China Tariff Transshipment and the Illusion of Decoupling

Input

Modified

US tariffs pushed Chinese exports through Southeast Asia instead of stopping them Factories and supply chains there still rely heavily on China Trade policy must target real value chains, not just flags on shipping labels

Vietnam's exports to the United States grew from about 46 billion dollars in 2017 to around 127 billion dollars in 2022. This represents a nearly threefold increase over five years. Detailed shipment data reveals the reasons behind this rise. About 8.8% of the increase came from Chinese goods now shipped to the U.S. via Vietnam rather than directly from China. Approximately 39.8% resulted from new Vietnamese value added. In comparison, another 20.4% came from additional Chinese inputs included in those "Vietnamese" exports. In short, China's tariff transshipment has turned a two-country tariff struggle into a three-region scenario. It has also obscured what trade statistics actually tell us about who produces what and where. If trade policy continues to treat these numbers as straightforward facts, tariffs will not hit their targets. Jobs will shift on paper rather than in reality, and the firms most skilled at changing labels will benefit the most.

Rethinking China Tariff Transshipment as a Deliberate Strategy

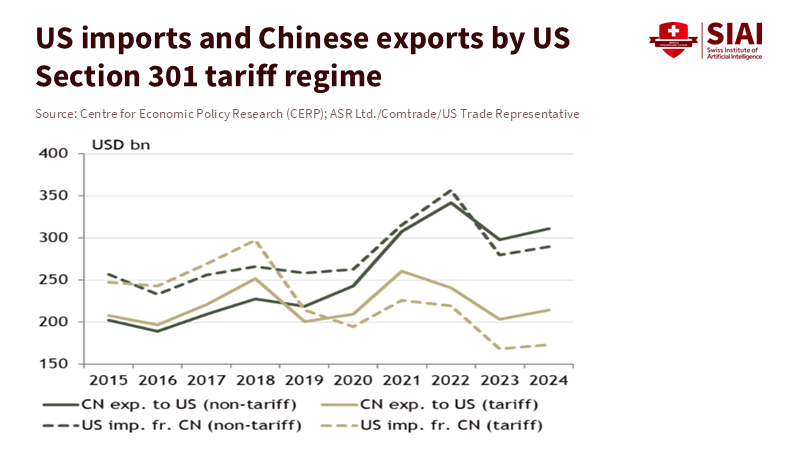

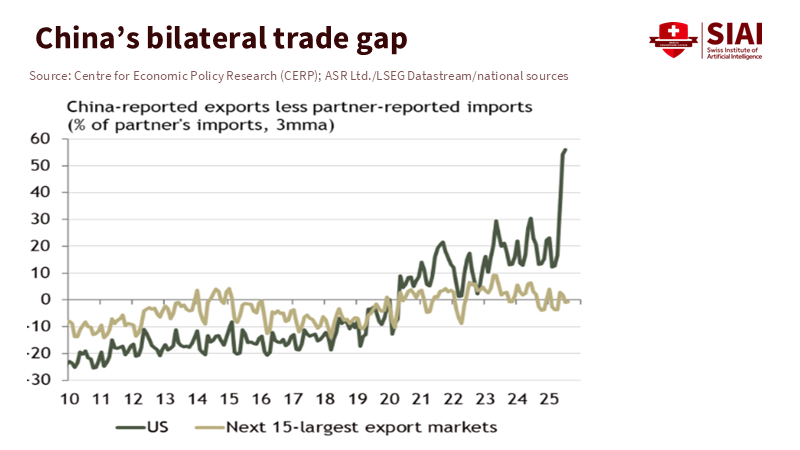

The standard narrative about recent U.S. tariffs is straightforward. Higher duties pushed American buyers away from China, forcing Chinese exporters to absorb the costs. There is some truth to this. The share of U.S. goods imports from China dropped from about 21% in 2018 to around 14% in 2023. During the same period, China's exports to the U.S. fell from roughly 19% of its total exports to 14%, and from 3.5% of its GDP to 2.9%. However, this is not a clean break. For products affected by U.S. tariffs, the share of Chinese exports taken in by the rest of the G20 rose from about 43% in 2017 to more than 52% in 2023. Much of this change is due to China's tariff transshipment and redirection rather than proper decoupling.

New microdata clarify the trend. An analysis of transactions in Vietnam indicates that an average tariff hike of 12.5 percentage points on Chinese goods led to a 1.74 percentage point increase in rerouting through Vietnam, resulting in a rise of over 14% compared to pre-war levels. Firms owned by Chinese and Hong Kong interests account for over half of this trade-war-induced rerouting. Almost all of the increase stems from new firms that established themselves in Vietnam after the tariffs were announced. In summary, China's tariff transshipment is not a side effect; it is a planned approach, supported by new capital and legal entities based in Southeast Asia while remaining closely connected to Chinese supply chains and finances.

This strategic shift was possible because companies had prepared in advance. Long before the first tariffs in 2018, multinational firms with strong ties to China began creating “China plus one” networks in Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and other neighboring countries, often for final assembly and labor-intensive stages. When tariffs took effect, these positions enabled firms linked to China to redirect orders, modify paperwork, and expand new plants, whose legal identities changed but whose core suppliers and technology did not. The error lay not only in the magnitude of the tariffs but in assuming that origin-based duties could follow a supply chain that now treats borders as mere administrative details. For educators and policymakers, the takeaway is that trade rules designed for a straightforward world of bilateral flows will consistently underestimate how quickly firms adjust.

How China Tariff Transshipment Reshaped Southeast Asia’s Gains

For Southeast Asian economies, China's tariff transshipment has brought both opportunities and challenges. Vietnam serves as a clear example. Between 2018 and 2024, China’s exports to Vietnam increased at a compound annual rate of around 18.7%. During the same period, U.S. imports from Vietnam rose by roughly 15.7% annually. Thailand shows a similar trend, with Chinese exports to Thailand growing at about 10.5% per year and Thai exports to the U.S. increasing by around 10.4%. These paired surges are difficult to explain without considering both transshipment and real relocation. New factories, many owned or supplied by Chinese companies, have created jobs and tax revenue. Export figures appear impressive, allowing governments to highlight double-digit growth as proof that they turned the U.S.–China tariff conflict into an opportunity.

The broader regional context supports this view. ASEAN has surpassed the U.S. and the EU as China’s largest export market. By 2024, approximately one-sixth of all Chinese exports went to Southeast Asia. Much of this trade involves intermediate goods, such as electronic components, steel, and plastics, which feed factories that then ship final products to Western markets. A striking example is solar energy. In 2023, the U.S. imported about 11.9 billion dollars in solar cells from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Many of these exports originated from factories linked to Chinese manufacturers that shifted parts of their production chains into the region. Here, China tariff transshipment fits into a larger pattern: China provides the key inputs, Southeast Asia assembles the final products, and the goods enter the U.S. market under a different label.

At the same time, the benefits are more complex than a straightforward “China loses, ASEAN wins” narrative. The evidence from Vietnam shows that only 8.8% of the export growth to the U.S. between 2018 and 2021 is due to rerouting Chinese goods. Nearly 40% reflects increased domestic value added, with the rest coming from imported inputs, including a 20.4% contribution from non-rerouted Chinese content. Tariffs have, therefore, accelerated two interconnected processes. They have enabled Southeast Asian economies to move up the value chain. Still, they have also increased their reliance on Chinese intermediate goods and capital. Local workers enjoy factory jobs, but many higher-margin areas—like design, core components, and sometimes branding—remain under Chinese or other foreign control.

These shifts are now facing a second “China shock” in the region. Chinese exports to ASEAN have reached all-time highs, and domestic producers in sectors like steel and consumer appliances report intense competition from cheaper imports. Governments that once welcomed every new Chinese factory are now concerned about the impact on local firms. They also encounter new diplomatic pressures as Washington advocates for stricter rules on China tariff transshipment, including punitive tariffs on goods it views as disguised Chinese exports and bilateral agreements that impose extra duties on transshipped products. Southeast Asia finds itself in a tight spot: eager to attract investment and jobs but cautious about becoming a permanent buffer zone in someone else’s tariff conflict.

Measurement, Misinformation, and Policy Errors in China Tariff Transshipment

One key lesson for educators and officials on China tariff transshipment is the importance of accurate measurement. Trade statistics still depend on customs declarations that assign each shipment to a single country of origin. Tariffs aimed at specific origins give firms a strong incentive to change that label. They can route goods through a third country, perform minor processing, or structure ownership so that a Chinese-controlled factory in Vietnam counts as Vietnamese for customs purposes. When resulting shipments are recorded under new flags, import data starts to present a misleading picture of substitution. It seems buyers have moved away from China, even as Chinese inputs, machinery, and management remain central.

The Vietnam study highlights the significance of this misunderstanding. Suppose we rely solely on country-level trade totals. In that case, it appears that over one-fifth of Vietnam’s export growth to the U.S. after 2018 is attributed to rerouting from China. However, once researchers trace shipments at the individual-product, province, and firm levels, the share drops to 8.8%. The rest of the growth stems from genuine new production and an increased share of imported inputs, particularly from China. Firms owned by Chinese and Hong Kong interests dominate the response to rerouting. New establishments are particularly influential, showing that many of the entities formed during the trade war were created with evasion in mind. Simultaneously, journalists and analysts report a rise in “origin washing,” in which Chinese exporters offer services to relabel goods in countries like Malaysia and Vietnam so they can enter the U.S. without the same tariffs as those on goods from China.

These details matter for policy and how we teach economic models. Suppose students and analysts take trade data at face value. In that case, they may input it into models that view Vietnam or Thailand as simple substitutes for China. Those models will suggest that origin-based tariffs can lead to significant sourcing shifts at low cost. In reality, much of the supposed “diversification” is superficial. Final assembly moves, but core suppliers do not. Global organizations also indicate that the wave of trade barriers is growing quickly. The IMF counts around 3,000 trade restrictions worldwide in 2023, up from about 1,000 in 2019. They warn that severe fragmentation of trade into opposing blocs could reduce global output by as much as 7%. When China's tariff transshipment obscures the trustworthy source of goods, new tariffs aimed at third countries risk creating more distortions. The result is layered protection and confusing data, along with only slight changes in where value is truly made.

Teaching the Next Generation to See Through China Tariff Transshipment

All of this should change how trade and industrial policy are taught in schools, universities, and executive programs. Many students still learn from neat diagrams where tariffs clearly shift imports from one country to another. The story of China tariff transshipment shows that this model no longer applies. Economics, business, and public policy courses should place greater emphasis on supply chain mapping, ownership structures, and rules of origin. Case studies from Vietnam, Thailand, and the solar industry can help students understand how a single product can cross multiple borders, change legal nationality numerous times, and still depend on the same set of Chinese components and designs at its core.

Educators also need to re-emphasize distributional effects in their discussions. U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods did not trigger a widespread manufacturing resurgence at home. Research shows that the costs largely fell on U.S. firms and consumers. At the same time, production shifted to third countries, and exports from China were redirected rather than collapsing. In Southeast Asia, the benefits from China tariff transshipment have been real but uneven. Regions focused on exports, large companies, and workers with the necessary skills have prospered. Smaller local producers often face tougher competition from both Chinese inputs and Chinese-linked final goods. IMF research on ASEAN highlights that positive spillovers from the trade war have increased value added, but also warns that future growth depends on maintaining open markets and building domestic capabilities rather than acting solely as low-margin assembly bases for foreign supply chains.

For policymakers, the message is clear. If the ultimate goal is to reduce reliance on Chinese supply chains, tariffs tied to origin labels are not an effective tool. They lead to tariff transshipment through China, reward quick but superficial plant relocations, and push trade flows into statistical blind spots. More targeted approaches should focus on the specific technologies and products that are security-sensitive, regardless of where the final assembly occurs. These strategies would invest in domestic skills, infrastructure, and innovation, while supporting partners in Southeast Asia who want to advance up the value chain rather than remain low-margin assembly centers.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

The final question for an education journal is straightforward. What will tomorrow's trade lawyers, economists, and business leaders see when they examine the post-2018 trade landscape? If they notice only a sharp decline in the U.S. share of imports from China, they might conclude that tariffs “worked” and advocate for more of the same. Suppose they recognize the whole reality of China's tariff transshipment, the surge in Chinese exports to ASEAN, and the modest decrease in China's overall export income to the United States. In that case, they will understand that the situation is more complicated. Tariffs have changed where boxes are stamped, not where value and control actually lie. Reflecting on Vietnam's dramatic export growth reveals both real local development and a subtle Chinese influence in the background. Teaching this distinction clearly is not just an academic responsibility; it is a practical safeguard against repeating a costly policy experiment that altered trade statistics more than it transformed the structure of global production.

Brooks, R. (2025, June 20). China’s transshipment of goods to the U.S. Brookings Institution.

CaixaBank Research. (2024). Exposure of the Chinese economy to a U.S. tariff hike. CaixaBank Research.

China Briefing. (2025). China’s transshipments through Southeast Asia – impact of U.S. tariffs. Dezan Shira & Associates.

Financial Times. (2025, May 4). Chinese exporters “wash” products in third countries to avoid Donald Trump’s tariffs.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Analytical Corner: Global trade policy spillovers to ASEAN. IMF Annual Meetings.

Lawder, D. (2024, May 16). IMF: U.S. should keep open trade, work with China to resolve disputes. Reuters.

Iyoha, E., Malesky, E., Wen, J., & Wu, S.-J. (2025). Exports in disguise? Trade rerouting during the U.S.–China trade war (HBS Working Paper 24-072). Harvard Business School.

Comment