From Populist Start to Effective Governance: The Requirements for Sanaenomics in Japan's Education, Skills, and Stability

Input

Modified

Pivot Sanaenomics from populism to productivity Protect real per-student spending and modernize vocational training Target support, not handouts, to grow without tighter BOJ policy

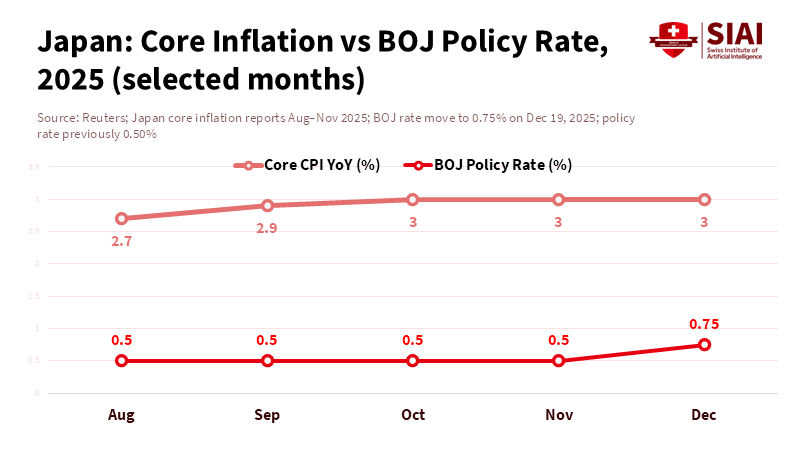

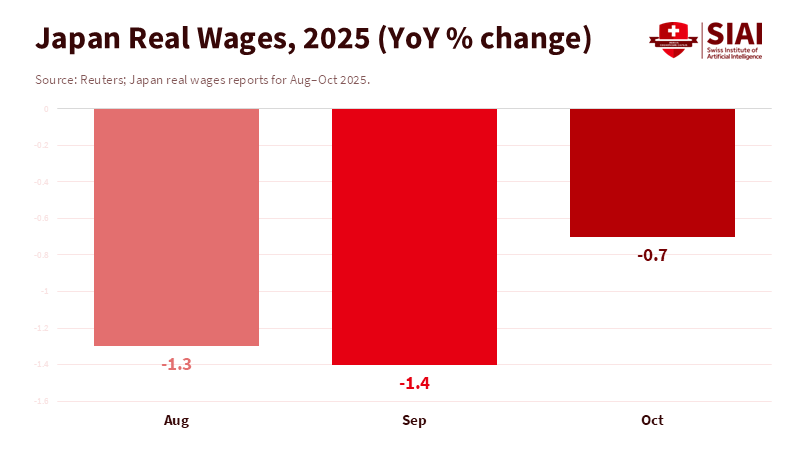

As Japan moves into 2026, it faces a notable contradiction. Sanaenomics promises quick recovery and national strength. The Bank of Japan’s policy rate is at a 30-year high of about 0.75 percent, and core inflation has stayed above 2 percent for almost four years. Pay increases are happening, but real wages have decreased recently. Direct payments and subsidies give some help to families. The amount of money in circulation fell in 2025 as the BOJ ended crisis measures and reduced asset purchases. Opinion polls show mixed approval for the new cabinet, suggesting underlying unrest. These figures matter because they affect the nation’s ability to fund education, attract skilled workers, and improve skills in the long run. For Sanaenomics to succeed, it must change from a popular start to a plan that increases productivity in schools and companies.

Rethinking Sanaenomics: Priority of Reliance Followed by Skillful Implementation

The first few months have resembled an extension of the campaign. They included tax cuts, subsidies, and strong statements that appeal to a tired public. There was logic in this approach. The Liberal Democratic Party’s image had declined. Showing quick results could rebuild trust and stabilize its position. Initial polls suggest this approach worked. Some surveys found support near 75 percent. Others were closer to 60 percent. The message is the same: the public is giving Sanaenomics a chance. The political situation has changed. The LDP’s split from its longtime ally and its ties to a more conservative group increase the possibility that it will trade agreement for firm positions. The danger is clear: strong positions without careful planning can turn into fixed beliefs.

Sanaenomics must now change direction. The deflation strategies of the 2010s will not work in a tight job market, with lasting inflation, and with a weak yen. Even small increases in interest rates raise the cost of debt at a time when the government wants to rebuild defense, support key industries, and help families. When policy rates rise from near zero to 0.75 percent, even small mistakes can cause issues. Popular actions, like handouts and price limits, provide short-term help but do not increase productivity. The focus must shift to improving skills, migration, research, and school funding. These methods are less appealing than direct cash payments, but they increase long-term growth and reduce price pressures without decreasing demand. A governing majority that has public trust should use its political power to focus on skillful implementation, starting with education.

Sanaenomics and the Risk of Stagnation in Education

Education policy connects short-term help with long-term growth. Real wages fell in 2025 even as nominal pay increased, and core prices continue to be higher than the BOJ’s target. The BOJ has made it clear that it intends to normalize policy. Because of this, school budgets that depend on central funding are under pressure from both debt and goods costs. When borrowing becomes more expensive, there is less money available to raise teacher salaries, improve labs, and expand childcare. If Sanaenomics relies too heavily on broad stimulus, the resulting price increases will force tighter monetary policy, diverting resources from schools and training centers. This creates a stagnation in education, where changing policies hurts schools.

However, the data also show an opportunity. Japan’s minimum wage rose sharply in 2024, and companies have reported labor shortages. These shortages exist not only in factories but also in care work, early childhood education, and technical training. Raising pay in these areas is important, but not enough. The country needs a plan to increase the number of teachers and trainers in fields related to key industries such as semiconductors, energy systems, cybersecurity, and advanced manufacturing. Linking funding to long-term workforce agreements among local governments, education boards, polytechnics, and major employers would target resources to where shortages are most critical and align curricula with actual needs. If done correctly, this approach would support real wage growth by increasing worker productivity, rather than by boosting demand in sectors that cannot expand.

There is also a foreign talent aspect that Sanaenomics has not given enough attention to. If Japan hopes to increase growth while its working-age population declines, it will need more international students to stay after graduation and more skilled migrants to enter teacher training and technical education. Public concern about migration is real, but the cost of a closed system is higher. It leads to empty seats in vocational programs, slower spread of new methods, and weaker global research connections. The focus on border security in the first months was understandable as a message to a conservative base. The next step should be a controlled, skills-based migration plan tied to education and training outcomes. That is how a popular start becomes a productivity policy.

From Populism to Policy: A Shift Toward Skills and Immigration for Sanaenomics

This shift starts with rules. First, commit to long-term, inflation-adjusted funding for early childhood and compulsory schooling. The key is to prevent a decrease in real per-student spending as long as core inflation is above target and nominal wages are still catching up. This avoids the cycle in which local boards must cut programs, delay maintenance, and freeze hiring when prices rise. It also protects learning when families face high energy and food costs. Second, use new funding to improve teacher quality and update programs, not for general subsidies. Targeted improvements are more effective than broad handouts. Focus on digital labs in vocational high schools, apprenticeships with industry, and teacher programs that place trainees in schools with shortages while they earn credentials. The goal is job placement that raises productivity, not just processing grants.

Third, create an Education Skills Visa that links international students with local job needs. The idea is simple: give a three-year work permit after graduation in specific fields with shortages, provided they are employed by approved employers and continue their education at polytechnics or universities. Connect the program to regions with significant population decline. Local governments would compete for these students by helping with housing and language support. For a cautious public, safeguards are important. These include initial limits, clear employer standards, and yearly public reviews. The benefit is significant. Increasing the number of foreign graduates expands the teaching and training workforce, increases enrollment in specialized programs, and helps revitalize small cities.

Fourth, connect Sanaenomics' industrial goals with education funding through skills-for-subsidy conditions. If the government invests in chip factories, grid improvements, or port logistics, the companies involved must help fund programs in nearby vocational schools and universities. This changes industrial policy from an isolated effort into a talent pipeline with measurable results, like trained instructors, apprentices, and certified technicians. It also improves subsidy design. Projects that cannot show a clear plan for skills development should not receive public funding.

Finally, protect household budgets without undermining monetary policy. Replace general energy subsidies with income-based credits, and change from one-time cash payments to regular child benefits. When help is targeted and based on rules, it supports families without increasing general demand in a way that forces the BOJ to respond. This protects the money needed to invest in schools and training over the long term, rather than just for immediate needs.

A Practical Assessment for Sanaenomics in 2026

Some may argue that these steps are either too small for a political situation that values intense action or too ambitious for a financial situation tightening as rates increase. Both arguments miss the point. The path from popular support to productivity growth depends on institutions that develop over time, such as teacher quality, modern programs, and targeted migration rules. These are not dramatic, but they are essential. Japan has tried both headline policies and quiet improvements before, but rarely together, and seldom when facing inflationary pressures. The challenge for Sanaenomics is whether the government can manage both financial markets and schools' needs simultaneously.

The political environment will likely remain chaotic. Tense regional issues make tough talk attractive, and a divided parliament leads to tactical battles over symbols. That is why the government should focus on a few clear education and skills goals. By the end of 2026, increase the number of vocational high schools with industry-supported labs. Expand teacher programs in areas with shortages. Secure a specific number of placements through the Education Skills Visa. Monitor real per-student spending against inflation each month. Share the results in a way that the public can understand and the BOJ can trust. This reduces the chance of the kind of populism that mistakes activity for progress.

The choice is clear. If the government continues to rely on payments and price limits, the BOJ will respond with higher rates, which will hurt school budgets and delay improvements that raise living standards. Or, the government can use the trust it has gained to make a change that aligns Sanaenomics with Japan’s strengths: careful public administration, strong local organizations, and a culture that values learning. The issues raised at the start of this article—rising rates, lasting inflation, and decreasing real wages—do not need to define the future. They should define our work. Put skills and schools at the center of Sanaenomics to turn a start into a lasting strategy that improves living standards.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BNP Paribas Wealth Management. “The Impact of ‘Sanaenomics’ on Japanese Equities.” October 22, 2025.

East Asia Forum Editors. “Takaichi’s Short-Term Populist Politics No Cure for Japan’s Structural Malaise.” January 5, 2026.

East Asia Forum Editors. “Sanaenomics’ Fiscal Arithmetic Doesn’t Add Up.” December 8, 2025.

Katz, Richard. “Japan and the Contradictions of Sanaenomics.” East Asia Forum, December 7, 2025.

Mainichi. “2025 Rewind: ‘Foreigner Policy’—and Xenophobia.” December 29, 2025.

Nippon.com (Jiji Press). “BOJ Likely to Pursue Further Rate Hikes This Year.” January 4, 2026.

OECD. Employment Outlook 2025: Japan Country Note. July 9, 2025.

Reuters. “Government Panel Member Urges BOJ to Anchor Inflation Expectations Around 2%.” January 6, 2026.

Reuters. “Japan’s Cash in Circulation Falls for First Time in 18 Years in 2025 on BOJ Stimulus Exit.” January 6, 2026.

Reuters. “Japan’s October Real Wages Fall for 10th Month Despite Upbeat Nominal Pay.” December 7, 2025.

State Street Global Advisors. “‘Sanaenomics’: A Truss or a Meloni Moment?” October 24, 2025.

The Japan Times. “Public Support for Takaichi’s Cabinet Ebbs to 59.9%, Survey Shows.” December 12, 2025.

Japan Forward (Sankei/FNN). “Takaichi Cabinet Records Exceptional Youth Support in Latest Poll.” December 25, 2025.

Xinhua. “Bank of Japan Raises Interest Rate to 30-Year High.” December 20, 2025.

Comment