France’s Sovereign Debt Sustainability Test Runs Through Schools

Input

Modified

Rising interest costs make France’s sovereign debt sustainability a school budget problem Higher defence pressure tightens the squeeze on education Italy shows credible fiscal plans can restore sovereign debt sustainability without wrecking schools

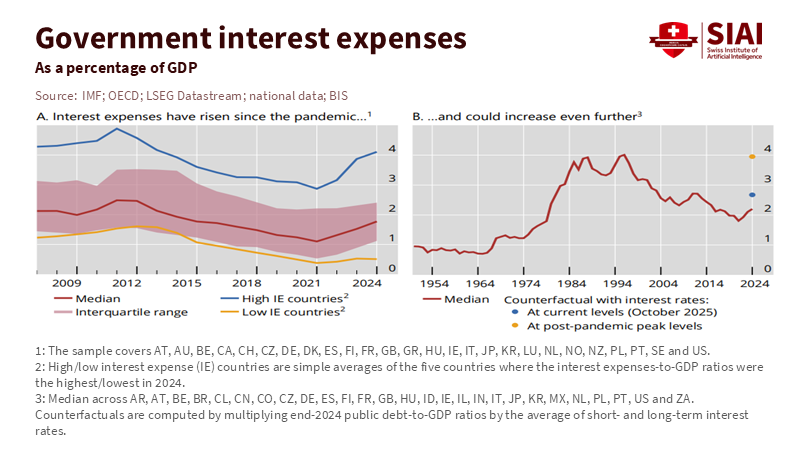

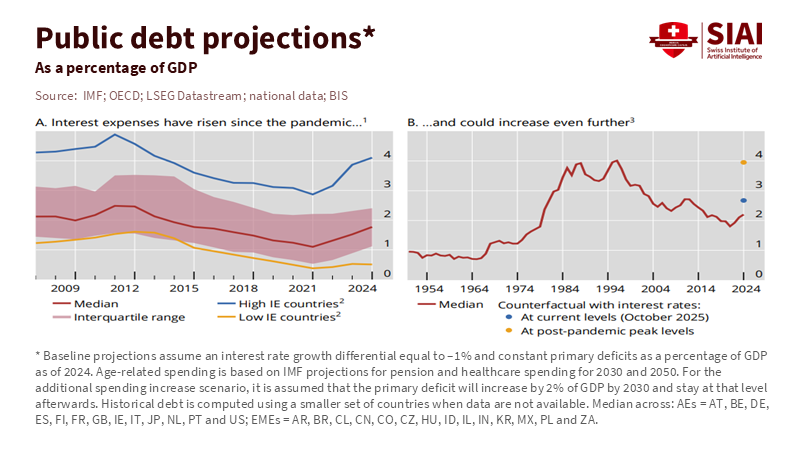

According to INSEE, France's public debt reached €3.482 trillion at the end of the third quarter of 2025, equivalent to 117.4% of the country's GDP. A debt of this kind extends beyond finance pages and influences daily budgets, as evidenced by delayed repairs, hiring freezes, and reduced student aid. The pressure is already evident in the interest payments. The Banque de France stated that the central government's debt charges grew from almost €30 billion in 2020 to €53 billion in 2023 as interest rates rose. This shift shows the basic calculation of sovereign debt and how it works in practice. A country can manage large programs when borrowing is inexpensive, but these programs may become too costly once interest becomes the fastest-growing expense. At that point, declines in education spending are made quietly. The situation is getting tougher as security costs rise. Reuters reported at the 2025 Hague summit that a NATO target was discussed, centered on 3.5% of GDP for core defense and 1.5% for wider security investment. Whether countries reach that level quickly or slowly, the trend is evident in Western Europe. At the same time, INSEE reports that France's general government deficit was €169.6 billion in 2024, which is 5.8% of GDP. This combination of high debt, a high deficit, rising interest rates, and greater defense spending expectations makes sovereign debt a greater problem. In an education system, this situation requires decisions about what is protected, what is rationed, and what is postponed. Sovereign debt is, therefore, a debate about learning policy.

Sovereign debt is determined by the learning system

Education seems protected by its large size and visibility, yet it is easily affected by quiet cuts. Most expenses are related to people. A system can save money by not replacing retirees, reducing support roles, postponing training, or delaying wage increases. These actions might not be evident on a budget chart, but classrooms notice quickly. OECD's Education at a Glance 2025 reports that France spends 5.4% of its GDP on education from primary to tertiary levels, above the OECD average of 4.7%. While this shows commitment, it also indicates exposure. Sovereign debt tests this exposure. When a country spends heavily on education and faces rising debt service, it must decide whether the system can maintain quality with limited resources. Sovereign debt, therefore, tests whether learning can be protected when budgets tighten.

Learning results emphasize what is at stake. OECD's PISA 2022 reported a drop in the OECD average compared to 2018: mathematics fell by almost 15 points, and reading by about 10 points. These declines create a growth problem because growth is what pays the interest on the debt. Fiscal tightening that harms early literacy, teacher supply, or the quality of apprenticeships can save money now, but may create problems by lowering productivity and revenues. It can also widen gaps. When public support declines, wealthy families can buy help while poor families cannot. That will worsen inequality, and distrust grows, blocking change. France cannot allow that to happen. The education system helps make fiscal improvements socially acceptable.

France uses education as the adjustment margin

Figures show persistence. INSEE estimates the 2024 deficit at 5.8% of GDP, down from 5.4% in 2023, with spending at 57.1% of GDP. During this time, the debt ratio continued to rise, and INSEE's quarterly release puts Maastricht debt at 117.4% of GDP in Q3 2025. The IMF's 2025 France Article IV statement calls for bringing the deficit below 3% of GDP by 2029 and for a strong plan. France is at risk, and sovereign debt will be a factor. A believable deficit path allows the state to plan, while a weak path causes it to make sudden changes. This is a concern for education because a poorly designed deficit plan often leads to short-term cuts when pressure rises. Education has elements that can be quietly cut: substitute coverage, counselor availability, special-needs support, maintenance, and curriculum time for basic skills. Sovereign debt will depend on whether France can fix its budget without cutting these things.

Even when ministers say education is protected, that protection can fail. A flat budget during inflation is a cut, and a stable staffing plan when salaries are low is also a cut. OECD's 2025 report for France says that spending per primary student is 13% below the OECD average, even before new constraints are taken into account. This detail is essential because primary education either prevents later costs or locks them in. When choices are made, the option that is expensive in the short run is often the best choice: stable teachers, smaller gaps, and support for struggling readers. For administrators, this is budget planning as much as teaching. Multi-year workforce planning, energy and maintenance upgrades that cut running costs, and purchasing that reduces digital churn all add strength.

Budget issues add risk because investment stops first. In December 2025, France passed an emergency law to keep the state operating into early 2026 while budget talks stalled, according to Reuters and the Financial Times. Reuters said a similar measure previously cost about €12 billion and prevents new investment while it is in force. Even when salaries are paid, halting investment delays school renovation plans, slows digital projects, and slows growth. It makes improvements difficult later, usually at a higher cost, leading to more debt. Interest costs rise, investment falls, and growth weakens. Then, sovereign debt becomes difficult to manage. For leaders, the lesson is to protect what improves learning, because the stop-start pattern is a hidden cut.

Defense raises the stakes for sovereign debt

Defense spending is rising across Europe. SIPRI's 2025 fact sheet on spending reports that it increased 17% in 2024 to $693 billion, the highest level since the end of the Cold War. The same publication says European NATO members spent $454 billion in 2024, while total NATO spending reached $1.506 trillion. These facts change sovereign debt because more defense tends to be tied to deterrence, alliances, and industrial planning. The new NATO measure described by Reuters points to 3.5% of GDP for core defense and 1.5% for wider security investment. If budgets cannot grow fast enough, something else must change. In practice, that something is often education, training, and research. That is how sovereign debt can be hurt by security choices.

Some say that defense spending can boost growth by fostering innovation and creating jobs. Sometimes that is true, but defense-led growth puts gains in a few places and does not replace general skills. Modern deterrence depends on expertise, data analysis, logistics, maintenance, energy systems, and manufacturing. Those abilities are built in schools. A defense surge that drains the education system is bad. It also raises questions. When citizens see higher taxes or lower services with higher defense budgets, they want to know what they are getting in return. A good answer depends on whether the state can still provide education and opportunity. That is why education leaders should watch sovereign debt as part of planning. It is also why policymakers should link defense to skills, not to quiet cuts in the learning system.

Italy shows what can happen if schools are not protected

Italy provides a contrast for the debt debate. Eurostat reports that Italy's debt was 138.3% of GDP at the end of Q2 2025, while France's was 115.8%. Yet markets have been treating Italy as a managed risk. Reporting in the Financial Times described Italy's and Spain's spreads over Germany falling to their lowest levels in about 16 years, with Italy around 0.7 points and Spain below 0.5. That did not happen because the debt vanished. It happened because investors saw a steadier direction and fewer issues. Sovereign debt depends on politics and trust. France's problem is that its policy feels weak.

France's situation is obvious. Debt is lower than Italy's, yet risk feels higher because policy looks stuck. When parliaments cannot pass a budget, the state operates under emergency laws and cannot invest. Markets notice, and so do schools. The lesson from Italy is that a credible path can buy time and lower borrowing costs. France needs that cost to fall because defense is rising, and interest payments are large. Measures should try to remove surprise. They should link budgets to a published plan and require an assessment of the impact on education. New defense investments should go toward joint projects to avoid duplication. Policy commentary has warned that France's debt could lead to early social cuts that would hurt education. None of this is easy, but sovereign debt was never going to be easy once debt passed 100% of GDP.

France can change direction, but minor changes are not likely to be enough. Sovereign debt now requires measures that stabilize the system, not promises that fail. The core should be a legislated fiscal plan that lasts, along with an education protection rule that targets quality. This is sovereign debt with a learning focus. Protection should focus on the things that raise learning and growth: early literacy and numeracy, teacher recruitment, and training for defense, energy, and digital needs. For educators, this means pushing for stability, not short projects that vanish with the next budget. For administrators, it means publishing what cuts do to class time. For policymakers, it means treating education as a means to achieve fiscal improvements. The €3.482 trillion debt is a plan. Each year of delay makes the adjustment difficult, and the classroom suffers.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Banque de France. (2024). The debt interest bill: why it rises when rates rise (public explainer on central government debt charges).

Bank for International Settlements. (2025, November 27). Hernández de Cos, P. Fiscal threats in a changing global financial system (speech).

Economy.ac. (2025, October 17). Brennan, A. IMF Warns of Global Debt Spiral as U.S. and Europe Struggle Under Fiscal Strain.

Economy.ac. (2025, October 21). Griffin, O. France Hit by Triple Credit Downgrade, Default Risk Looms Amid Fiscal Paralysis.

Economy.ac. (2025, November 24). Brennan, A. “Europe Must Face Russia on Its Own” — U.S. Pressure Drives Defense Spending Surge, Raising Fears of a Deepening Fiscal Crisis.

Eurostat. (2025, October 21). Government debt at 88.2% of GDP in euro area (Q2 2025 debt release).

International Monetary Fund. (2025). France: 2025 Article IV Consultation—Concluding Statement / Staff Report materials (deficit path and credibility).

INSEE. (2025). General government debt (Maastricht definition), Q3 2025 (debt level and debt-to-GDP).

INSEE. (2025). General government accounts: deficit 2024 (deficit and spending shares).

NATO. (2025, June 25). The Hague Summit Declaration (5% structure: 3.5% core; 1.5% security investment).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024). PISA 2022 Results (learning declines vs 2018).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). Education at a Glance 2025: France country note (education spending share; per-student detail).

Reuters. (2025, June 25). What is NATO’s new 5% defence spending target?

Reuters. (2025, December 23). France passes budget rollover law; investment freeze and prior stopgap costs (budget rollover detail).

SIPRI. (2025). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024 (Europe and NATO spending totals).

Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence Review. (2025, December 14). O’Neill, D. Italy’s Fiscal Rehab, France’s Drift, and Why US Fiscal Sustainability Now Shapes Education.

The Financial Times. (2025, December 28). Periphery spreads and market pricing of Italy/Spain risk (news report summary).

Comment