Central Asia’s Green Transition Will Be Won by the Cheapest Supply Chain—and the Smartest Classrooms

Input

Modified

The Central Asia green transition will follow the fastest, cheapest supply chains The EU can lead on standards, skills, and grid readiness, even if China supplies hardware Central Asia keeps control by demanding open data and local capacity in every deal

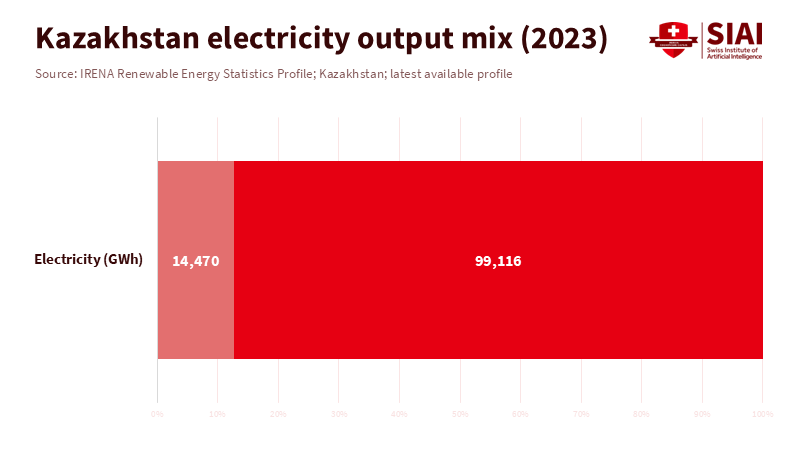

China accounts for over 80% of all solar panel parts, from raw materials to the final product. For Central Asia's move to green energy, this number is more important than any promise of leadership. Solar and wind power rely on shipped goods like panels, inverters, turbines, cables, and batteries, which have delivery dates, warranties, and require spare parts. When the largest clean-tech factory is close by, price and speed become essential. The source of equipment also impacts training, because the supplier often provides the manuals, software, and service teams. A seemingly cheap deal can become costly if local skills and data are not present. This competition is apparent in colleges and control rooms, not just in politics. The winner is often the partner that is on time, can work in harsh environments, and stays within budget. In practice, China’s proximity and low-cost supply chains make it the default supplier in many deals, even when Europe shapes rules and standards. This change is essential because Central Asia is now buying equipment. Kazakhstan has held renewable energy auctions and aims to be carbon-neutral by 2060, but coal and gas remain the primary sources of energy. Uzbekistan is growing fast, with about 1,800 MW of solar and 500 MW of wind power added in 2024 alone, according to IRENA. Developers from the Gulf region are investing heavily and building quickly, often combining finance with Chinese engineering and equipment. This is not just a competition between the EU and China. It is about who can provide low-cost clean energy quickly and help the area maintain control as it grows. The Central Asia green transition will depend on contracts, supply chains, and skills.

Why the EU’s offer for Central Asia’s move to clean energy feels slower

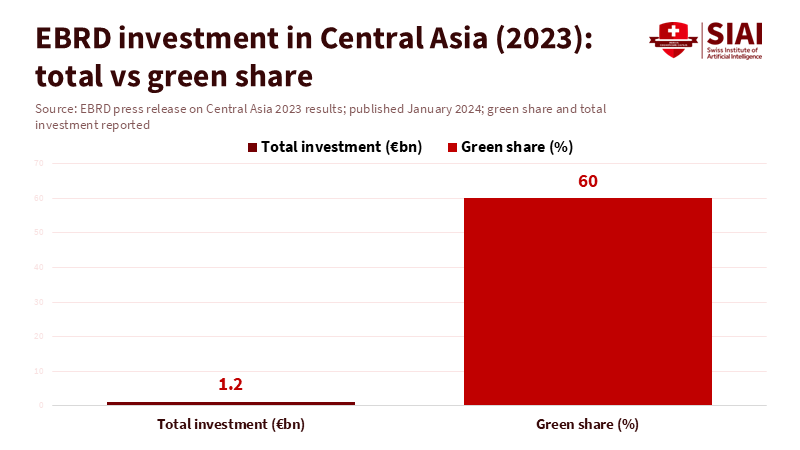

The EU's offer often seems slower to change because it is based on rules. EU-related funding usually requires open bidding, impact assessments, and apparent oversight. This can be hard when leaders face shortages, and voters worry about rising costs. These steps can save money in the long run by lowering the risk of poor projects, hidden fees, and public resistance. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development reports that it invested over €1.2 billion in Central Asian economies in 2023, with 60% of its investments being green. This is not just about ethics; it is about reliable contracts, fewer disagreements, and cheaper funding when trust is strong. EU energy cooperation also depends on technical support, connected to the EU’s Central Asia strategy from 2019 and a joint plan from 2023.

Europe is also trying to expand its primary offering. At the first EU–Central Asia summit in April 2025, EU leaders shared a €12 billion Global Gateway package that included clean energy and critical raw materials. A policy assessment by DGAP adds that in 2024 and 2025, European and international organizations committed €22 billion through the Global Gateway to support lasting links in Central Asia, with a focus on the Middle Corridor. This is important because logistics shape energy costs. They affect how quickly equipment arrives, how expensive transporting turbines is, and how easy it is to service sites far away. It also matters for bargaining power; better routes mean more suppliers can compete.

Some argue that the EU cannot compete with China on price, so it should stop trying. That is incorrect. Europe does not need the cheapest panels to drive the move to clean energy in Central Asia. Instead, it needs to be competitive in areas that cannot be bought, such as grid planning, reliable data, and skill standards. Europe’s partnership with Kazakhstan on sustainable raw materials, batteries, and renewable hydrogen points in that direction. It is about rules, supply chains, and knowledge, not just a single plant. If Europe helps set stronger standards for auctions, permits, safety, and data reporting, it can lower overall system costs, even if the equipment comes from other places. That influence will last beyond election cycles.

How China and Gulf capital are changing how the move to clean energy in Central Asia is funded

China is often seen as prioritizing infrastructure. This is still accurate, but their methods are changing. Chinese companies are still strong in engineering and grid-related work. Yet they are also becoming more involved in the equipment and services used in renewable energy projects. This is important for bargaining power. When one source can supply panels, inverters, and engineers, it can shorten the timeline. It can also set standard technology choices that are hard to change later. That is where the risk of being locked in can start, even if the initial price seems low. It also affects who trains the staff to run the system. In the move toward clean energy in Central Asia, what seems affordable today can become a reliance tomorrow if agreements do not account for interoperability, data access, and local maintenance.

Investors from the Gulf add another aspect. In Central Asia, Saudi and UAE firms often act as independent power producers. They rely on long-term contracts and large plants and can handle early-stage risks. Masdar said in November 2024 that it agreed to develop a 1 GW wind farm in Uzbekistan and had already signed an agreement in 2023 to develop 2 GW of new wind projects there. ACWA Power said in May 2024 that it signed a $4.85 billion deal for what it called Central Asia’s largest wind farm, at 5 GW. These deals can quickly increase capacity, which Central Asian leaders want. They can also pressure regulators to keep up because big projects expose weaknesses in permitting, grid planning, and dispute processes.

There is a risk of becoming dependent over time. Foreign owners can control operations. Single-supplier systems can limit future options. Yet, none of this is permanent. Governments can set bidding rules that favor local service centers, training, and the release of open performance data. They can divide projects into smaller parts so no single firm controls everything. They can ask for a clear plan for grid improvements and managing energy reduction before a project is approved. Central Asia can treat funding as a negotiating tool rather than just a lifeline. That is the real test of staying neutral. If bids require openness and local capacity, then Europe, China, and the Gulf can all compete in ways that protect the public interest. Simple protections help: open technical standards, shared system data, and clear rules for disagreement and performance.

Which education systems must be offered to support Central Asia’s shift to clean energy?

The greatest need in the move to clean energy in Central Asia is now people, not plans. Turbines and panels can be imported, but skilled installers, grid operators, and contract teams cannot be easily imported. The need is diverse. It includes engineers who can model changes and manage congestion. It includes technicians who can maintain equipment in hot and dusty conditions. It also includes public employees who can read contracts and identify problematic terms. When skills are lacking, costs increase. Projects are delayed, equipment breaks and sits unused, and disagreements increase. This is why leadership is changing. The most important advantage is not just who can fund a plant but who can help a country run the system safely and affordably for two decades.

Europe has ways to help close this gap, and it should consider them part of its energy policy. The EU’s diplomatic service points to DARYA and Erasmus+ as ways to support education, training, and connections for young people in Central Asia. In Kazakhstan, EU project notes say Erasmus+ offered over 3,300 short-term scholarships for Kazakh students and staff to study or train in Europe, and over 1,500 for Europeans to study in Kazakhstan. The same document notes a €76 million Erasmus+ budget for Central Asia for 2021–2027. These numbers are not just good stories; they represent growth for regulators, grid engineers, and project teams who can write better bids and manage complex constructions. They can also establish research labs in colleges that train technicians quickly.

China is also building human connections along with trade. A Chinese state news report mentions growing interest in learning Chinese in Central Asia, linked to cultural centers and Confucius Institutes. A regional research note counts 13 Confucius Institutes across Central Asia, as well as Confucius classrooms. This could be seen as simply building influence, but it also reduces everyday problems when instructions, software, and vendor support are in Chinese. The best response is balance, not worry. Central Asian ministries can invest in multilingual technical training that aligns with the equipment's source while still developing global skills. They can also create a regional skills program that recognizes short-term certificates across borders, so skilled workers can move to projects and improve standards through competition.

Some may argue that education develops too slowly for an urgent change. The response is that not all learning requires a four-year degree. The quickest improvements come from short courses, on-site learning, and clear tests. Micro-credentials for solar installation, high-voltage safety, SCADA use, and environmental rules can be established in months. If licenses and public bids require them, they spread quickly. Managers can develop training partnerships with project developers and share completion and job-placement rates, ensuring funding is based on results. Policymakers can also include training in agreements: local apprenticeships, certified safety teams, and maintenance knowledge as important criteria, not afterthoughts. This is how the shift to clean energy in Central Asia remains neutral amid competing supporters.

China’s leadership in manufacturing is not a reason to abandon choice; it is a sign of where influence currently lies. If Central Asia treats skills as an afterthought, it will import control along with equipment. If it treats skills as infrastructure, it can secure the best deal from each partner while retaining control. The message is to make the move to clean energy in Central Asia as much about skills as it is about energy. Educators should teach practical grid skills and contract knowledge, not just climate statements. Managers should create quick training programs with industry and track job results. Policymakers should include training, open data, and local services in every bid, regardless of where the funding comes from. Then, the 80% supply chain fact will not determine the future; instead, the region’s own abilities will.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ACWA Power. (2024, May 8). ACWA Power signs USD 4.85 billion deal for Central Asia’s largest wind farm. Press release.

Associated Press. (2025, April 4). EU leaders hold their first summit with Central Asian states. Associated Press.

DGAP (German Council on Foreign Relations). (2025, May 14). Rethinking EU strategy in Central Asia.

Eurasian Research Institute. (2020, December 21). Soft power in Central Asia: Turkey vs. Russia vs. China.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. (2024, January 25). EBRD posts strong operational results in Central Asia in 2023.

European Commission. (2022, November 8). EU and Kazakhstan sign Memorandum of Understanding on a strategic partnership on sustainable raw materials, batteries and renewable hydrogen value chains.

European External Action Service. (2023, October 19). EU projects with Kazakhstan.

European External Action Service. (2025, February 18). Investing in People: EU support for education and skills development in Central Asia.

European Union, Directorate-General for Energy. (n.d.). EU–Central Asia energy cooperation.

International Energy Agency. (2022). Solar PV global supply chains: Executive summary.

International Renewable Energy Agency. (n.d.). Kazakhstan: Renewable energy statistics profile.

International Renewable Energy Agency. (n.d.). Uzbekistan: Renewable energy statistics profile.

Masdar. (2024, November 13). Masdar signs agreement to develop 1GW Mingbulak Wind Farm in Uzbekistan. Press release.

Xinhua. (2025, June 15). Xi’s upcoming visit to advance China–Central Asia community with shared future. Xinhua.

Comment