The New Comparative Advantage: How Multinational R&D Shapes Innovation

Input

Modified

Multinational R&D specialization routes research, engineering, and production to best-fit locations Heckscher–Ohlin logic links talent hubs with supplier clusters and scalable manufacturing Schools should buy for resilience and upgrades, favoring evidence-backed, diversified supply chains

A single statistic explains why the location of innovation now dictates success. In 2024, the top 2,000 global companies invested approximately €1.44 trillion in research and development, accounting for over 85% of all business-funded R&D. China accounts for about 29% of worldwide manufacturing value, whereas Israel invests about 6% of its GDP in R&D, the highest rate in the OECD. These facts form the pattern: firms that distribute the innovation process across borders—locating basic science where expertise is abundant, applied development where suppliers are quick, and production where costs are minimal—see performance gains. This is a multinational R&D specialization, a key element for global success. Organizations that understand this will shape progress in education tech, manufacturing, green hardware, and AI learning in schools and universities.

Heckscher-Ohlin in the 2020s: Why Multinational R&D Specialization Matters

The traditional Heckscher-Ohlin model says that countries export what they have in abundance. In today’s knowledge economy, this includes research talent, strong supplier groups, and efficient production systems. Multinational R&D specialization links each stage of the innovation process to these strengths. Companies might conduct science in Tel Aviv or Zurich; co-develop parts with Korean or Japanese partners; test designs near Shenzhen; and mass-produce in the Yangtze River Delta or Mexico’s Bajío. The goal is not just to move work, but to match each task to the place that best ensures success and speed.

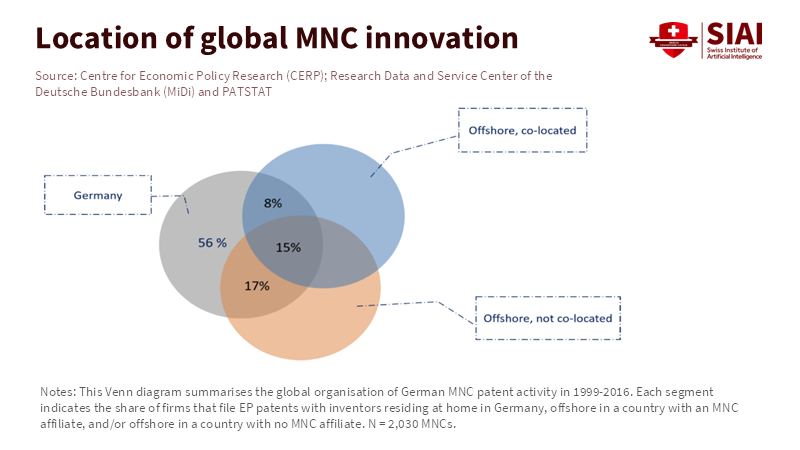

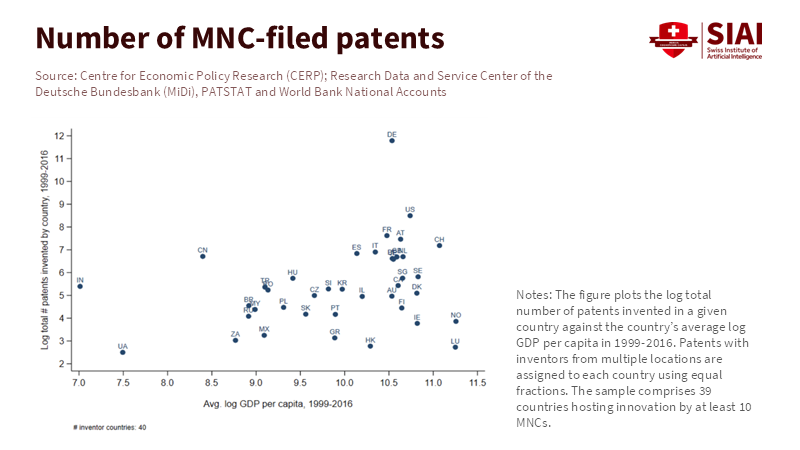

The advantages include better patents, faster product cycles, and greater stability. Data from German companies show that larger global firms obtain more high-quality patents across many countries, even where they lack branches. Basic research happens overseas more than people realize, and applied R&D often occurs near production. This is important because more production options can boost innovation at home and overseas. The production landscape changes constantly. China’s share of global manufacturing output is around 20%, with reports showing ongoing activity despite ups and downs. Meanwhile, global firms like Huawei, Samsung, and Qualcomm lead in international patent filings. In short, production capacity and innovative ideas are separate. Strategy must join them.

From Patents to Production: How the Model Functions

Multinational R&D specialization works by relieving key bottlenecks: limited talent, long supplier times, and high capital costs. First, talent is key. Israel’s R&D spending has been around 6% of GDP, the highest among OECD countries. This supports early work in areas like cybersecurity and learning data. When new algorithms or privacy methods are needed for learning tools, being near research talent speeds things up. Second, suppliers are crucial. Placing applied engineering near manufacturing areas makes it easier to quickly change designs. UN data from 2024–2025 show Asian manufacturing growing even as other areas slow. The result is that engineers can quickly go from testing to full setup. Third, capital and risk matter. Most business R&D is done by a few big companies because scale lowers costs if projects fail. Data shows the top 2,000 global companies account for most of the world’s business R&D. These firms can take multiple chances, which keeps product plans moving when one idea does poorly or a part faces export rules. They can also use policies to their advantage. Business R&D is often supported by tax breaks across the OECD, which encourages firms to put work where it can be done quickest. This results in a system that assigns tasks to countries just like a computer assigns operations to processors.

For education, these dynamics have specific implications. Devices and AI in classrooms will come from companies that spread out work: basic model work in areas with universities and funding, and applied engineering near suppliers in Asia or Europe. This can shorten the time it takes to get a product from testing to classrooms.

Smart Policies for Multinational R&D Specialization

If specialization drives progress, rules keep things in order. Policies should support basic research, keep development close to suppliers, and allow flexible production without risking important tech. Start with research. Countries that do well invest in R&D, offer public funding, and have open immigration for researchers. The OECD shows that businesses account for about three-quarters of R&D; public policy should reduce risks without taking over private investment. Education ministries should link grants and purchases to learning outcomes and privacy, not just to appealing projects.

Next, for engineering and suppliers, governments cannot recreate all suppliers at home. They can speed up approvals and standards for trusted partners. Quick systems for classroom tech should include security checks and clear information on materials. If security requires local production, policies can permit specialization. Parts could come from one partner, assembly in another, and security audits at home. The aim is to keep schools supplied with reliable, affordable tools.

Finally, production flexibility is key during geopolitical stress. It is better to reduce risks than to cut ties completely. This means companies should have options, build in two areas, use pre-approved parts, and make export-ready versions of products. Reports show that the production map is shifting, with Europe and Asia expanding or contracting at different times. Schools that rely on a single-area supply may face delays. It is better to require backup plans and reward suppliers with diverse, checked supply chains.

Addressing Concerns About the Model

Three common concerns arise: that multinational R&D specialization harms domestic jobs, that it leads to intellectual property leakage, and that reliance on foreign production is risky. Each has some truth, but can be managed with the right rules. Regarding jobs, data show that firms with diverse production networks also get more patents. The appropriate response is to support technical colleges that connect students to supplier groups.

Protecting intellectual property requires safeguards, not separation. Countries with strong IP rules and global ties lead in patent filings. Firms can protect code and data even when assembly is overseas. Governments should set rules for model management and security, rather than forcing all production to be onshore. This keeps science open and protects key assets.

When it comes to risk, redundancy is better than self-sufficiency. Supply disruptions are real, but the answer is to diversify. Schools should ask vendors for manufacturing and logistics plans that can survive disruptions. Multinational R&D specialization enables devices to be designed by researchers from different countries and assembled in different locations, making the product more resilient because it is global.

What This Means for Education

When schools buy a platform, they gain access to a development pipeline. Teachers who use a tool are affected by a global process. Schools should seek proof of success across different markets. Multinational R&D specialization enables firms to test features quickly across multiple locations. Purchase for potential upgrade and invest in teachers as co-developers. The advantage of countries with strong education systems is the feedback they provide. Create pathways for teachers to send data back to R&D teams, thereby aligning products with classroom needs. Connect purchases with specialization. Give credit to vendors that show strong supply chains, privacy, and research practices.

For a national strategy, countries should focus on their strengths: talent, suppliers, or production capacity. Support basic research at universities, make it easier for applied research labs, and cultivate talent for quality control. This is not a race to the bottom, but a move toward partnership.

Combine Ideas and Scale

Top firms fund most business R&D. Manufacturing is focused on a few areas. The process between them influences what is used in schools. Multinational R&D specialization organizes this process. It matches tasks with resources and supports idea growth by placing science, engineering, and production where they work best.

Education needs innovation, prototypes, and production, along with rules to ensure security and fairness. Organizations that follow this model will shorten product cycles and protect their values. The alternative is to keep changing purchase plans while the world moves forward. Plan for multinational R&D specialization, buy accordingly, and regulate with it in mind. That is how to turn ideas into affordable learning at scale.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bloomberg (2025). Germany Is Just Making Too Much Money in China to Back Away Now. November 16, 2025.

CEPR VoxEU (Gumpert, A.; Manova, K.; Rujan, C.; Schnitzer, M.) (2026). Multinational firms and global innovation. January 7, 2026.

Financial Times (2025). UK companies on list of top R&D spenders almost halves in a decade. January 2025.

Financial Times (2026). Why China is doubling down on its export-led growth model. January 2, 2026.

Financial Times (2025). VW considers closing factories in Germany and cutting jobs. September 2024.

JRC European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard. December 2024.

JRC European Commission (2025). The 2025 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard. December 2025.

OECD (2024). Main Science and Technology Indicators: Highlights. March 2024.

OECD (2025). R&D tax incentives continue to outpace other forms of government support for R&D. April 2025.

Reuters (2025). Chinese buyers interested in unwanted German Volkswagen factories. January 16, 2025.

UNIDO (2024). World Manufacturing Production, Quarterly Reports 2024. 2024–2025.

UNCTAD (2024). World Investment Report 2024. June 2024.

UNCTAD (2025). Global trade hits record $33 trillion in 2024. March 2025.

WIPO (2024). PCT Yearly Review 2024.

WIPO (2025). PCT Yearly Review 2025 Executive Summary.

World Bank (2024). Manufacturing, value added—China.

Comment