Narrative Literacy Is the New Civic Basic

Input

Modified

Stories outlast statistics, and feeds reward that Viral politics runs on heroes, villains, and anger Teach narrative literacy, and push for cleaner platform data

A study found that the impact of a statistic on belief decreased by 73% after just one day, whereas the effect of a story decreased by only 32%. This difference should influence how education approaches public discourse. For many students, the public square is now a feed rather than a traditional meeting place. In 2025, 44% of 18–24-year-olds reported that social media is their primary news source, and video-based news consumption reached 65% . If stories are more memorable than numbers, then the feed does more than just transmit information. It shapes what people remember when they vote, debate, or decide who they trust. Narrative literacy—the skill to identify the story frame within a post and maintain factual awareness long enough to evaluate it—is a crucial missing element.

Educational institutions have tried to address misinformation through data literacy, media literacy, and an emphasis on critical thinking. While these efforts are valuable, they often assume that the main problem is poor data, which is countered by good data. Feeds, instead, favor content built around character and drama. Someone is presented as a hero, villain, or victim, and the narrative appeals to beliefs, ego, and emotions. Numbers might be present, but they often serve as supporting details rather than actual evidence and spread very rapidly. Narrative literacy is not a replacement for data literacy. It makes data relevant and applicable when a headline feels personal, when a meme is provocative, and when comments transform a statement into a group identity marker.

It is helpful to distinguish between two often-combined aspects. One is the format of information: words, stories, or statistics. The other is the method of provocation: how a message links to a person’s identity and emotions to encourage sharing. Classrooms can teach students to read charts, but they may still fail if a compelling villain story has already defined the situation. However, the same chart could be helpful if used to question the narrative at the right time. This is not just a theoretical issue. News surveys suggest that audiences are overwhelmed and easily distracted, making simplistic narratives more appealing. In Germany’s 2024 digital news survey, 41% said they felt overwhelmed by the volume of news, with that figure rising to 51% among 18–24-year-olds. Social media was the leading online source, with a weekly reach of 34%. Narrative literacy is a policy approach suited to this environment, teaching students to recognize the underlying narrative quickly and to ask a question that can curb its spread: what would have to be true for this story to be false?

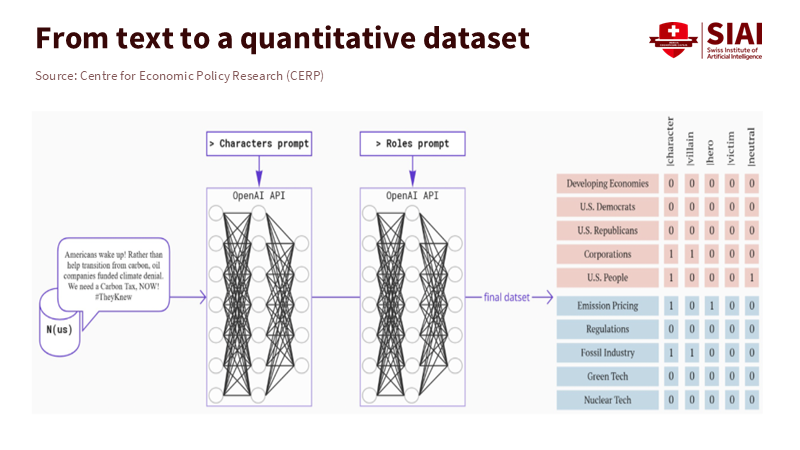

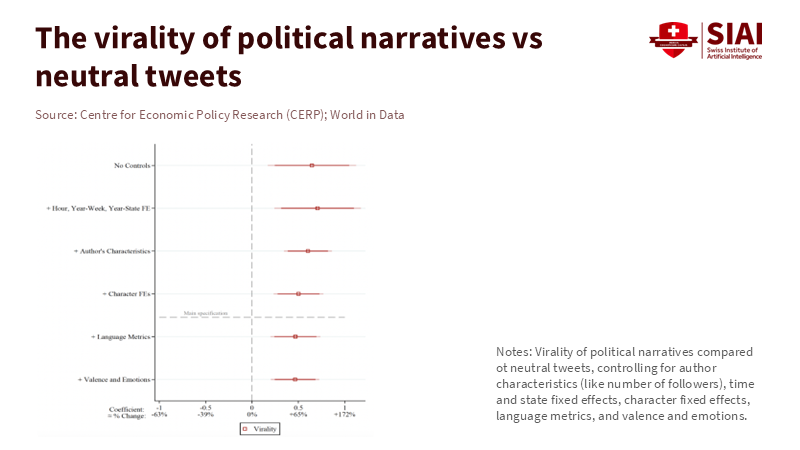

Narrative literacy and the virality gap

Narrative literacy begins with an important observation about attention spans: drama reduces subjects into short, emotional moments. A villain makes an issue seem personal and very important. A hero offers a sense of identity and moral approval. A victim indicates risk and calls for protection. These roles do more than simply decorate a message. They can suggest how widely it spreads. A 2025 study of U.S. political posts categorized characters by role in the drama and found that villain narratives correlated with a much greater increase in retweets than neutral posts (around +170%), and hero narratives also boosted retweets (around +55%). This is relevant to schools because it shows that presenting only the facts is often not enough. By the time a chart is shared, the story has given the audience its characters, motivations, and targets. Narrative literacy teaches students to first identify the characters, because this shapes how they view any evidence.

Platforms then promote the emotional signals they can quickly measure, and these are often linked to anger and blaming of outside groups. In one study comparing an engagement-based timeline with a chronological one, the engagement-based timeline showed posts that expressed more anger and greater animosity toward outside groups. 62% of political posts chosen by the engagement-based algorithm expressed anger, compared to 52% in the chronological feed, and hostility toward outside groups rose from 38% to 46%. A 2025 replication and review of studies on moral contagion found that each additional moral-emotional word in a post was associated with about 13% more sharing on average. Narrative literacy is essential here because it teaches students to recognize when a message is intended to stir emotions rather than inform. It changed this, making me angry, into an initial analytical observation rather than a final decision.

Narrative literacy in a low-numeracy world

The impact of simple narratives is related to the public's grasp of numerical information. Across OECD countries in PISA 2022, 31% of 15-year-olds performed below baseline Level 2 in mathematics. These students are not necessarily bad at math, but often struggle with tasks in political statistics, such as comparing rates, interpreting scale changes, or relating trends to support a claim. Adults have similar difficulties. Across OECD countries in the latest Survey of Adult Skills, 25% of adults scored at Level 1 or below in numeracy, while only 14% reached the top levels. When a significant portion of the public struggles with ratios and baselines, a number without context is unclear. It becomes a blank space that the story can fill.

If statistics fade from memory quicker than stories, then people with weaker math skills are at a disadvantage. Story cues are easier to process initially. The numbers that might correct the story are less likely to be recalled later. This explains why a vivid example can be more persuasive than a careful average, even among educated people. It also highlights the importance of video news. Video excels at showing faces, tone, and conflict, but is weaker with uncertainty and scale. Narrative literacy provides students with a means to address this trend. They can question what the story omits. They can also practice changing a number into a comparison that is understandable and memorable.

Consider how quickly a number can be turned into a memorable idea. A post claims that spending doubled or crime rose 200%, and the antagonist is clear. Narrative literacy involves asking for the missing details before the emotion becomes a belief. Doubling from what starting point? Over what time frame? Per person, household, or incident? A rate can increase because the numerator increased, because the denominator decreased, or because the definition changed. Students do not need advanced statistics to see these misleading claims. They need to develop the habit of turning a statement into a multipart question. This also allows them to treat stories more fairly. A single story can be true, but still misleading if presented as representing an overall trend. Narrative literacy allows students to feel empathy and be skeptical, something that is often discouraged.

Teaching narrative literacy as a core school skill

Narrative literacy can be integrated into schools without creating biased environments. The goal is a consistent method used across different subjects, similar to close reading or lab safety. Students learn to identify the characters, the claim, and the causal link; who is presented as the hero, villain, and victim; what is claimed, and what is suggested but not stated. Then, they make a simple evaluation: what would convince a reasonable person that the claim is false? Only then do students use numbers, with a clear purpose: to test the story, not just reinforce it. In history, students can chart the roles of characters in speeches and compare them with source material. In science, they can turn viral claims into testable questions and determine which data would disprove them. In math, they can practice the three steps that are often hidden: define the baseline, select the correct denominator, and state the degree of uncertainty. The result is not distrust, but informed curiosity.

Some might argue that narrative literacy will bias schools politically, or that teachers lack the time to implement another program. Both concerns need to be addressed. First, narrative literacy is a skill, not a fixed set of views. It teaches students to examine narratives rather than accept them at face value. Teachers do not need to say which side is correct; they only need to guide how claims are tested. Second, focused skill-building can have long-term effects. A 2025 study that compared fact-checking with a short media literacy activity discovered that fact checks mainly changed opinions about the specific claim they addressed, while media literacy improved the ability to determine truth more generally, both immediately and almost two weeks later. That finding supports a school plan focused on building habits rather than endless debunking. It also reflects the fact that many people use social media for updates and are concerned about misinformation. Narrative literacy is not an additional burden; it is essential for protecting sound reasoning.

Narrative literacy needs cleaner platform data

Narrative literacy should also change how policymakers view studies on what goes viral and what influences people. Much research depends on incomplete, hard-to-reproduce, or policy-skewed platform data. Even basic data can be unreliable. In late 2025, a central platform introduced account country labels and quickly faced complaints about inaccuracies. The platform removed some location fields after acknowledging that the data was not 100 percent accurate, especially for older accounts. The situation turned into its own viral drama, with users accusing people of being foreign agents based on questionable labels. This shows, in real time, what happens when a measurement is flawed: it can feed the very narratives it is meant to clarify. Education researchers and policymakers should not stop using measurement, but demand better documentation, more precise data, and more complete reporting of uncertainties.

A stronger approach is to combine classroom narrative literacy with policies that make the information environment easier to understand. UNESCO reports that 56% of internet users often use social media to stay informed, and that 85% of people are concerned about online misinformation. Given this scale, transparency is something the public needs, not a luxury for researchers. Policymakers can support narrative literacy by creating more straightforward guidelines for independent access to platform data, with privacy protections, and by requiring public logs when ranking systems or labeling features change. Education ministries and districts can also set standards for what they buy in educational technology and school communications: no defaults that favor engagement-first for public information, clear labeling of manipulated media, and evaluation methods that measure learning instead of clicks. This is not about censoring political views. It is about setting up conditions where people can see when a story is designed to provoke strong reactions, and where educators can teach with evidence that is not compromised by hidden platform changes.

The statistic about memory at the beginning should be seen as both a warning and an opportunity. If the convincing power of statistics fades so quickly, then simply using more charts will not improve civic learning. But because stories remain in memory longer, education can make use of that, rather than fight it. Narrative literacy teaches students to pause when a narrative grips them. It provides them with language to describe how roles such as hero, villain, and victim affect what they believe and how their egos and emotions are involved. It also gives them methods to remember numbers long enough to ask what they really mean, compared to what, and for whom. Teachers can instruct students in this method. Administrators can set aside time for it and show how it is used in school communications. Policymakers can fund it and require data practices that make it teachable. The aim is focused and pressing: a generation that can enjoy stories, feel emotions, and still remember the facts later.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Berger, L. M., Kerkhof, A., Mindl, F., & Münster, J. (2025). Debunking “fake news” on social media: Immediate and short-term effects of fact-checking and media literacy interventions. Journal of Public Economics, 235, 105345.

Brady, W. J., Rathje, S., Globig, L. K., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2025). Estimating the effect size of moral contagion in online networks: A pre-registered replication and meta-analysis. PNAS Nexus, 4(11), pgaf327.

Gehring, K., & Grigoletto, A. (2025). Virality: What makes narratives go viral, and does it matter? CESifo Working Paper No. 12064.

Graeber, T., Roth, C., & Zimmermann, F. (2024). Stories, statistics, and memory. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 139(4), 2181–2225.

Knight First Amendment Institute. (2023). Engagement, user satisfaction, and the amplification of divisive content on social media. Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University.

Leibniz Institute for Media Research | Hans-Bredow-Institut. (2024). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2024: Findings for Germany.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024). Adult numeracy skills (PIAAC Cycle 2). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

O’Brien, T. (2025, November 23). X’s messy “About This Account” rollout has caused utter chaos. The Verge.

UNESCO. (2023). Media and information literacy: Facts and figures (UNESCO/IPSOS, 2023). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

UNESCO. (2024). Media and information literacy: Facts and figures. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Voutsina, K. (2025, June 17). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2025: A media ecosystem in flux. iMEdD Lab.

Comment