Rethinking the Green Bond Premium in Sovereign Debt

Input

Modified

The sovereign green bond premium is tiny and unstable Real value comes from standards, disclosure, and crowding-in private capital Treat the greenium as a signal; cut project risk with credible frameworks and predictable pipelines

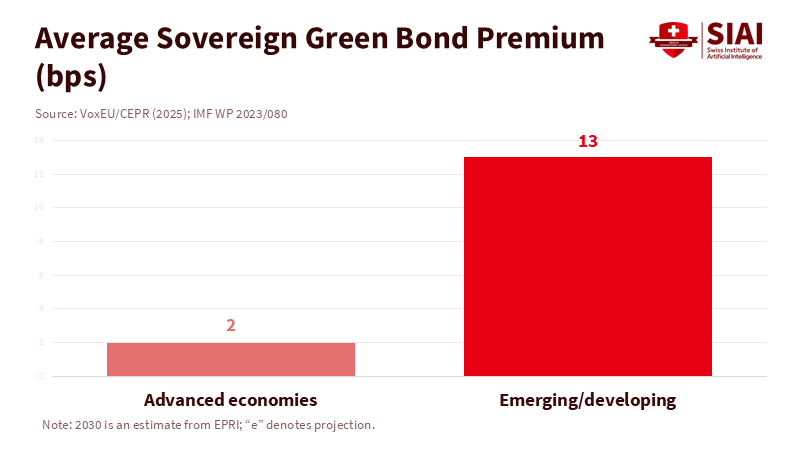

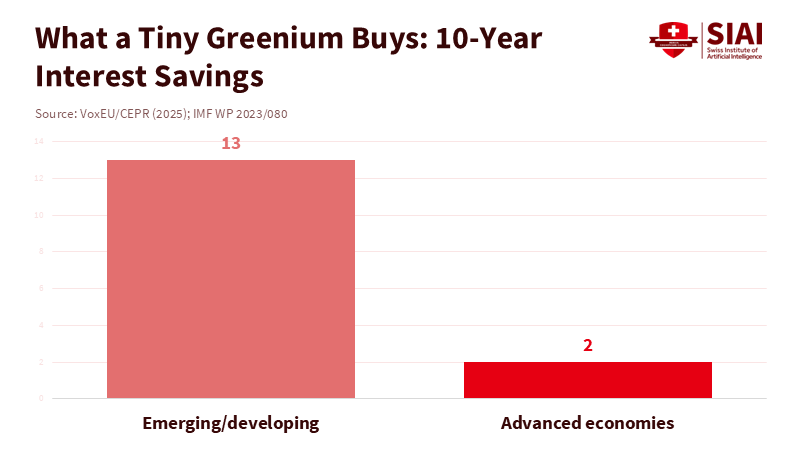

A striking number sits at the center of today’s debate: the green bond premium in sovereign markets appears to be only a few basis points, about two in advanced economies and a bit over ten in many emerging markets. That is often smaller than the bid-ask spread on the screen. If the green bond premium is that small, have markets really learned to price climate alignment, or are we chasing noise that fades with each auction cycle? The tension is real. Recent analyses confirm a discount exists, but it is surprisingly small and unstable over time, across different regimes, and among issuers. At the same time, the labeled market continues to grow in size and legal consistency, even as political challenges arise in the United States and elsewhere. The result is a paradox: the green bond premium may be too weak to affect fiscal calculations, yet the green label still influences market operations, disclosure, and investor outreach. The question is no longer “does a premium exist?” but “what is it excellent for?”

Defining the green bond premium in sovereign markets

At its core, the green bond premium, often called the “greenium,” is a yield discount that investors accept for a sovereign bond with designated green uses of funds compared to a similar conventional bond. When measured carefully—matching issuer, maturity, and other criteria—the discount is small. Recent cross-country studies estimate the average at around two basis points in advanced economies and roughly 13 basis points in emerging markets. This pattern aligns with earlier estimates of about four and 11 basis points, respectively. These are not game-changing numbers for a debt manager. They are real, but they fall within a range where liquidity and timing can obscure the signal.

Evidence from the euro area reinforces this point. Using spread measures that remove interest-rate risk, a targeted review of 21 sovereign green bonds issued since 2017 finds an average green bond premium of -2.8 basis points between 2021 and early 2024. The sign indicates a discount. The magnitude is fragile. It is smaller than many intraday changes and varies with supply, macro developments, and auction schedules. Even supportive observers now agree that the premium can disappear when issuance increases or when labels are less scarce. In short, the premium exists, but it is thin, volatile, and easy to misinterpret.

Evidence in 2023–2025: a small, unstable price effect

What has changed since the early days? The market has matured. Global issuance of labeled sustainable bonds surpassed $1.1 trillion in 2024, with green still the most common label; Europe accounted for most aligned green volumes and set the standard for practices. As the market grew and disclosure rules tightened, the scarcity that once bolstered the green bond premium decreased. A discount that was partly based on limited supply now competes with deeper order books and better benchmarks. The result is a more efficient market and a flatter premium, a sign of the market's evolution and increasing sophistication.

Policy also played a significant role in shaping the market. The EU Green Bond Standard became effective on December 21, 2024, introducing standardized disclosures, external review registration, and taxonomy alignment into a voluntary but thorough framework. That step improved integrity more than it improved price. The message is that “green” should signify something verifiable—even if the green bond premium does not consistently cover the issuer’s coupons. Standard-setting lessens greenwashing risks and enhances comparability, which investors appreciate. However, the main advantages show up in how the market functions, not in significant basis-point savings.

Then politics affected the situation. In 2025, U.S.-labeled issuances fell as firms “greenhushed,” funding clean projects without using the label. Global sustainable volumes also declined, with second-quarter activity being the weakest since 2019. These fluctuations do not indicate that climate investment is over. Instead, they show that labels fluctuate with policy risks. If the label’s usage declines amid political changes, the green bond premium linked to that label will decrease as well. Connecting fiscal expectations to a price gap that can disappear with an election is poor risk management.

If the green bond premium is tiny, where is the real value?

The most lasting public benefit from sovereign green issuance is not the green bond premium. It is the market infrastructure that green programs create. When governments issue bonds, they publish frameworks, allocation reports, and impact summaries. They make reference curves, build data sets, and ensure consistency in project tagging. Evidence suggests that sovereign programs act as catalysts; they help grow sustainable corporate markets by establishing templates and reducing search costs for investors. That effect—crowding in private issuance and enhancing information—can be larger than a two-basis-point discount on the sovereign curve.

Scale and integrity matter for another reason. Europe now holds the majority share of aligned green issuance, aided by taxonomy rules and the EU standard. This concentration creates liquid benchmarks in euros and supports index creation. It also enforces tracking of proceeds and post-issuance reporting. Even critics who doubt a lasting green bond premium acknowledge that the processes tied to the label have improved significantly since 2020, especially in China and Europe, where alignment shares and external reviews have increased. This is not a minor detail; it is a governance upgrade with tangible benefits for procurement, project selection, and auditing.

There is also a dynamic aspect to the green bond premium. When transition risk rises—after extreme weather, new regulations, or energy price spikes—the premium typically widens for vulnerable issuers. That is not a magic coupon; it is a measure. It indicates that investors are willing to pay a bit more for credible, taxonomically aligned assets when climate risk is prominent. However, the measure weakens when anxiety diminishes, issuance rises, or macro conditions shift. Policy should view the green bond premium as a signal to interpret, not a subsidy to rely on, highlighting the need for continuous market monitoring and adaptation.

Policy design when the green bond premium is not the point

Suppose the green bond premium is small and unpredictable. In that case, the best strategy is to optimize the program rather than chase small gains. That means issuing when the fiscal and duration windows are favorable, creating “twin” or benchmark lines that enhance liquidity, and prioritizing reporting that investors can trust. It also means resisting the urge to promise budget savings from labeling alone. Two or three basis points on one line can vanish with a week of macro data. What remains is credible governance of the use of proceeds under a common standard. The EU framework now provides that discipline; others can align substantively even without adopting the name.

There are more effective ways to lower capital costs for green infrastructure than waiting for a fluctuating green bond premium. Guarantee schemes for early-stage technologies, predictable auction schedules for clean energy, and stable carbon price floors all reduce risk premiums where it counts—the project level. Sovereign green programs can still help by building pipelines and publishing forward calendars that align with national transition plans. Yet, the price advantage from the label should be seen as a bonus, not the primary reason for action. Investors will continue to buy because projects address energy security needs and data center demand, regardless of the label’s popularity. The role of policy is to make the green helpful label even when it lacks profitability.

Skeptics raise valid points: if the green bond premium is only two basis points for wealthy-country treasuries and 12 for many others, it seems like a market flaw. That view misunderstands what the evidence currently shows. The premium exists but is thin; it widens when risk is present and shrinks when supply increases; it adjusts with politics; and it reveals more about market functions than about sovereign budgets. We should not base fiscal plans on it. We should develop credible green programs that improve disclosure, engage private capital, and maintain project pipelines in line with common standards. That is the work that will endure through cycles. The mandate for issuers is clear: continue issuing to establish benchmarks and data; align with rigorous standards; publish allocations and impacts on time; and consider any green bond premium as an extra, not the primary goal. If we do that, the market will still provide what matters—lower overall capital costs for the transition—even when the premium itself disappears.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AXA Investment Managers. (2025, January 22). The good, the bad, the opportunities: green bonds in 2025. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

Banque de France. (2024, December 13). Do green sovereign bonds benefit from a green premium? (Post 380, PDF). Retrieved November 20, 2025.

Cheng, G., Ehlers, T., Packer, F., & Xiao, Y. (2024). Sovereign green bonds: A catalyst for sustainable debt market development? IMF Working Paper 2024/120.

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2025, May 31). Global State of the Market 2024. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2025, June). Global State of the Market—Report (May 2025). Retrieved November 20, 2025.

European Commission. (2025, November 5). The European green bond standard – Supporting the transition (FAQ; applicable from December 21 2024). Retrieved November 20, 2025.

Financial Times. (2025, June). US borrowers opt for “greenhushing” of bond sales under Trump. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

IMF. (2023). Ando, S., et al. How large is the sovereign greenium? IMF Working Paper 2023/080. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

Nordic ESG Lab, Copenhagen Business School. (2025, July 18). No more greenium: What the vanishing green bond premium means for sustainable finance. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, July 23). Green bond issuance dives almost a third amid climate backtracking. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

VoxEU/CEPR. Panizza, U., Shi, S., Weder di Mauro, B., & Gulati, M. (2025, November 19). The unbearable lightness of the sovereign greenium. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

World Bank Treasury. (2025, February). Labeled Sustainable Bonds Market Update—Issue No. 10. Retrieved November 20, 2025.

Comment