Security Industrial Policy Is Now Education Policy

Input

Modified

Security industrial policy now shapes what schools can access and teach Education must build resilience without shutting down openness Strategy will fail without skills pipelines and smart campus rules

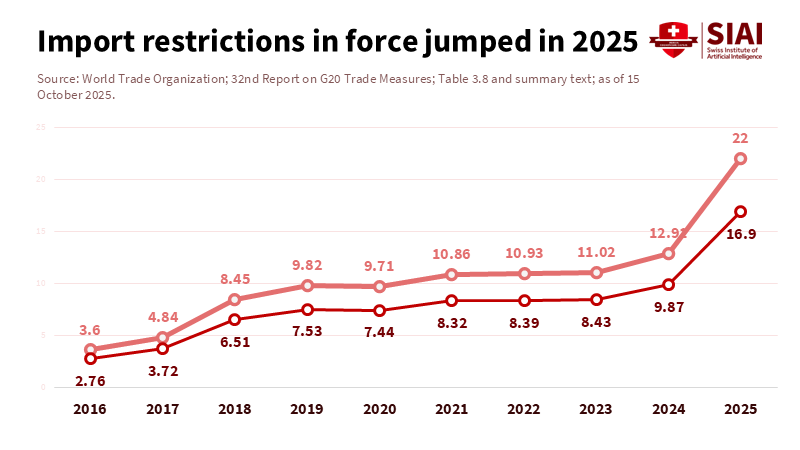

By October 15, 2025, import restrictions across the G20 affected roughly USD 4.015 trillion in trade, accounting for 22% of G20 imports. A WTO report places this figure at 16.9% of global imports, indicating a stable shift, rather than a temporary disruption. With policies impacting a large portion of imports into the world’s biggest markets, access is no longer guaranteed. Industrial policy driven by security concerns dictates the flow of resources, the purchase of equipment, and the exchange of ideas. Educational institutions are experiencing this shift. Cloud-based education, lab equipment, or collaborations with foreign institutions are now subject to supply chain competition. Whether acknowledged or not, education policy is becoming more intertwined with strategic considerations.

While industrial policy was once promoted as a path to development, promising more output and job growth, today it's framed as security industrial policy, emphasizing the avoidance of dependence over pure growth. Sectors crucial to power also influence education. Chips, batteries, AI, satellites, and cloud platforms affect both the economy and the classroom. Teaching and research are adapting to restricted access to these resources. This also happens when supplies are limited or platforms are controlled. This is not merely a matter of trade, but a fundamental systemic issue for education. The challenge is to promote expertise without turning schools into instruments of competition, while maintaining openness in areas where it yields benefits. The definition of a safe partnership is changing, including who is allowed to share resources.

Security industrial policy is changing the purpose of education

The impact of security industrial policy is apparent in semiconductors, as computer chips are essential. In the U.S., the CHIPS and Science Act allocated significant funding to boost domestic semiconductor manufacturing and support related programs. This initiative is linked to research and workforce development to ensure the plants can operate with skilled personnel. Europe is doing something similar. The EU’s Chips Act involves substantial public investment, along with policy-driven public and private investment projected through 2030. For educators, the message is that governments consider the development of skilled workers as essential infrastructure, not just a benefit to society.

Security industrial policy also limits access to advanced supplies. In early 2025, the U.S. Commerce Department imposed tighter restrictions on advanced computing chips. The OECD reports a sharp increase in export controls on industrial materials between 2009 and 2023, with many new restrictions in 2023. Demand for vital materials such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and rare earths is rising, complicating access to labs and research planning. Supply risk is now central to education’s operating environment.

Security industrial policy transforms universities into strategic assets

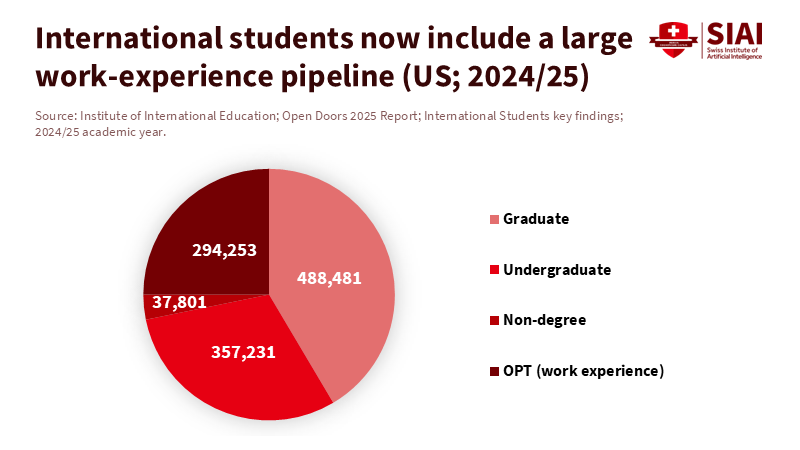

Under the security industrial policy, universities are becoming strategic assets rather than neutral sources of talent. They produce skilled workers who grow domestic production. They make knowledge into products. Governments are tightening regulations on work and research collaborations involving sensitive topics. However, international talent remains critical to universities. According to Open Doors data, U.S. higher education hosted many international students the previous year, with the most students coming from India and China. There was also a record number of participants in Optional Practical Training, highlighting the connection between study and work. A security industrial policy that views this as a threat risks damaging its own resources.

Funding can make problems worse. Data shows education rose the previous year, representing the fastest increase in years. International students support campus budgets and local economies. Estimates show international students contributed billions to the U.S. economy and supported domestic jobs during that time. These factors affect university funding, including labs and staff. Instead of advocating complete open access, it is better to develop clear guidelines, fair review processes, and compliance support. If done correctly, security industrial policy can help manage risk without reducing the talent pool that drives research.

What could this involve on campus? Universities can treat security industrial policy as a regular part of operations. Universities can assess which labs use specific equipment and which partnerships involve particular fields. They can develop rules that staff can follow, centralize oversight, and ensure projects move forward quickly. They can also protect crucial open research. Basic and social sciences have a lower risk. Keeping these channels open builds trust and improves quality. Universities should share strategies, as inconsistent regulations create vulnerabilities. If governments want more capacity, they should fund governance efforts, as they do for labs and education. If not, these tasks will take up faculty time and impact teaching.

Security industrial policy spreads through digital rules

Beyond factories and controls, security industrial policy also shapes platform power through regulations. The EU’s Digital Markets Act aims to ensure competition and fairness in digital markets. It seeks to regulate large digital platforms. The goal is competition, not privacy. When platform rules are rewritten, it affects who can grow. The EU has designated gatekeepers to show enforcement. This is a security-industrial policy implemented through regulation.

Education is highly impacted by digital policy. Schools procure learning platforms, cloud storage, and AI programs. Universities depend on systems and cloud solutions. When regulations change, what gatekeepers can do, education changes. Features are redesigned, data routes change, and compliance increases for campus IT. Administrators can treat digital procurement like resilience planning and develop diversification plans. Policymakers can adjust education rules with a digital strategy, avoiding forced changes and lock-in. If security-industrial policy shapes platforms, education needs to learn to negotiate with it.

Education needs boundaries in security industrial policy

Some might say that security industrial policy will lead to the militarisation of education. This is a valid concern, but it can be controlled. The data shows that inaction is not an option. Trade restrictions involve trillions of dollars of imports, meaning education will be involved, whether there is a plan or not. The question is whether to respond fearfully or with a design that allows for learning in a safe environment.

Design begins with clarity. Schools can teach students about security industrial policy as a real economic policy, with its limits and tests. Students can learn how to control change efforts. They can understand what “dual use” means. Schools can make governance simple for staff to follow, while researchers can keep working. Policymakers can invest in related fields. They can protect openness where it is safe, and fund research while keeping student pathways predictable. This can build skill, trust, and the universities that depend on the plan.

To reiterate, billions in trade were under measure. Education operates in this setting. Education leaders should respond with a system. Teach students how trade works and how to conduct research. Safeguard research that makes things more challenging to control, all while keeping cooperation where it is needed. Learning isn't meant to be a weapon.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Berger, L. M., Kerkhof, A., Mindl, F., & Münster, J. (2025). Debunking “fake news” on social media: Immediate and short-term effects of fact-checking and media literacy interventions. Journal of Public Economics, 235, 105345.

Brady, W. J., Rathje, S., Globig, L. K., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2025). Estimating the effect size of moral contagion in online networks: A pre-registered replication and meta-analysis. PNAS Nexus, 4(11), pgaf327.

Gehring, K., & Grigoletto, A. (2025). Virality: What makes narratives go viral, and does it matter? CESifo Working Paper No. 12064.

Graeber, T., Roth, C., & Zimmermann, F. (2024). Stories, statistics, and memory. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 139(4), 2181–2225.

Knight First Amendment Institute. (2023). Engagement, user satisfaction, and the amplification of divisive content on social media. Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University.

Leibniz Institute for Media Research | Hans-Bredow-Institut. (2024). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2024: Findings for Germany.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024). Adult numeracy skills (PIAAC Cycle 2). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

O’Brien, T. (2025, November 23). X’s messy “About This Account” rollout has caused utter chaos. The Verge.

UNESCO. (2023). Media and information literacy: Facts and figures (UNESCO/IPSOS, 2023). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

UNESCO. (2024). Media and information literacy: Facts and figures. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Voutsina, K. (2025, June 17). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2025: A media ecosystem in flux. iMEdD Lab.

Comment