How China Rare Earth Export Controls Became the New Tariffs

Input

Modified

China quietly rations rare earths through strict export paperwork, not formal bans Its dominance in mining and magnet production turns bureaucracy into global leverage Schools and policymakers must plan for lasting supply risk and build alternative sources

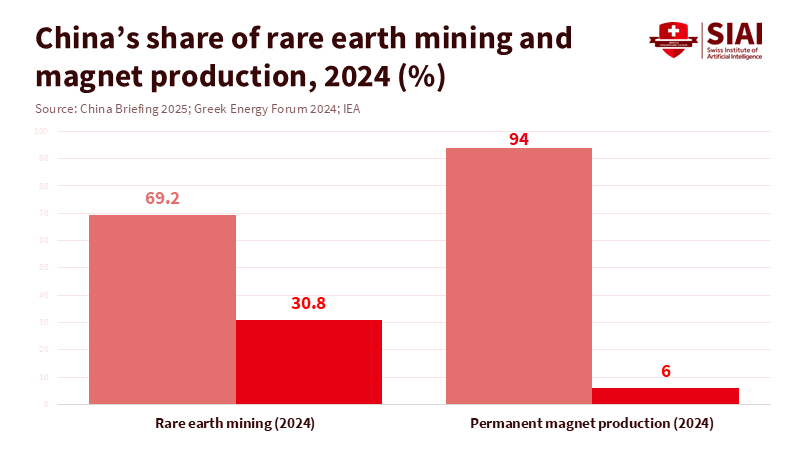

In 2024, China accounted for about 94 percent of the world's high-performance rare-earth permanent magnets, highlighting its dominant role and the associated supply chain risks. It also accounted for roughly 60 percent of rare-earth mining and 91 percent of refining. This concentration gives one organization significant power over the motors in electric cars, the drives in drones, and the magnets in medical scanners and factory robots. In early 2025, China did not announce an embargo on rare earths. Instead, it implemented a complex licensing system that considerably slowed exports. Shipments of magnets to South Korea and Japan dropped by more than 90 percent from March to May 2025. Monthly magnet exports fell to about US$60 million, the lowest level in a decade outside pandemic months, despite no formal export ban. This is the new approach to China’s rare-earth export controls: not three-digit tariffs, but layers of paperwork that act as invisible customs barriers. The challenge for policy and education is how to teach and govern in a world where forms and license codes hold as much weight as prices.

China's rare earth export controls as invisible tariffs

The main feature of the 2025 system is that it restricts access rather than raising headline prices. On April 4, 2025, Beijing imposed export controls on seven heavy rare-earth elements, along with the magnets and compounds that use them. This includes dysprosium and terbium, which are essential for high-temperature motors in electric vehicles, wind turbines, and defense systems. Companies trying to ship these items must now apply for a license for each shipment. Officials can take up to 45 working days to process an application under China's dual-use export rules. Traders report that some cases have taken months as ministries and customs request more documents and tests. Throughout this time, goods remain in warehouses or ports, production schedules are disrupted, and buyers scramble for alternatives. On the surface, China’s rare earth export controls seem like neutral regulation. However, they operate like a queue in which Beijing decides who goes first.

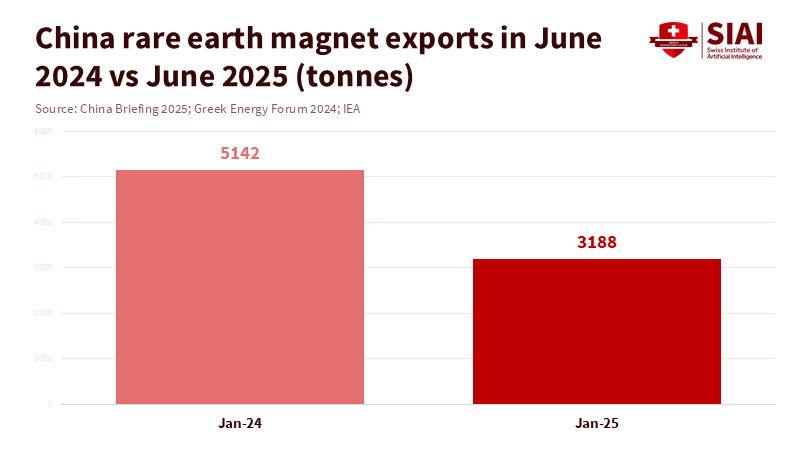

Customs data highlight how administrative obstacles, rather than a legal ban, disrupted supply. In the months following the April rules, China's rare earth exports grew only 4.8 percent year-on-year in April, then fell 5.7 percent in May, before rebounding by 60.3 percent in June as delayed licenses were processed. For magnets, the decline was sharper, with exports to South Korea and Japan plummeting by 93 percent and 91 percent, respectively, from March to May. Some carmakers in India and Japan temporarily reduced production of new electric models because motors could not be finished on time. Other manufacturers turned to short-term stockpiling when licenses became more readily available. Meanwhile, prices did not move uniformly. The International Energy Agency notes that, following these measures, some rare earth prices in Europe surged to as much as six times the Chinese domestic level, as overseas buyers paid higher prices for materials they could trust would arrive. This is what invisible tariffs look like: no public increase in the official tax rate, but higher costs and increased uncertainty for everyone outside the dominant jurisdiction.

How paperwork rationing works in practice

The specifics of China’s rare-earth export controls reveal why the regime operates more as a bureaucratic bottleneck than a straightforward quota system. Exporters face a “one batch, one license” policy. Each shipment requires its own approval, with detailed documentation of product composition, intended use, end-user identification, and even photos or videos of the destination facilities. A single error—such as a missing stamp, a vague end-use description, or an inconsistent HS code—can lead to the file being returned for clarification, pushing a shipment into the next month's queue. Customs officers can require chemical testing or product-code checks even for borderline items that are close to, but not on, the control lists, further delaying shipments. Legal documents call this due diligence; buyers view it as a series of mini-embargoes.

Advice from magnet producers in China makes this even clearer. One manufacturer notes that shipping sintered NdFeB magnets containing dysprosium or terbium now requires a signed end-use certificate, detailed technical reports, test results from a recognized lab, and proof that the magnets will not be used for sensitive military or nuclear purposes. License reviews commonly take 20 to 30 working days, and exporters are advised to allow a 45-day buffer. The company emphasizes that there is no complete export ban: compliant applications are approved. But “compliant” now means navigating a complicated maze of forms that many small buyers find challenging to understand. In any unclear system like this, firms worry that personal connections and local knowledge can influence how rules are interpreted. Even the perception that relationships matter, whether accurate or not, shifts bargaining power toward those who are closest to the licensing desks. This is a key reason why many downstream users feel that China’s rare earth export controls function more like a discretionary tax on time than neutral regulation.

The outcome is a structural advantage for large, established customers and politically less sensitive sectors. Major automakers and industrial groups can employ compliance teams, create standard document packages, and maintain regular contact with exporters and customs officials. Meanwhile, smaller businesses, universities, start-ups, and suppliers in emerging economies often cannot. When license approvals slow or criteria tighten, it is easier for authorities to delay shipments to new or less significant buyers than to cut off a flagship customer who could prompt diplomatic complaints. Over time, this encourages consolidation of demand among firms best equipped to handle the administrative burden. It also increases reliance: once a company has invested in the personnel and systems needed to navigate China’s rare-earth export controls, the cost of switching to suppliers not linked to China rises sharply.

The global influence of China’s rare earth export controls

The measures introduced in October 2025 extend the system beyond border management and into extraterritorial control. New rules require licenses not only for exports from China but also for re-exports between third countries of magnets and materials that include specified Chinese rare earth components or are produced with Chinese-origin technology. Suppose a magnet made in Europe contains even 0.1 percent of the selected Chinese rare earth materials by value. In that case, exporting that magnet to a third country may fall under Chinese jurisdiction. The list of controlled items now includes 12 of the 17 rare earth elements, as well as various alloys, oxides, permanent magnets, sputtering targets, and processing and recycling equipment. Additionally, a “50 percent rule” means that if a company is on China’s export control list or watch list, its majority-owned subsidiaries abroad could also face presumptive license denials.

For companies around the world, this transforms China’s rare earth export controls into a web that envelops entire supply chains, not just the moment when ore leaves a Chinese port. To comply, businesses must trace the origin of rare earth content through their suppliers, monitor the value of Chinese content, and determine whether any of their customers fall into military or restricted-end-user categories. Exporters are also required to send compliance notices down the chain, informing downstream buyers of their own responsibilities. The administrative load is heavy, but it also produces a steady stream of detailed information about who uses which rare earths. In these products, for what purposes, and in which locations? Given China’s dominance in refining and magnet manufacturing—exporting around 58,000 tonnes of rare earth magnets in 2024 alone—this gives Beijing a uniquely clear, almost real-time view of the global industrial network built on its materials.

Critics argue that China is simply adopting tactics long used by the United States and its allies and that these export controls are a defensive response to chip bans, sanctions, and additional tariffs. There is some validity to this: the 0.1 percent de minimis threshold and the foreign-direct-product-style language reflect US regulations on advanced semiconductors, and the 50 percent rule resembles a recent US update to its Entity List framework. Chinese officials also emphasize national security and the risk that rare earth technologies could support foreign weapon systems. However, what distinguishes the current situation is the combination of these legal tools with near-monopoly power. When one country processes over 90 percent of the world’s rare-earth magnets and produces 94 percent of key permanent magnets, its paperwork does not merely influence its own exports. It determines whether factories, research labs, and even universities on other continents can operate their equipment at all. This combination of legal reach and structural control is why educators and policymakers cannot regard this as just a niche trade law issue.

What educators and policymakers should do now

For the education sector, China’s rare-earth export controls pose both operational threats and a significant teaching opportunity. Technical universities, engineering schools, and vocational institutes depend on equipment that uses rare-earth magnets, including robotics arms, precision motors, MRI scanners, drone kits, and advanced machine tools. Many of these systems use magnets manufactured in China. Administrators who overlook licensing risks might eventually find that new machines cannot be delivered on time, spare parts are delayed, or warranty replacements get stuck in export paperwork. An immediate step is to ask fundamental questions: which critical devices on campus rely on rare earths, where their magnets originate, and whether alternative suppliers in countries like Japan, the United States, Australia, or the EU could be included over the next five years? Even partial diversification can lessen exposure to sudden paperwork shocks.

Educators must also view China’s rare-earth export controls as a current case study of how economic statecraft operates in the 2020s. Economics and international relations courses often focus on tariffs, quotas, and currency manipulation. Students now need to grasp licensing queues, end-use control, extraterritorial rules, and how compliance data becomes a strategic resource. Law programs can compare recent Chinese regulations with the US and EU export control frameworks to teach different approaches to dual-use technologies. Engineering curricula can include modules on materials security, asking students to redesign motors or devices to use fewer controlled elements or to prepare for sudden supply disruptions. Business schools can simulate how cash flow and delivery schedules respond when license approvals are extended from 20 to 60 days.

Policy makers, on the other hand, must move beyond the expectation that diplomatic agreements alone will “fix” the issue. China has already demonstrated its ability to pause parts of its October regime while keeping April controls in place, allowing for a later tightening. This suggests a future of fluctuating tensions timed to negotiations and summits. Governments in importing countries should view China’s rare earth export controls as ongoing and administrative. This means supporting alternative mining, refining, and magnet projects, even if they seem costly in the short term. It involves funding research into material substitutes and creating shared stockpiles of critical components, similar to what oil-importing countries did after the 1970s shocks. It also means investing in compliance capabilities, especially for smaller firms and public institutions that lack in-house legal teams but remain exposed.

A realistic policy agenda should also brace for criticism. Some observers caution that establishing parallel supply chains outside China could result in wasteful duplication and higher costs for green technologies. However, evidence from 2025 suggests that reliance carries its own costs. When Europe faces rare-earth prices several times higher than those in China and when an administrative hold can delay tens of thousands of tonnes of magnet exports, the hidden costs of concentration become apparent. The goal is not to completely exclude China but to ensure that no single set of forms in a single ministry can determine whether the world’s EV factories, data centers, or research labs can continue operating.

A world where one country produces 94 percent of critical permanent magnets and refines over 90 percent of key inputs has effectively given part of its industrial future to that country's administrators. China's rare earth export controls illustrate how that power can be wielded quietly, through queues and inquiries rather than dramatic embargoes. Educators can respond by teaching a new understanding of paperwork and power. Administrators can respond by identifying and reducing reliance on single points of failure. Policymakers can support slow, sometimes costly diversification and help smaller players navigate complex rules. If we do not act, the next time a form sits unanswered in a Beijing office, the cost will show not only in delayed shipments but also in canceled classes, stalled research, missed climate targets, and weakened security. If we act now, we can treat bureaucracy not as an unpredictable weapon but as one risk among many that our institutions are trained to handle.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

China Briefing (2025). China’s rare earth export controls – impacts on businesses and industries.

Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer (Liu, X., Yousef, N., Brown Cripps, S., & Peng, P.) (2025). China intensifies export controls over rare earths and related technologies.

International Energy Agency (2025). With new export controls on critical minerals, supply concentration risks become reality.

Mainrich Magnets (2025). China’s 2025 rare earth export controls: A comprehensive guide for importing sintered NdFeB magnets.

Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (2025). Regulations and announcements on export control of dual-use items and rare earth products (including Announcement No. 18/2025 and Notifications Nos. 55–62/2025).

Thow, K. (2025). China leverages paperwork to ration rare earths.

White & Case LLP (Hsiao, J., Li, L., Li, B., & Scoles, S.) (2025). China imposes extraterritorial jurisdiction and a 50% Rule for export controls on rare earth elements and other items.

Comment