When the Housing Wealth Effect Reaches the Classroom

Input

Modified

Housing wealth losses are squeezing education budgets Cuts hit “extras” first, widening gaps fast Schools need funding buffers and lower pressure

According to research, a 10% change in home values can predict a 1.6% change in spending in China’s biggest cities. This is based on observation of household spending over time (Mojon, Qiu, Wang, & Weber, 2025). This data shows what families will stop buying first when they feel less wealthy. The home wealth impact extends beyond shopping habits; it affects people's faith in the future, their plans, and their willingness to take on risk. When homes are the primary source of wealth, a prolonged price decline can cause people to put many aspects of their lives on hold. Families might hold off on improvements, reduce non-essential expenses, and save more to feel secure. Education, despite its importance, is often considered an optional expense. While basic schooling might be seen as essential, related costs like preschool, tutoring, materials, transportation, and willingness to pay for better options are not. If China is facing a long-term period of reduced housing wealth, education systems should consider this a serious challenge to learning, not just a minor issue.

The effect of housing wealth has reached school budgets

Education policies often assume that parents will always prioritize education. The housing wealth effect undermines this assumption by treating housing prices as a proxy for wealth. By 2025, many saw China’s real estate decline as hurting people's confidence. Some estimates suggest that about 70% of household wealth is tied to real estate. Research linking housing deals to payment data shows that housing makes up about 70% of urban families' total assets. The actual percentage varies by city, age, and level of debt, but the overall trend is clear: many families see falling home prices as a reduction in their life choices. This affects how they view education.

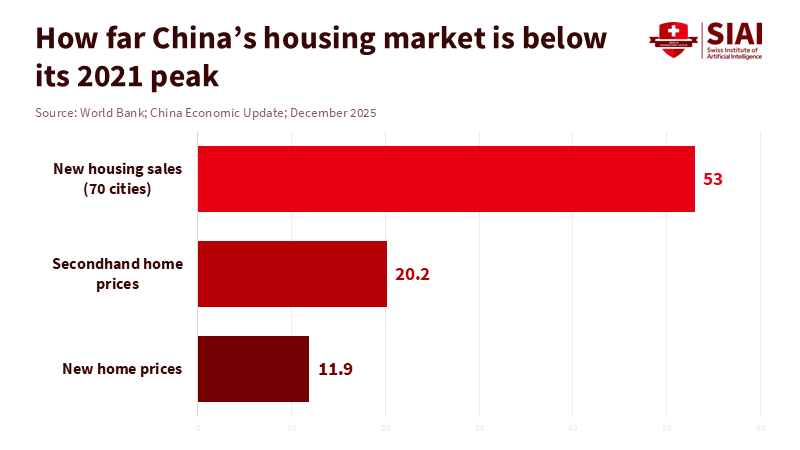

By the end of 2025, the real estate market was still unstable. Reuters reported that new home prices fell 0.5% from the previous month and 2.2% from the prior year, while real estate investment dropped 14.7% in the first ten months of 2025. A global report in December 2025 said that prices for new homes had fallen by 11.9% and for secondhand homes by 20.2% from the peak in July 2021. New home sales in 70 cities were 53% lower than the 2021 peak by October. These numbers are relevant to educators because they show a continuing decline in people's perceived wealth and a steady stream of bad news. In a housing wealth impact, this constant bad news is as important as the price levels themselves. Repeated price drops teach families to wait before spending, which is wise when buying a sofa but harmful when it comes to a child’s education.

Why does the housing wealth impact force families to make trade-offs about education?

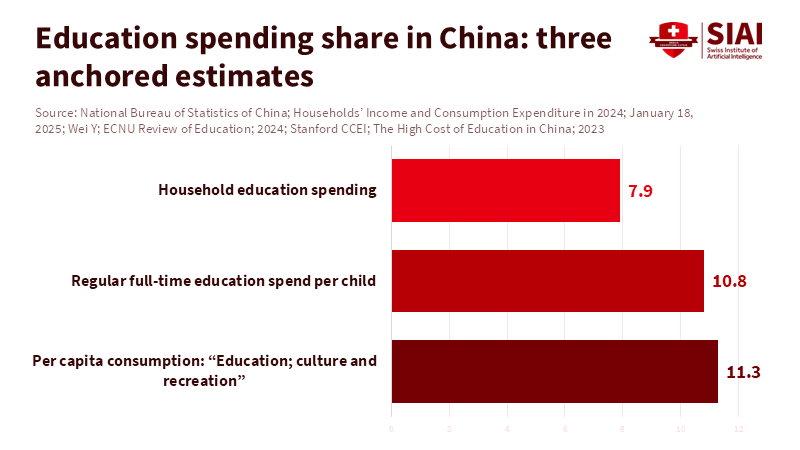

Education is often considered a priority, but it takes up a big part of a family’s budget. Statistics from 2024 show that people spent about 450 USD per person on education, culture, and recreation, which is 11.3% of their total spending. While this category includes more than just schooling, it shows that education-related expenses are large enough to cut back on. The impact of housing wealth does not mean families stop valuing education. It means they start prioritizing education expenses. They might keep paying basic fees, but they will likely cut back on quality extras. Schools will then notice changes that might seem confusing if the bigger economic situation is not taken into account: fewer students signing up for enrichment programs, more requests for discounts, more students traveling from cheaper neighborhoods, and a shift away from expensive programs. These small changes add up to a significant loss in learning.

Household data clarifies the scope of the problem. A study of national household surveys reports that families spend an average of 1,145 USD per child on regular full-time education, about 10.8% of their total spending. The estimated cost of education from preschool through a bachelor’s degree is about 32,800 USD. The same study says that in the 2018–2019 school year, 24.4% of elementary students and 15.5% of high school students received tutoring outside of school. Another report summarizing research using China Family Panel Studies data says that families spend about 7.9% of their yearly expenses on education and that lower-income families spend a substantial share of their income on education. These expenses become harder to handle when housing wealth declines. Families might continue to pay for exam-related costs, but they will cut back on broader activities that support learning, such as reading, the arts, and stress-reducing activities.

The impact of housing wealth on local government budgets also affects them. Even if national budgets are maintained, school quality is affected by local governments' financial health. When housing and construction slow down, local governments' finances tighten, and the job market weakens, especially for workers from other areas and for those in informal jobs, who have fewer protections. A global report from December 2025 linked cautious household spending to a weak job market and continued problems in the real estate sector. It also noted that local government finances were tighter due to weaker infrastructure and real estate activity. In the same period, spending contributed 2.7 percentage points to year-on-year growth in the third quarter of 2025, but the report emphasized that spending remained cautious, partly due to a low starting point. This situation is risky for schools. Families become more mindful, while local governments have less money to support them. Schools are then asked to do more with less, even when students need more help.

What Japan's long, slow recovery can teach China's schools

Japan’s period after its economic bubble burst is often called a "growth story," but it teaches us how long these periods can last. The impact of housing wealth is not always a crash followed by a quick recovery. It can be a long period of caution, in which families act as if their wealth is fragile and their future is uncertain. In this situation, parents look for safe choices. They save more, delay important choices, and protect their children’s futures as much as possible. This focus does not always create better skills in children. It can push families to favor things that seem like insurance—extra coaching, test strategies, and focusing on credentials—while overall demand for education remains weak. Slow shifts are harder for schools to deal with than fast ones because they change what is considered normal slowly and quietly, making those changes seem permanent.

China is not Japan, but these situations can have similar effects. A global report from December 2025 noted that home prices in China have fallen significantly relative to household income during the downturn, but that price-to-income ratios remain high compared to other Asian countries, suggesting prices could fall further. This is important because the impact of housing wealth depends on what people expect, not just current price levels. If families expect prices to fall further, they will cut back early and save as much as possible. While it is true that education should not be expected to fix the housing market, it is also true that housing prices can affect education and the quality of learning. This, in turn, affects long-term productivity and societal trust. It is also argued that private education spending is a choice, so a decline in it is not a public concern. However, many private education costs are related to access—transport, materials, and tutoring needed to compete for limited spots—not luxury items. These are the first costs to be cut when the housing wealth impact hits.

Policies that address the impact of housing wealth as a challenge to learning

Policies should address the impact on housing wealth as a challenge to learning and create ways to stabilize the situation. The first way is to provide targeted, temporary help for education costs most likely to be cut and necessary for fairness: preschool fees, transport, meals, and learning support. This does not mean giving money to all families. It is a way to prevent the housing wealth effect from widening achievement gaps. Household data show that education spending already takes up a large share of family budgets—about 10.8% of total household spending per child in one national survey and about 7.9% of yearly household spending in another analysis. When wealth decreases, families can only continue to pay by cutting the activities that make learning better and more secure. Public support should be designed to protect these activities, especially for low-income families and families who have moved from other areas.

The second way to stabilize the situation is to protect schools' budgets in areas where the impact of housing wealth is most substantial. A late-2025 analysis noted continued weakness in the real estate sector, cautious household spending, and tighter local government finances. This creates a situation in which basic services are gradually reduced. Education ministries can respond by making funding formulas more responsive to economic changes and more needs-based, so schools are not punished for drops in local revenue. The priority is to maintain basic quality: stable teacher pay, class sizes, support for students with special needs, and basic maintenance. If these things are reduced, wealthier families will buy alternatives, while poorer families will simply have to accept the loss. The impact of housing wealth can last for years. Short-term consumer vouchers do not protect learning. Stable school funding does.

The third way to stabilize the situation is to reduce the pressure that makes private spending seem necessary. The Stanford report connects high household education costs to a limited number of high-quality opportunities and strong demand for them. Housing wealth exacerbates the problem, as families have less money while the stakes remain high. Policies can reduce pressure by creating more credible pathways: improving the quality and reputation of vocational and applied programs, making it easier to move between programs, and reducing the role of paid coaching in admissions. At the school level, leaders can simplify fee structures and remove soft barriers, such as informal charges that exclude poorer students. Finally, systems should watch for signs of the housing wealth impact: missed payments, fewer students being driven to school, students leaving tutoring programs, and counseling referrals. The goal is to provide early support, not to monitor people's behavior. The biggest and most costly mistake in a slow downturn is to notice the problems too late.

A 10% change in house prices linked to a 1.6% change in spending is not just a market statistic. It is an early warning sign for schools. If families see falling home prices as a sign of less security, they will continue to cut back on education-related expenses, even if they keep paying for basic schooling. This pattern will not be uniform, and it will affect the students who already have the least support. Assessments from late 2025 continued to show weakness in the real estate market and the possibility of further price declines. Waiting for the real estate market to recover is not a good education strategy. The practical goal is to prevent the housing wealth impact from turning into a learning wealth impact. This means stabilizing school funding, protecting necessary household resources, and reducing the pressure that drives costly private solutions. If education is to remain a safety net, it must be funded and designed accordingly.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Gao, L., & Woo, R. (2025a, November 14). China’s October new home prices fall at fastest pace in a year. Reuters.

Gao, L., & Woo, R. (2025b, December 23). China’s “housing market stability” pledge keeps homeowners waiting for a rebound. Reuters.

Mojon, B., Qiu, Z., Wang, J., & Weber, P. (2025). Housing wealth effects in China (BIS Working Papers No. 1319). Bank for International Settlements.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2025, January 17). Households’ income and consumption expenditure in 2024. National Bureau of Statistics of China.

Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions. (2023). The high cost of education in China. Stanford University.

Wei, Y. (2024). Household expenditure on education in China: Key findings from the China Institute for Educational Finance Research-Household Surveys (CIEFR-HS). ECNU Review of Education, 7(3), 738–761.

World Bank. (2025). China economic update: December 2025. World Bank.