Let’s Stop Pretending Outright Bans Will Save Children from Social Media

Input

Modified

Social media bans for children shift teens to riskier apps Use age assurance + safe defaults + measurable outcomes Make protections portable across platforms and schools

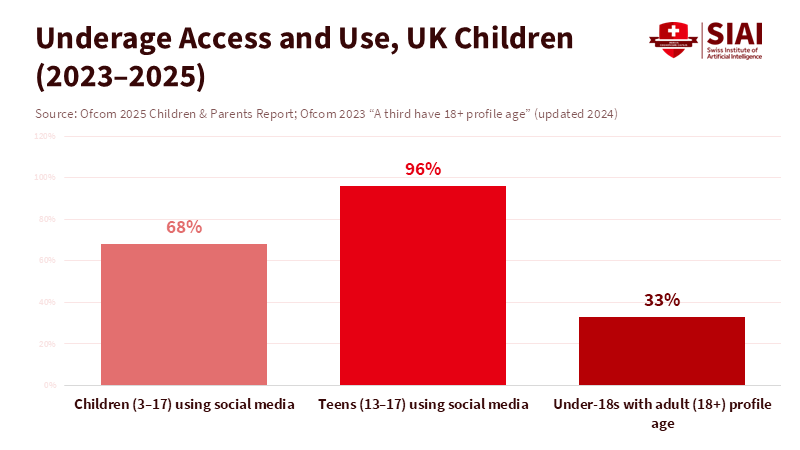

Young people have already shown what happens next. In the United Kingdom, 40% of 8–17-year-olds admit to lying about their age to access social media accounts. Many also recognize that they engage in other risky online behaviors. This statistic should guide the discussion about banning social media for children. If nearly half can bypass age restrictions on popular platforms, outright bans won’t stop usage; they will just shift it elsewhere. Australia’s new regulation, effective December 10, 2025, requires major platforms to lock accounts for users under 16. Within days, downloads of lesser-known apps increased, many of which lacked moderation, collected more user data, or encouraged private sharing. Europe is looking at similar measures, and New York has implemented warning-label requirements. However, these warnings do not reach children in closed groups or on offshore services. The risk is clear: bans might reduce visible harm on major platforms but can push real harm into less-regulated, hidden spaces.

The Policy Test We Keep Failing

The debate treats social media as a simple switch to turn off for young people. It isn’t. It comprises design choices that influence attention, feelings, and identity, all within a market seeking to avoid obstacles. Social media bans for children aim to cut off access to mainstream content. They fail to eliminate the instincts that drive use: peer influence, performance, novelty, and the need to belong. When the Australian rule went into effect, the enforcement message was loud. Ten major platforms faced legal actions and fines if they allowed under-16 accounts to continue. The optics were strong. Yet the policy assessed success at the entrance rather than in the spaces where teens actually spend their time. Early reports from Australia noted a rise in alternative apps climbing the local charts. Some of these operated outside familiar safety systems and provided poor reporting tools. If current behavior continues, teens will combine VPNs, web-based clones, and messaging channels to recreate the same social network within weeks.

For this reason, the current wave of proposals across Europe should rethink fully adopting the ban model. France plans to prohibit under-15s from accessing social media starting in September 2026, and to extend phone bans into high school. Several EU nations are considering similar measures, and Brussels has provided guidance under the Digital Services Act, advocating for “appropriate and proportionate” protections for minors. The European Commission has even tested an age-verification app in five countries, aiming to sync checks with the new EU Digital Identity Wallet. These initiatives highlight a more complicated reality: effective enforcement requires a multilayered safety net, including design standards, default settings, verifiable controls, and measurable results. The main policy question is not just whether to ban but whether new regulations will lead teens to safer features and environments or push them into a grey market of imitation services with fewer safeguards.

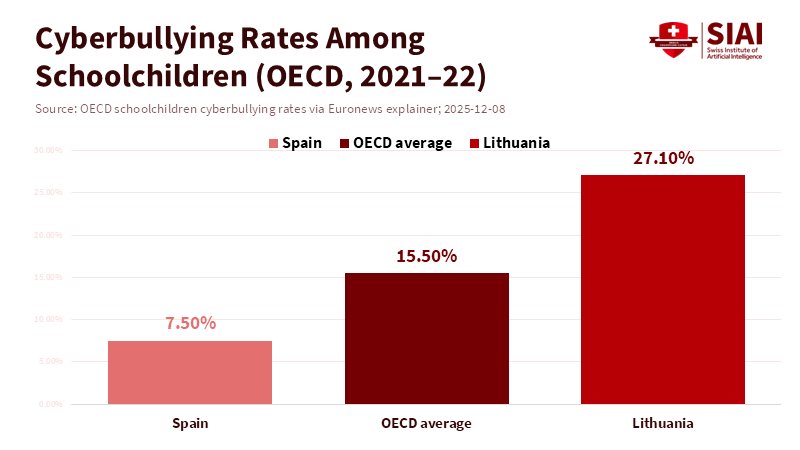

The Evidence, Reframed Around Harm—Not Hours

Public debate keeps circling back to screen time. That focus is too simplistic. Reviews from 2025 summarize dozens of studies and find no clear evidence that time spent online alone directly harms mental health. The stronger links are with specific harms: cyberbullying, unwanted contact, sexual exploitation, and exposure to self-harm content. When we concentrate on hours, we miss the extremes. A small portion of teens exists in high-risk environments where harmful interactions happen quickly and often. Social media bans might cut average hours on popular platforms, yet they can leave those extremes untouched or push them to spaces with weaker moderation and faster escalation. That’s not the right exchange.

A better approach is to adopt a harm-pathway perspective that addresses both design and context. This aligns with current EU initiatives under the Digital Services Act, which go beyond labels and checklists to require platforms to address risky patterns at the system level. Features such as autoplay, infinite scrolling, and “people you may know” recommendations should be limited for minors. Default privacy settings must be strengthened to block unsolicited contact. Recommendation algorithms should be built to downrank content related to self-harm, eating disorders, and revenge porn, rather than relying only on user reports. When these features are mandated by law, platforms that do not comply may face fines or be required to change their products. This strategy better aligns regulatory needs with real-world evidence by targeting and reducing interaction patterns linked to harm.

What Actually Works: Design, Identity, and Literacy Together

If bans alone don’t work, what solution is effective? Start with age verification that protects privacy and works across platforms. Europe’s pilots suggest device-level or wallet-based checks that confirm a broad age group (for example, under 13, 13–15, 16–17) without revealing identity. Australia’s enforcement illustrates why this matters: when under-16 accounts were locked on major apps, the easiest option wasn’t to stop using social media; it was to switch to apps with weaker or no age checks. If we fortify the area around mainstream options while leaving side channels open, harm will simply move. The goal is to make basic age checks portable across services and hard to spoof, while still protecting minors’ data. This makes it tougher for unsafe apps to compete based on looseness.

Next, manage addictive design patterns like New York now does—with clear, visible warnings—but take it further. Labels are just the beginning. The more effective approach is to add default friction. For minors, turn off autoplay by default, cap features that encourage compulsive behavior, delay rewatches of stimulating clips, and add hurdles before sharing images outside of a friend group. These aren’t just theoretical requests. Many are in the recent guidelines and have been tested in real environments without compromising the user experience. They remove the “slot machine” aspect from the core loop for young users. Schools and families can implement daytime curfews, sleep-friendly modes, and restricted quiet hours. But these measures will only be effective if platforms offer them as primary features and if minor accounts are identified and maintained in that protected status.

Finally, digital literacy programs should address narrative and social risks, not just data verification. Teens are more influenced by stories than by statistics, and misinformation and bullying often spread through narratives and group dynamics. Educational programs should teach students to recognize the dangers of “challenge” videos, understand how rumors can spread quickly, and use built-in safety features without worrying about social consequences. These lessons should be part of school curricula and parent workshops. Also, platforms should include brief, context-sensitive prompts that disrupt potentially risky posts or encourage teens to rethink messages before sending. When these prompts are enabled by default for minors, digital literacy becomes an active safeguard rather than a passive lesson.

What Schools and Systems Should Do Next

The immediate choice for education ministries and districts isn’t between freedom and restrictions. It’s about preventing a quiet shift to hidden platforms and actively ensuring that mainstream options are safer—and demonstrably so. The strategy should be clear. First, structure social media bans for children around tiered access rather than a single hard line. Under-13 accounts should remain blocked from general-purpose social networks, consistent with child protection standards. Ages 13–15 should only be allowed on accounts verified as minor accounts, with built-in friction: no public discoverability, strong default privacy settings, no algorithmic friend suggestions, and limited daily push notifications. Ages 16–17 can unlock certain features with guardian controls and clear audit trails. This is a gradual approach, not an all-or-nothing scenario.

Second, shift compliance from paper-based to data-based. Governments should demand quarterly reports from major platforms showing child safety metrics: the proportion of minors on minor accounts, the enforcement rate for unsolicited contacts, the volume and response time for bullying and sexual exploitation reports, and the percentage of minor accounts with friction features activated. These metrics should be auditable by independent organizations and standardized across platforms. New York’s label law is a start; a stronger move would be to require red-team tests on recommendation systems and publicly share the findings. The EU’s DSA provides a legal basis for this requirement. Australia’s enforcement experience shows the importance of clear timelines and fines. The key lesson is that what gets measured gets managed—and what isn’t measured gets manipulated.

Third, assist schools with purchasing and teaching. Many districts now rely on third-party apps for learning and communication. Vendor contracts should require minor-account modes, age-verification compatibility, and clear moderation commitments. At the same time, curriculum teams should include short, repeated lessons on social risks—five minutes at the start of a term, ten minutes before exams, and scenario practices after significant online incidents. The goal isn’t to impose morals but to practice strategies that reduce harm during stressful times or when group pressure increases.

Critics will argue that anything less than a total ban is giving in. However, the practical view is that broad bans will create a large gap between what policymakers believe is happening and where teens actually spend their time. This gap can lead to serious harm. A targeted ban specifically for the youngest children, enforced through reliable age verification, along with strict design guidelines and measurable results, can keep that gap from appearing. This approach is not softer; it is smarter.

Anticipating objections and responding with policy

One objection is that bans send a message about social values: childhood should be free from persuasive technology. The message is important, but policies must also address actual harm. If the message drives teenagers to unregulated spaces where abuse is hard to detect, it becomes a costly signal. Another concern is that age-verification tools can threaten privacy. This risk is real if the tools require identity documents or store sensitive data in a single location. Europe’s strategy suggests a better approach: providing a grouped age locally on devices or through digital identity wallets with limited data exposure. This method emphasizes privacy by design. A third concern is that restrictions will stifle innovation. In reality, high-quality products already minimize risks for younger users. Clear rules establish a foundation and make compliance easier. They reduce legal uncertainty for companies investing in safer designs.

Another criticism suggests that warnings and labels are ineffective. Static warnings, by themselves, are weak. However, New York’s regulation should be seen as part of a larger change: it calls for disclosures, alongside product limits and care metrics that regulators can check. When companies face penalties for failing to reduce measurable risks, labels become part of a broader enforcement system. The strongest criticism focuses on the thin evidence base. Social media constantly changes; today's platforms differ from last year's. This is precisely why rules should target basic risks like unwanted contact, compulsive behaviors, and harmful groups rather than specific brand bans. The evidence about these risks is stronger and more consistent over time, even as apps change.

Finally, some claim that social media bans for children are effective in Australia and that the emergence of alternatives is merely a temporary trend. Perhaps. But if the trend continues, we may spend less time on major platforms while increasing screen time on other sites. Without reliable age verification and consistent design standards across platforms, there is no reason to expect this trend to reverse naturally. Children will follow their friends, and markets will respond to demand. The key question is whether public policy will ensure safety wherever they go.

Address what children actually use

Returning to the initial fact, nearly half of children admit to lying about their age to access social media. A policy that expects full compliance while ignoring this reality will likely fail and could push risks out of view. Australia’s rule is a significant milestone, but it should be seen as a test for the future. Europe's guidance and pilot identity programs, along with New York’s warning-label law, provide a potential path toward layered protections. The next step is to bring these elements together. We need to view mainstream platforms as engines of safety rather than as scapegoats. We should enforce privacy-preserving age bands, automatically limit addictive design for minors, publish clear harm statistics, and make digital literacy an ongoing part of the experience, rather than a worksheet.

We can choose to measure success by how many accounts of under-16s vanish from popular apps. Alternatively, we can measure success by how much bullying, exploitation, and harmful content fails to reach children, no matter where they go. The latter approach is more challenging, but it aligns with how young people actually use the internet. Social media bans for children draw attention. In contrast, safer design, portable age verification, and validated outcomes will create real change. The policy goal should not be to drive adolescents from one platform to another. Instead, it is to reduce harm wherever groups gather and keep those gatherings in safe spaces.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, December 26). New York to require social media platforms to display mental health labels.

Australian eSafety Commissioner. (2025). Social media age restrictions: Key measures under the new law.

European Commission. (2025, July 14). Guidelines on the protection of minors under the Digital Services Act.

Internet Matters. (2025, December 4). New data shows no rise in children’s VPN use after online age checks.

Ofcom. (2024, April 19). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2024.

Reuters. (2025, December 10). Australia begins enforcing world-first teen social media ban.

Reuters. (2025, December 31). France aims to ban under-15s from social media from September 2026.

UNICEF Innocenti. (2025, May 5). Child well-being in an unpredictable world (Report Card 19).

UNICEF Innocenti. (2025, June 12). Childhood in a digital world.

Verge, The. (2025, July). The EU is testing a prototype age verification app.

Comment