Beyond Deepfake Image Rights: Building Real Protection in a Zero-Cost Copy World

Published

Modified

Deepfake image rights alone cannot stop fast, zero-cost copying of abusive content We need layered protection that combines law, platform duties, and strong school-level responses Education systems must train students and staff, act quickly on reports, and treat synthetic abuse as a shared responsibility

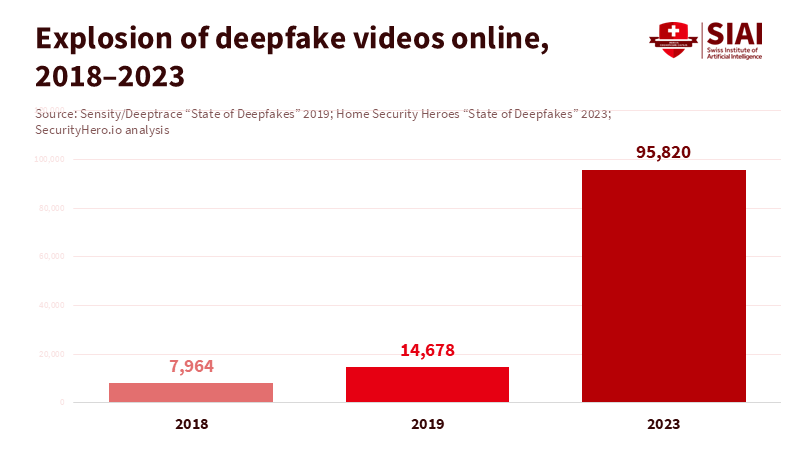

Generative AI has made image abuse a widespread issue. A 2024 analysis of nearly 15,000 deepfake videos found that 96 percent were non-consensual intimate content, particularly targeting women. In 2023, there were about 95,820 deepfake videos indexed online, with 98 percent being pornographic and mostly showing women and girls. Most of these are pornographic materials that the victims never agreed to create or share. At the same time, the cost of copying these files is nearly zero. Once a clip is uploaded, it can be mirrored, edited, and reposted across platforms in minutes. In response, lawmakers are swiftly working to strengthen protections against deepfakes, introducing new criminal offenses and proposing that each person’s face and voice be treated as intellectual property. Yet a crucial question remains: can rights that depend on slow, individual enforcement really protect people in schools and universities from abuse that spreads in seconds?

Deepfake Image Rights in a Zero-Cost Copy World

Discussions about the rights to deepfake images often begin with a hopeful idea. If everyone owns their likeness, victims gain a legal tool to demand removal, fines, or damages. Granting individuals copyright-like control over their faces, voices, and bodies seems empowering. It aligns with existing ideas in privacy, data protection, and intellectual property law, delivering a straightforward message to anxious parents and educators: your students' faces will belong to them, not to machines. In countries with strong legal compliance and resources, this model might deter some abuse and simplify negotiations with platforms. Denmark’s initiative to grant copyright over one’s likeness and to fine platforms that do not remove deepfakes exemplifies this approach.

The challenge lies in scale and speed. Non-consensual deepfake pornography already dominates the landscape. A study of 14,678 deepfake videos found that 96 percent involved intimate content created without consent. A 2025 survey on synthetic media use concluded that non-consensual pornography represents the vast majority of deepfake videos online. For targeted individuals, the initial leak is often just the beginning. Copies circulate rapidly between sites, countries, and languages, faster than any legal notice can reach them. They are remixed, cut into shorter clips, and reposted under new titles. Granting victims greater rights over deepfake images does not reduce copying; it merely adds more paperwork for them to deal with after the fact, usually at their own cost, with no guarantee that overseas hosts or anonymous users will comply.

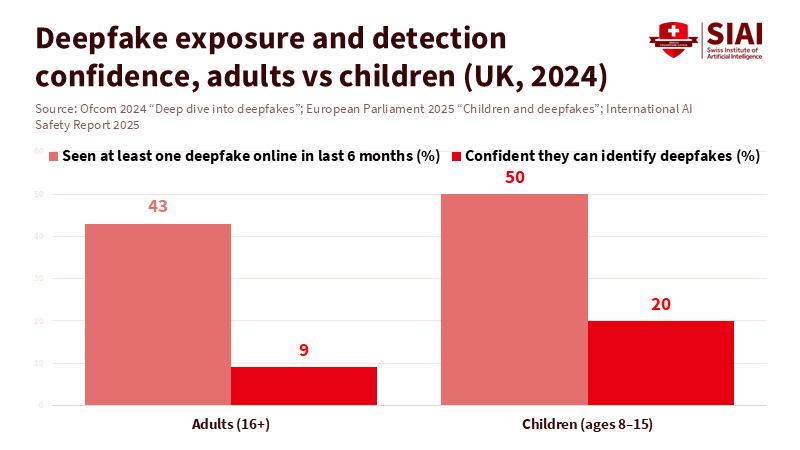

The impact on young people is especially concerning. Research for the European Parliament shows that half of children aged 8 to 15 in the United Kingdom have seen at least one deepfake in the last six months, with a significant portion of synthetic sexual content involving minors. A separate police-commissioned survey in 2025 found that about a quarter of adults felt neutral or unconcerned about creating and sharing non-consensual sexual deepfakes, with 7 percent admitting to being targeted. Only half of those victims ever reported the abuse. For a teenager who sees a fake explicit video of themselves spreading through their school overnight, the promise of future compensation will likely seem hollow. Deepfake image rights do not address the shame, fear, and social isolation that follow, nor do they restore trust in institutions that failed to act promptly.

Why Deepfake Image Rights Break Down in Practice

In theory, deepfake image rights empower victims. In practice, they shift the burden of responsibility. Someone who finds a sexualized deepfake must first recognize the abuse, gather evidence, seek legal help, and start a case that could take months or years to resolve. Meanwhile, the clip can be shared on anonymous forums, in private chats, and through overseas hosting services. Reports from law enforcement agencies, including the FBI in 2023, indicate a sharp rise in sextortion cases using AI-generated nudes created from innocent social media photos or video chats. Victims face threats of exposure unless they pay, yet even when police intervene, images already shared often remain online—rights based on individual enforcement lag behind automated, targeted, and global harms.

The emerging patchwork of laws highlights this gap. Denmark is working to give individuals copyright-like control over their images and voices, with penalties for platforms that fail to remove deepfakes. Spain plans heavy fines for companies that fail to label AI-generated content, following the European Union's broader requirement to mark synthetic audio, images, and video clearly. The 2025 Take It Down Act in the United States criminalizes non-consensual intimate deepfakes and requires major platforms to remove reported content within 48 hours and prevent duplicates from appearing again. The United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act makes sharing non-consensual deepfake pornography an offense. It is being bolstered by plans to criminalize its creation. On paper, victims now have more legal protection than ever before.

However, these gains are uneven and fragile. Many low- and middle-income countries lack specific deepfake regulations and have limited capacity to enforce existing cybercrime laws. Even where offenses exist, policing is often slow, under-resourced, and insufficiently sensitive to gender-based digital violence. A 2024 survey by researchers in the United Kingdom found that while about 90 percent of adults are concerned about deepfakes, around 8 percent admit to having created them. An international study of synthetic intimate imagery suggests that about 2.2 percent of respondents have been targeted and 1.8 percent have participated in production or sharing. The gap between concern and behavior indicates that social norms are still developing. Legal rights without swift, collective enforcement risk becoming a luxury for those who can afford legal representation in wealthy democracies, rather than a baseline for school and university safety worldwide.

The legal blind spots also show up in countries with major commercial pornography industries. Japan’s adult video sector is estimated to produce thousands of titles each month, generating tens of billions of yen in revenue. However, deepfake pornography targeting actresses, idols, and everyday women has only recently led to arrests for creating AI-generated obscene images. Regional legal scholars note that non-consensual deepfake creation often falls into grey areas, with no precise commercial distribution, making remedies slow and complicated. When deepfake abuse exploits popular, legal adult content markets, the harm can be dismissed as "just another clip." Deepfake image rights may appear robust in theory. Still, without quick investigative pathways and strong platform responsibilities, they rarely provide timely relief.

From Deepfake Image Rights to Layered Protection in Education

If rights to deepfake images aren't enough, what would proper protection look like, especially in educational settings? The first step is to consider deepfakes as an infrastructure issue, not just a speech or copyright concern. Technical standards are essential. Content authenticity frameworks that embed secure metadata at the point of capture can help verify genuine material and flag manipulated media before it spreads. Transparency rules, such as those requiring labeling of AI-generated images and videos, can be strengthened by requiring platforms to automatically apply visible markers rather than relying on users to declare them. National laws that already demand quick removal of intimate deepfakes, penalties for repeated non-compliance, and risk assessments for online harms can be aligned. This way, companies face clear, consistent responsibilities across different jurisdictions, rather than a confusing system that they can exploit.

Education systems can use this legal foundation to create a layered response. At the curriculum level, media literacy must go beyond general warnings about "fake news" and include practical lessons on synthetic media and deepfake image rights. Students should understand how deepfakes are made, how to check authenticity signals, and how to respond if a peer is targeted. Systematic reviews of deepfake pornography indicate that women and girls are disproportionately affected, with cases involving minors rising rapidly, including in school environments. Surveys show that many victims do not report incidents due to fear of disbelief, ridicule, or retaliation. Training for teachers, counselors, and university staff can help them respond quickly and compassionately, collect evidence, and utilize swift escalation channels with platforms and law enforcement. Institutions can establish agreements with major platforms to prioritize the review of deepfake abuse affecting their students and staff, including cases that cross borders.

Policymakers also need to revise procedures so that victims do not bear the full burden of enforcing their rights against deepfakes. Standardized takedown forms, centralized reporting portals, and legally mandated support services can lighten the load during a crisis. Rules requiring platforms to find and remove exact copies and easy variations of a reported deepfake, rather than putting the burden on the victim to track each upload, are crucial. The Take It Down Act's requirement that platforms remove flagged content within 48 hours and prevent its reappearance reflects this need, even while civil liberties groups express concerns about overzealous filtering. Substantial penalties for platforms that ignore credible complaints, along with independent audits of their response times, can enhance compliance beyond mere box-ticking. Internationally, regional human rights organizations and development agencies can fund specialized digital rights groups in the global South to help victims navigate foreign platforms and legal systems.

For educators, administrators, and policymakers, the goal is to connect these layers. Rights over one’s image should be seen as a minimum standard, not a maximum limit. Schools and universities should adopt clear codes of conduct that treat non-consensual synthetic imagery as a serious disciplinary offense, independent of any criminal proceedings. Professional training programs for teachers and social workers can cover both the technical basics of generative AI and the psychological aspects of shame, coercion, and harassment. Public awareness campaigns should focus less on miraculous detection tools and more on simple norms: do not share, do not joke, report, and support. Educational institutions should not passively accept regulations; they are vital environments where the social significance of deepfake abuse is shaped and where deepfake image rights can take on real meaning or remain empty promises.

Deepfake image rights are still necessary. They signal that a person’s face, voice, and body should not be raw material for anyone’s experiments or fantasies. However, rights that exist mainly on paper cannot keep pace with systems that replicate abuse at nearly no cost. The statistics on non-consensual deepfakes, on children's exposure, and on victimization highlight that the problem is real and not limited to celebrities or election campaigns. It is part of daily digital life. Protecting students and educators requires a shift from individual lawsuits to shared infrastructure: technical verification, strong platform responsibilities, fast takedown pathways, and campus cultures that treat synthetic sexual abuse as a joint concern. Suppose we do not build that layered protection now. In that case, the next generation will inherit a world where their deepfake image rights appear strong on paper but are essentially meaningless in practice.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Crest Advisory. (2025). Police-commissioned survey on public attitudes to sexual deepfakes. The Guardian coverage, 24 November 2025.

European Parliament. (2025). Children and deepfakes. European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing.

Japan News Outlets. (2025). Japan grapples with deepfake pornography as laws struggle to keep up. AsiaNews Network and The Straits Times reports, October 2025.

Kira, B. (2024). When non-consensual intimate deepfakes go viral. Computer Law & Security Review.

National Association of Attorneys General. (2025). Congress’s attempt to criminalize non-consensual intimate imagery: The benefits and potential shortcomings of the Take It Down Act.

New South Wales Parliamentary Research Service. (2025). Sexually explicit deepfakes and the criminal law in NSW.

Romero Moreno, F. (2024). Generative AI and deepfakes: A human rights approach to regulation. International Journal of Law and Information Technology.

Sippya, T., et al. (2024). Behind the deepfake: Public exposure, creation, and concern. The Alan Turing Institute.

Umbach, R., et al. (2024). Non-consensual synthetic intimate imagery: Prevalence, victimization, and perpetration. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

World Economic Forum. (2025). Deepfake legislation: Denmark moves to protect digital identity.

Comment