Digital Mercantilism in Education Markets: What the U.S.-Korea Platform Clash Teaches Schools

Input

Modified

Digital mercantilism drives the U.S.–Korea platform fight in schools Make access reciprocal, data portable, and impact proven Treat ed-tech buying as trade policy to protect learning and competition

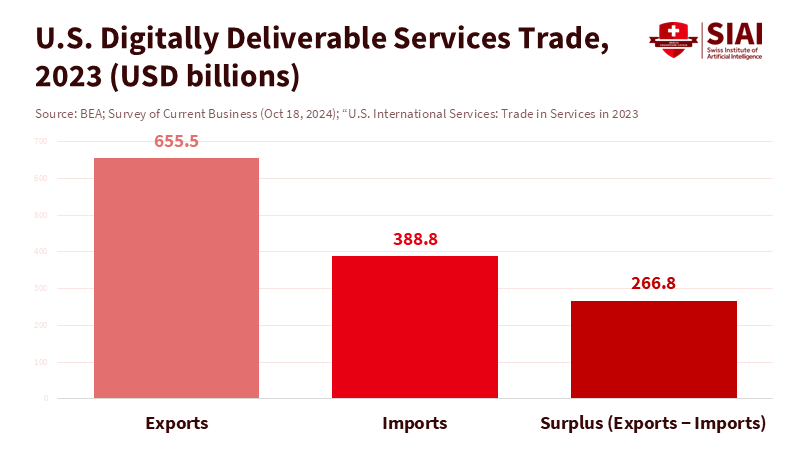

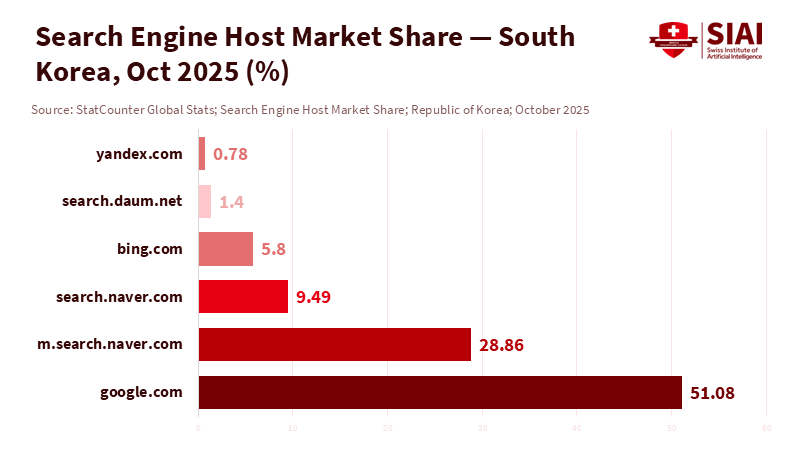

The most critical number in this debate is $266.8 billion. That was the U.S. trade surplus in "digitally deliverable services" in 2023. This isn’t just a number on a balance sheet; it represents the profit source behind app stores, cloud services, advertising technology, and the video and search platforms that influence what students see and how schools teach. When a country has a surplus this large in the digital space, rules affecting platforms start to resemble foreign policy. This is why presidents emphasize protecting “our incredible American tech companies.” Other countries react when those companies impact local services. South Korea illustrates this well. Google has a slight majority of search traffic in Korea, YouTube leads in social video, and YouTube Music has surpassed the long-standing local favorite, Melon. These conflicts are not cultural disputes; they are trade issues that have real effects in classrooms.

Digital mercantilism has entered the classroom

The policy struggle goes beyond tariffs or app store fees. It concerns which platforms become the standard for learning. YouTube is now the most frequently used platform among American teens, with seven in ten visiting daily. Teachers and students rely on it for lectures, labs, language lessons, and extra help. The same pattern is evident in Korea, where YouTube is the primary social media site. When one video platform captivates this much attention, choices in classrooms and national trade interests intersect. Arguments over “domestic regulation” turn into debates about the global market share of U.S. companies and the international spread of their data-driven business models. This is digital mercantilism in action: safeguarding surplus-generating platforms as essential assets while viewing other nations’ regulations as trade barriers.

Digital mercantilism also reshapes how we interpret presidential statements. When leaders say they will “stand up” to countries that “attack” national tech champions, they are defending a services surplus along with the companies that create it. Analysts have noted a shift from protecting factories to protecting platform profits. The incentives are considerable: in 2024, U.S. services exports exceeded $1.15 trillion, with large surpluses found in areas that are easy to offer across borders and hard to remove once they become part of schools and public agencies. The education sector—heavy on software subscriptions, cloud storage, and video—is central to this trade logic. Suppose we want a stable, fair digital education market. In that case, we must view these choices as trade policy, not merely procurement of educational technology.

South Korea shows how platform rules become trade policy

South Korea’s proposed Platform Competition Promotion Act establishes the new framework. The bill draws on the European Union’s Digital Markets Act and would impose preemptive obligations on the largest platforms. U.S. officials and lawmakers have opposed it, claiming the proposal targets American firms. Korean officials argue that the rules are neutral and necessary to curb dominance in search, video, advertising, and app distribution. No matter the perspective, the outcome won’t be determined solely by antitrust experts; it will be negotiated in trade discussions. This situation—domestic digital law as a leverage point in trade—defines digital mercantilism for both nations.

Market data explains the intense political climate. Google and YouTube are dominant players in Korea’s search and social video markets. In music, YouTube Music has overtaken local competitors, a shift aided by broader changes in streaming and by Spotify’s introduction of a free tier in Korea in late 2024. At the same time, Korea boasts strong local platforms in messaging (KakaoTalk) and news, and regulators argue that new rules are essential to protect those services. In essence, Korea reflects the United States: it desires open markets where its firms can succeed globally while maintaining protective regulations to prevent foreign companies from gaining an advantage at home. This similarity is why this case is significant for education systems everywhere.

The education sector is exposed to platform power

Schools rely on a few global platforms for video, storage, communications, and search. This reliance now affects how students learn and the quality of that learning. In the United States, 90% of teens use YouTube, and a substantial number visit daily. OECD evaluations show that educational systems accelerated their shift to digital platforms during and after the pandemic, and have not reverted to previous practices. With such high usage, a platform’s decision to promote or suppress content, modify an API, or raise prices can quickly disrupt lesson plans. When a country with a substantial digital services surplus defends its platform companies internationally, the implications for classrooms are direct: dependency, switching costs, and gradual increases in recurring fees. That’s why we must address digital mercantilism as an issue of education governance, not just a trade issue.

The Korea case also demonstrates the complexity of "local versus global" in education. YouTube's reach in Korea is extensive, yet local platforms still influence daily communication and news. For schools, this mix can either be beneficial—providing global content libraries with local control points—or a drawback if data portability and interoperability are weak. The better question for ministries and districts is not “American or local?” but “What rules make it easy to switch platforms, ensure reliable content discovery, and protect student data?” In a world of digital mercantilism, those regulations are crucial to prevent international business strategies from overshadowing local education objectives.

Policy for a level playing field: reciprocity, portability, and evidence of benefit

First, we need to establish reciprocity tests for platform privileges. If a country blocks, limits, or taxes foreign education platforms in a way that its own firms would resist abroad, access to public contracts and preferred distribution should consequently shrink. Reciprocity is not a tariff; it’s a straightforward standard for how firms can engage with civic institutions like schools and universities. This method recognizes digital mercantilism instead of ignoring it. It sets conditions under which competition is fair enough to benefit learners, not just shareholders. Governments already apply this in finance and telecommunications; education deserves the same approach.

Second, we must ensure real portability and exit options. Districts should be able to migrate lesson libraries, rosters, assessments, and video with minimal costs and downtime. If a platform has market power, it must meet higher standards for open protocols and defined migration paths. Korea's proposal and Europe’s DMA both move in this direction. Still, education ministries need to adapt these ideas into procurement practices: clear data formats in contracts, penalties for failed migration, and service credits when a provider’s design choices create obstacles. With these measures in place, digital mercantilism loses its power, as switching becomes manageable even with one dominant firm.

Third, we should demand proof of benefit for classroom time. Platforms that provide instruction should present independent evidence on learning outcomes tied to use. Suppose a video service is where teens spend hours. In that case, it should demonstrate how recommended learning playlists influence engagement and mastery, not just how ads convert. Education systems can coordinate efforts by sponsoring a small shared lab to conduct rapid evaluations across markets, publishing brief reports, and making the results necessary for contract renewal. This isn’t anti-trade; it promotes learning in a trade-influenced environment. It also addresses a common concern—that new rules will stifle innovation—by linking market access to clear value for students rather than origin or political influence.

Finally, we need to create a narrow pathway for strategic digital content. Sometimes, countries want to support local curriculum materials, language tools, and libraries developed by teachers. This can be achieved through content minimums in public budgets, transparent grants for local creators, and open-source repositories accessible across platforms. The goal isn’t to ban foreign tools but to guarantee that a nation’s cultural and educational resources aren’t excluded or suppressed by global recommendation systems. By doing this, the local content policy fosters competition based on merit rather than hidden protectionism.

We started with $266.8 billion—the U.S. surplus in digitally deliverable services. This figure explains much of today’s policy discussions and the pressure schools face when platforms change. Korea’s situation illustrates that digital regulations have international implications. They create trade issues when affected companies are foreign and become educational issues when those firms are integral to classroom practices. The solution isn’t to choose sides in a national rivalry or wish away digital mercantilism. The solution is to make education procurement and regulation precise: reciprocity for access, portability for exit, and proof of benefit for classroom time. If leaders implement these strategies, teachers will keep their tools, students will continue to progress, and countries can maintain a commitment to both innovation and fairness. If they fail to act, we will keep facing trade conflicts through school operations and platform decisions, and that $266.8 billion will continue to drive these discussions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2023, December 12). Pew survey: YouTube tops teens’ social-media diet, with roughly a sixth using it almost constantly.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2024, October 18). Trade in Services in 2023 and Services Supplied Through Affiliates.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2025). International Services (Expanded Detail).

Brookings Institution. (2025, March 10). Trump’s tech tariffs: From protecting production to protecting Big Tech’s profits.

Brookings Institution. (2025, October 8). Donald Trump’s digital mercantilism.

Chosun Ilbo (English). (2025, May 13). YouTube Music and Spotify overtake local platforms in Korea.

Korea Herald. (2025, August 7). Seoul seeks to ease U.S. concerns about the platform bill’s impact on American firms.

Lawfare. (2025, May 20). South Korea’s digital regulation proposal sparks U.S. pushback.

OECD. (2023, December 13). Digital Education Outlook 2023.

Pew Research Center. (2023, December 11). Teens, social media and technology 2023.

Reuters. (2024, October 9). Spotify starts free streaming option in South Korea.

Reuters. (2025, February 4). OpenAI clinches deal with Kakao… (noting KakaoTalk as Korea’s dominant messaging app).

Statcounter Global Stats. (2025, October). Search Engine Market Share in Republic of Korea.

Statcounter Global Stats. (2025, October). Social Media Percentage Market Share in Republic of Korea.

Tech Policy Press. (2025, August 8). Digital regulation is no longer just domestic policy as Korea and U.S. clash over new law.

Comment