Actuarial Neutrality and Early Retirement: Why Public Finance Cannot Ignore the Capital Base

Input

Modified

The article expands actuarial neutrality from pensions to the whole public budget It shows how early retirement weakens tax revenues, pension capital, and debt sustainability It urges linking retirement-age rules to public-finance neutrality while protecting vulnerable workers

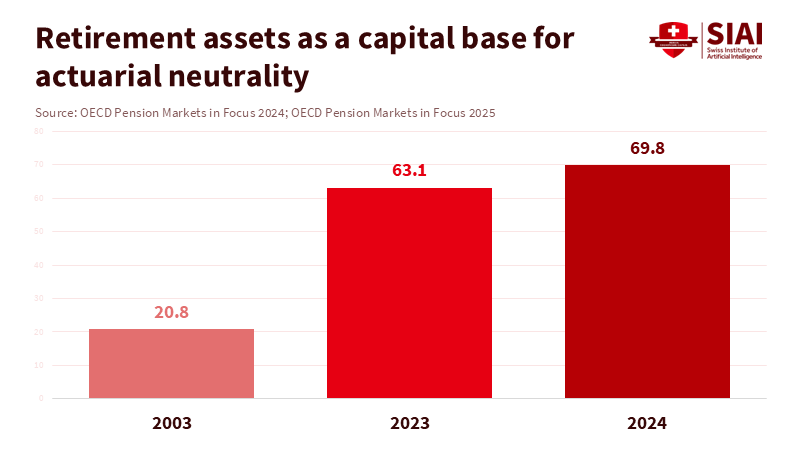

In new modeling for France, the "true" cost of early retirement nearly doubles when we consider the entire public budget. Retiring one year earlier, without changing other taxes or spending, would lead to an 11% cut in the annual pension to balance public finances. This compares to about a 6.7% cut when focusing solely on pensions. That difference isn’t just a technical detail. It shows that we undervalue early retirement by overlooking its effects outside the pension system, such as lower tax revenues, reduced ability to manage public debt, and a smaller long-term capital base for education, healthcare, and infrastructure. At the same time, retirement assets in OECD countries have tripled over two decades, reaching around USD 63.1 trillion. This amount is about 10% higher than in 2022 but still below the 2021 peak. These pension and reserve funds are crucial in global capital markets and public finance. Therefore, any serious discussion about retirement ages must start with actuarial neutrality in public finance, not just pensions.

Actuarial neutrality in public finance is about more than pensions

Actuarial neutrality in public finance goes beyond pensions. The basic idea of actuarial neutrality is straightforward. A pension system is neutral if, for someone with an average life expectancy, the present value of contributions matches the present value of benefits, regardless of retirement age. In simpler terms, retiring earlier means receiving benefits for more years but getting lower monthly payments. Conversely, working longer gives fewer years of benefits but higher monthly payments. For example, in the United States, Social Security cuts benefits by about 5–6% for each year of early claiming compared to the full retirement age, applying a reduction of 5/9 of 1% per month for the first three years and 5/12 of 1% per month thereafter. This structure aims to be roughly actuarially neutral within the pension system. However, it doesn’t address the entire state budget.

Recent research reframes the idea of actuarial neutrality and extends it to all public finances. When we consider how retirement choices impact general tax revenues and non-pension spending, the "neutral" schedule becomes much steeper. A study using realistic French numbers in a pay-as-you-go system finds that retiring one year early incurs a penalty of about 6.66% when we focus only on pension balances, but this jumps to 11.1% when we account for keeping the entire public budget stable at a specific tax rate and spending level. In this broader context, actuarial neutrality is not just a fair exchange between working longer and enjoying more leisure. It also includes recognizing the external costs of early exit on healthcare, education budgets, and debt sustainability. Given that public pensions already account for about 7.7% of GDP on average in OECD countries, with Greece and Italy exceeding 15%, neglecting this broader fiscal connection is no longer justifiable.

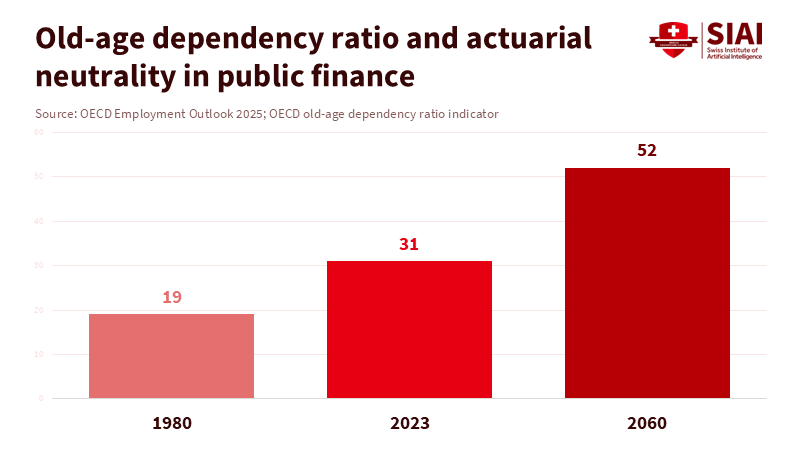

Demographic pressure is pushing the system in the opposite direction. The percentage of individuals aged 65 and over in OECD countries has more than doubled since 1960 and is expected to reach about 30% of the population by 2060. The old-age dependency ratio, which refers to the number of individuals aged 65 and older for every 100 people of working age, has also more than doubled since 1960. Without policy changes, OECD estimates suggest that population aging alone could increase fiscal pressure by around 6¼ percentage points of GDP from 2024 to 2060, with pensions, healthcare, and long-term care accounting for most of the strain. Extended actuarial neutrality is a way to align retirement incentives with this new reality. It recognizes that early retirement is not just a personal choice with personal costs but also a demand on limited fiscal and capital resources.

How early retirement erodes the capital base of public finance

The capital-market aspect of actuarial neutrality in public finance often gets overlooked. Yet, this could be where the long-term damage is most significant. Pension providers and public pension reserve funds in the OECD manage about USD 63.1 trillion in assets, three times their level in 2003. However, at the end of 2023, those assets were still about 5% below their 2021 peak following the 2022 rate shock. A separate global study of 22 major markets finds pension assets totaling USD 47.9 trillion, roughly 62% of GDP, with the United States, Japan, and Canada accounting for more than three-quarters of this amount. These capital pools are not just idle savings. They are key buyers of government bonds, significant investors in infrastructure and real estate, and critical limited partners in private equity and private credit.

As interest rates remained low during the 2010s, pension funds and public plans invested heavily in alternative assets. In the US, nearly 88% of public pension funds now allocate capital to private equity, with a median of about 14% of total assets and ten-year annualized returns over 15%. Globally, pension funds represent about a fifth of all capital raised by European private equity and venture funds. From 2001 to 2023, US public pensions shifted around 20 percentage points of their portfolios away from traditional stocks and bonds toward alternatives such as private equity, infrastructure, and private debt. Life insurance companies have made similar adjustments. In Europe, insurers continue to invest significantly in government and corporate bonds, with around 87% of their sovereign bond holdings, 80% of their equities, and 75% of their corporate bonds being European assets, thus supporting local capital markets.

These institutional investors are central to non-bank finance. The Financial Stability Board estimates that non-bank financial intermediaries hold about 47% of global financial assets. At the same time, recent IMF findings indicate that insurers, pension funds, and investment funds together hold roughly two-thirds of those non-bank assets. According to the European Central Bank, the largest domestic holders of sovereign bonds in the euro area include banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and investment funds. When these investors change their strategies, bond markets respond. For instance, Dutch pension funds are expected to sell around €125 billion in long-dated government bonds from 2025 to 2028 as their system transitions from defined-benefit to defined-contribution plans, applying pressure to an already strained €10 trillion European government bond market.

Early retirement interacts with this capital structure in subtle yet impactful ways. When many workers exit the labor force before the statutory age, contributions stop, benefits commence, and the net cash flow of pension systems declines. The latest OECD data show that, despite years of reform, only about 55.9% of individuals aged 60–64 were employed in OECD countries in 2024, with significant variation across countries. This means nearly half of this age group is already out of work. Every additional year a large group remains in employment, especially at high wages, contributes to the budget and to funding for pension and insurance funds. Conversely, every extra year of early retirement has the opposite effect. Over time, this alters the growth path of retirement-linked assets, affecting the supply of long-term capital available for both public and private investments.

Actuarial neutrality in public finance should guide retirement-age policy

Actuarial neutrality in public finance should inform retirement-age policy. Let's take actuarial neutrality in public finance seriously. Retirement-age policy becomes a fundamental macro-financial factor rather than a mere social choice. The earlier French example illustrates this starkly: a one-year change in retirement age requires an 11.1% adjustment in pension benefits to keep both pensions and other public budget elements balanced, compared to a 6.66% adjustment when considering pensions alone. The discrepancy occurs because working an additional year increases GDP, tax revenues, and contributions while deferring benefit payments. In an aging society where pension spending already accounts for 7.7% of GDP on average, gaining that extra fiscal space is crucial. It helps governments sustain education budgets, climate initiatives, and healthcare without pushing debt to risky levels.

Extended actuarial neutrality provides a straightforward way to incorporate this trade-off into policy rules. Instead of debating single increases in retirement age—like 62 to 64 in one country or 65 to 67 in another—governments can publish clear tables that connect retirement age, pension amounts, and the health of public finances. Here, the condition of actuarial neutrality covers the entire budget: contributions and general taxes must meet pension and other spending needs at a specific tax rate. Suppose people retire earlier than the reference age. In that case, their pensions adjust not only for the extra years of payments but also for the lost fiscal resources. If they retire later, they receive a larger bonus because they also help create surplus funds outside the pension system. This approach doesn’t eliminate politics, but it provides a foundation for discussion based on a shared understanding of budget constraints.

For policymakers, the message is clear. It’s not enough to evaluate whether a pension reform is “generous” or “harsh” within the pension system. The real test is whether the reform aligns with actuarial neutrality in public finance. Recent OECD long-term forecasts indicate that without reforms to extend working lives and enhance participation, aging could increase fiscal pressure by around 6¼ percentage points of GDP by 2060. A strategy that reduces pathways to early retirement and ties retirement ages to gains in life expectancy, along with labor market reforms, could reduce that pressure by about 4 points of GDP. This is the scale to consider when evaluating small changes in early retirement rules alongside the stability of education funding, research budgets, and the costs of public debt.

Making actuarial neutrality fair for shorter lives and more complex jobs

Making actuarial neutrality fair for shorter lives and more demanding jobs raises valid concerns. Workers with lower incomes, unstable careers, or physically demanding roles tend to retire earlier, often with shorter life expectancies. A steeper penalty for early retirement, intended to achieve actuarial neutrality in public finance, could disproportionately affect these groups. The literature highlights this issue, emphasizing the need for flatter schedules in some situations to protect against late-career unemployment and health challenges. Overlooking these equity concerns would be misguided. However, they are not grounds to discard the extended concept; instead, they prompt us to design it better.

The correct approach is to distinguish two intertwined questions. The first is how steep the actuarial-neutrality schedule should be at the macro level, given the need to safeguard public finance's capital base. The second is how to protect those who realistically cannot work longer without significant hardship. Policy can be more targeted here. Instead of flattening the entire schedule for everyone, governments can identify specific groups where early retirement is warranted—such as those with long careers starting young, high-risk jobs, or medically verified limitations—and provide targeted pathways with softer penalties. This could be funded through the broader system, including more progressive taxes on high earners over their lifetimes. This way, the macro signal of extended actuarial neutrality remains intact while addressing real concerns about fairness.

Education systems play a key role in this balancing act. Universities, vocational institutes, and online providers are essential to any plan that increases workforce participation among older adults. The OECD's work on aging highlights that policies supporting healthy aging, adult learning, and career transitions in later life can significantly lessen fiscal pressure by enabling more individuals to work into their 60s. This means the education sector is not just a passive victim of pension politics; it is part of the solution. Providers who create flexible, low-barrier training for workers in their 50s and 60s help make longer retirement ages practical, not just theoretical. A stronger capital base, which is supported by long-term fairness in public finance, helps stabilize the budgets that fund these programs.

Public discussions still frame retirement age as a narrow social compromise. In reality, it is a broader financial decision. The data is precise. Global pension assets are now in the tens of trillions of dollars, accounting for about 60% of GDP in key markets. These assets are significant buyers of government bonds and major suppliers of long-term capital to businesses, infrastructure, and housing. Additionally, careful modeling shows that when we consider the entire budget, the neutral adjustment for a one-year change in retirement age is closer to 11% than previously thought, rather than the previously estimated 6-7%. We have been undervaluing early retirement for years, and the consequences are now evident in increased debt, tighter education budgets, and weaker capital markets.

A new perspective is possible. We should view retirement-age policy as part of capital-market policy. Establish neutrality across the entire public budget, not just pensions. Create clear schedules that account for this broader constraint while protecting workers who cannot extend their working years. Then equip the education system and employers with the tools needed to make longer working lives feasible for most people. The choice isn't between dignity for older workers and fiscal responsibility. It is between a system that ignores the external costs of early retirement and one that recognizes that every additional year of work is also an investment in the capital base that sustains schools and staff hospitals and keeps national debt manageable.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

American Investment Council. (2024). 2024 Public Pension Study: Trends in private equity investing by US public pension funds.

Blanchet, D., & Cette, G. (2025). Pension design and general public finances: Beyond baseline actuarial neutrality. Economics Letters, 257, 112683.

EIOPA. (2024). Europe’s insurance and pension fund sectors stay resilient amid tense risk landscape. Financial Stability Report.

EQT. (2025). Pension funds and private equity – How they work together. ThinQ by EQT.

European Central Bank. (2025). The euro area bond market. Speech, 11 June 2025.

Financial Stability Board. (2023). Global monitoring report on non-bank financial intermediation 2023.

IMF. (2025). Agrawal, S. Pension funds and financial stability. IMF Note.

Invest Europe. (2024). Private equity activity 2023: Fundraising, investments & divestments in Europe.

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: OECD social indicators. Chapter 6: Social spending.

OECD. (2024). Morgavi, H. Is it worth raising the normal retirement age? A new model to estimate the employment effects. OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1823.

OECD. (2024). Pension Markets in Focus 2024. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2025). OECD Employment Outlook 2025: Navigating the golden years. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2025). Koutsogeorgopoulou, V., & Morgavi, H. The fiscal impact of population ageing: How can we afford getting older? ECOSCOPE blog, 7 November 2025.

Reuters. (2025). Europe’s bond market losing Dutch pension fund buyers as retirement payouts shift. Reuters Markets, 7 August 2025.

Social Security Administration. (2024). Retirement benefits: Early or late retirement. SSA.gov.

Comment