In industries where size and experience matter, like solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles, Chinese companies have used cheap loans and grants to quickly become top suppliers. The IEA says China made about half of the world’s electric car sales in 2021, and by 2024, this grew to almost two-thirds. Chinese OEMs made about 70% of China’s car exports in 2024. This growth is not just normal market change—it is targeted, export-focused, and supported by the state. For countries that used to lead in high-value engineering and capital goods, this means lower profits and less manufacturing strength.

The Victims: Competing Exporters and the Limits of Current Rules

The costs of these changes are clear. Germany, Japan, and South Korea rely a lot on manufacturing exports and supplier networks. In the past 10 years, Germany’s car industry has faced more competition from cheaper Chinese cars and parts. Reports show rising job risks and a need for quick policy changes in Germany’s auto sector. Japan and South Korea have also seen pressure in electronics, batteries, and other industries where Chinese subsidized production has grown fast. These are not isolated cases—they show that subsidies are shifting global industrial capacity.

Why haven’t WTO rules fixed these problems? The SCM Agreement was made for simple cases like tariffs and export rebates. Now, industrial support is more complex and often comes from state banks, local programs, or complicated tax and buying schemes. The WTO can handle straightforward cases but has trouble when details are missing. The WTO has said China’s reports do not give enough detail, making it hard for other countries to prove their cases. When facts are unclear, governments are less likely to act, so local companies face losses or wait years for help.

Because of this, subsidies act like a reverse tariff. Instead of hurting exporters, they give subsidized producers a cost advantage. This often breaks WTO rules and is unfair to countries that play by the rules. China uses the WTO system to challenge other countries’ actions, even though its own subsidies are hard to track. This uneven approach weakens trust in global trade.

Policy Response: What Democracies Can and Should Do

Policymakers have three main choices: accept the shift in industrial capacity, take protectionist actions, or work together to improve international rules and spot unfair subsidies. Accepting the decline means giving up, which brings high social costs. Acting alone with tariffs or countervailing duties could lead to more trade disputes and may not help workers and suppliers quickly. A better approach is to build domestic resilience and update global rules. Resilience means diversifying supply chains, investing in advanced skills, and giving temporary support and retraining to affected workers. Still, resilience alone is not enough—rules must be updated to deal with large-scale subsidies.

A modernized set of rules should include better transparency requirements. Countries should report not only the number of programs but also the financial scale, eligibility criteria, and price differences for concessional finance. The SCM Agreement’s definitions of specificity and prohibited subsidies need to be updated to include widespread below-market finance and repeated layering of local programs that act as national industrial policy. Dispute settlement needs to be faster for subsidy cases in which harm is evident and measurable. The international community should expand cooperative monitoring through an independent subsidy observatory. It would be built on company-level disclosure and third-party verification to reduce the information gaps that allow hidden support to continue. These steps are achievable and defensible because they seek to restore the promise of equal treatment that underlies the GATT/WTO.

A strong policy response means governments need to act clearly both at home and internationally. Democracies should avoid copying broad, hidden subsidies, but can make targeted investments in important technologies with clear oversight. Countervailing duties should be used carefully and coordinated to avoid unnecessary trade disputes and focus on real harm. International finance groups can help by offering open, market-based loans to competing firms, reducing the need for more subsidies. These steps would help keep industries competitive, lower the risk of subsidy wars, and support fair trade.

Policy with Principle and Strength

Today, state spending shapes trade competition more than innovation does. Democracies need to protect their industries and workers while pushing for WTO reforms that increase transparency and update rules on modern subsidies. If action is delayed, factories will close, and skills will be lost. The goal is not to be protectionist, but to restore fair competition by updating the rules. This is an urgent challenge—if nothing is done, unchecked subsidies could permanently change global industry.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

CEPR. Two Decades of Chinese Industrial Subsidies.

OECD. Industrial Subsidies and State Support: Recent Trends.

World Trade Organization. Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures.

Third World Network. Subsidies, Trade Rules, and Development.

International Energy Agency. Global Electric Vehicle Outlook.

Comment