CBDC Privacy and Monetary Sovereignty: Why Rules, Not Code, Will Decide Adoption

Input

Modified

CBDC privacy decides whether people will use digital cash Most countries want CBDCs for sovereignty; the U.S. favors regulated dollar stablecoins Adoption hinges on clear privacy floors and narrowly limited controls—or private dollar stablecoins will dominate

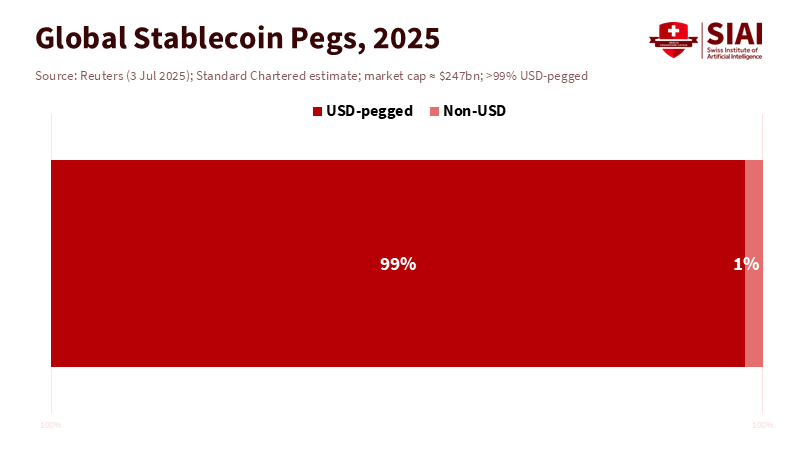

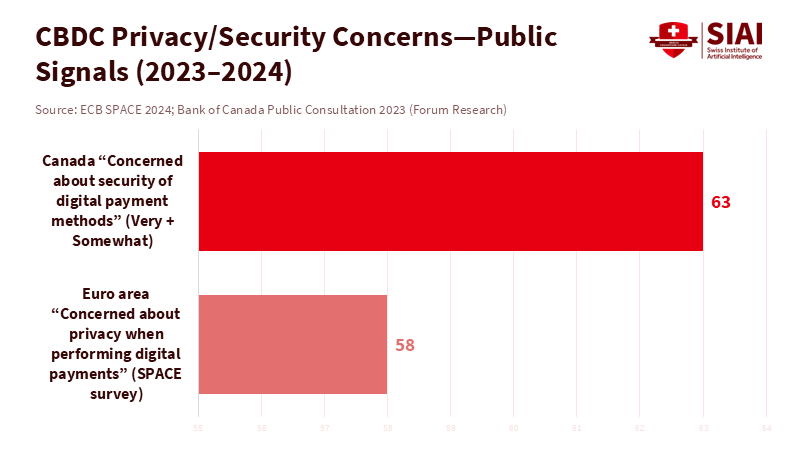

CBDC privacy is now central to the future of money. More than 90% of central banks are exploring or developing a central bank digital currency. Meanwhile, a separate system of private dollars is advancing rapidly. Approximately ninety-nine percent of stablecoin value is tied to the U.S. dollar, and the sector is worth about a quarter-trillion dollars. The difference is striking. Most countries see CBDCs as ways to protect monetary sovereignty and control capital flows. In contrast, the United States is wary of a retail CBDC and is focused on regulating dollar stablecoins. Citizens everywhere are noticing the same thing: if digital cash means constant tracking, they won’t use it. Surveys in Europe and Canada show that privacy is the top concern. Early CBDC launches in Jamaica and Nigeria highlight this point: adoption has been slow, as people fear surveillance or complications. Unless policymakers ensure CBDC privacy is credible, adoption will falter, even as USD stablecoins grow.

CBDC privacy and the sovereignty trade-off

The main policy trade-off is straightforward. CBDC privacy must be strong enough to resemble cash, while sovereignty requires tools to monitor flows and enforce rules. Many governments, especially outside the U.S., view CBDCs as a means to maintain control over money in a world with mobile capital and dollar-pegged tokens. China’s e-CNY exemplifies this view. Its two-tier structure and “controllable anonymity” promise daily privacy but keep identities and flows visible to state actors when certain limits are crossed. This design supports capital management and regulatory oversight within a centralized system. Supporters see this as a necessary response to private systems that could undermine policy. At the same time, critics caution that it incorporates surveillance by default. Both points are valid: CBDCs extend the state’s visibility compared to cash. The policy question is how far that visibility should extend—and who monitors those in charge.

Looking through the lens of sovereignty clarifies why different countries take different approaches. The BIS has warned that widespread use of foreign-currency stablecoins can weaken monetary sovereignty and complicate currency regulation. Emerging markets, dealing with dollarized savings through tokens, view CBDCs as public alternatives that keep seigniorage, data, and policy control local. In Europe, the digital euro is described as a way to protect monetary sovereignty and payment stability against Big Tech wallets and private tokens, with privacy as a key feature. In the U.S., the political mood is moving away from a retail CBDC: the House has passed an “Anti-Surveillance State” bill, and the Federal Reserve is focusing on research without making commitments. This divide is also visible in the language used: freedom and market choice in Washington, versus sovereignty and system safety in Frankfurt, Paris, and many capitals across Asia. This strategic split sets the stage for a prolonged rivalry between public CBDCs and private, mostly dollar, stablecoins.

Stablecoins as America’s ‘free-market’ dollar—and the global response

U.S. policy is leaning toward a regulated stablecoin system instead of a retail CBDC. Dollar-pegged tokens dominate this category, with recent estimates placing the market near $250 billion and transaction volumes in the tens of trillions, as on-chain systems support almost instant settlement and programmable transfers. The Senate’s passage this year of an "Anti-Surveillance State" bill, which aims to protect citizens' privacy in the digital realm, along with major U.S. issuers holding short-term Treasuries, has established a private “digital dollar” framework that relies on money-market-like reserves. This approach reflects American preferences for market solutions and diversity in payment systems. It also expands the dollar’s influence, even where local leaders may prefer otherwise. The reasoning is strong: if stablecoins resemble dollars, people in unstable economies will use them—without needing an embassy.

The international reaction is cautious. The BIS and the ECB warn that foreign-currency stablecoins can lead to capital flight and weaken monetary flows, particularly in emerging markets. Dollarization refers to the process by which a country adopts the US dollar as its official currency or uses it alongside its own currency. Latin America serves as a live case study. Stablecoins already represent significant portions of crypto activity in Argentina and Brazil. In Venezuela, businesses and even the state oil company have turned to USDT due to sanctions and dollar shortages. This is dollarization through apps. It is practical and popular—but it is destabilizing for countries trying to manage their own monetary policies. The policy response is to provide public money with credible CBDC privacy and protections, or to implement strict limits on private tokens. Most governments will likely pursue both strategies. The outcome will depend on whether public options can meet the convenience of private systems without crossing privacy thresholds.

The adoption gap: people will not trade cash for surveillance

CBDC privacy is not just an added feature; it is a fundamental necessity in the digital payment landscape. The ECB’s public consultation found that privacy was the most requested attribute for a digital euro, ahead of speed and cost. A 2024 euro-area consumer study found that 58% expressed concern about privacy in digital payments. Canada’s central bank received the same feedback in its consultation: people worry about losing confidentiality with a state digital currency. Where these fears exist, adoption rates lag. Nigeria’s eNaira remains a small part of currency circulation two years after its launch, despite marketing efforts and policy pushes. Jamaica’s JAM-DEX has faced challenges in attracting merchants and users, with officials noting issues with point-of-sale interactions and customer experience. People may accept bank apps and card networks tracking them; they will reject a CBDC if they believe the state can track every coffee purchase and bus fare.

Design choices can help bridge this gap. India’s retail e-rupee pilot has added offline and programmable features, with usage increasing among participants and banks through 2025. The key is practical privacy: small offline transactions that settle locally, identity checks based on thresholds, and limited data retention. These choices reduce feelings of surveillance without sacrificing compliance for larger, riskier transactions. Where pilots emphasize real-world uses—such as transit, stipends, or campus cards—adoption is quicker because the trade-offs are tangible: tap-to-pay like cash, with cash-like discretion for low-value transactions. This is a promising direction for CBDCs, offering the privacy of cash with the convenience of digital payments. Anything less will make CBDCs seem like just more traceable debit cards, and citizens already have those.

A policy design that can work: privacy floors, programmable ceilings

The way forward is to establish CBDC privacy as a mandatory standard and clarify the tools for sovereignty. A privacy standard means cash-like protections for small-value, everyday transactions—offline if necessary, with keys kept on user devices and no central record, except under narrow, tested circumstances. It also imposes strict limits on what intermediaries and the central bank can access, using cryptographic methods to ensure compliance without mass data collection. Central banks and research partners have identified feasible privacy-enhancing technologies for CBDCs, such as zero-knowledge proofs for sanctions checks and blinded credentials for tiered wallets. This combination can maintain controls on illicit finance while reassuring the public that their digital cash isn’t constantly tracking them.

Programmable ceilings are the counterpart to this. Suppose policymakers want CBDCs to help manage capital flows. In that case, they need to make that clear—and define when limits, delays, or location rules can apply. China’s “controllable anonymity” is a more assertive version of this model: anonymity up to certain limits, with traceability beyond them, along with centralized oversight to enforce targeted restrictions. Europe’s approach is softer—focused on sovereignty and resilience rather than direct capital control—but still considers limits on holdings and offline amounts. The BIS’s vision of a unified ledger promises efficiency gains by bringing public and private money onto shared systems, but it also concentrates governance. The legal structure becomes crucial. Get the rules right, and trust will follow; get them wrong, and adoption will slow while private dollars take over.

What this means for education and policy practice

Education systems influence how societies accept monetary changes. Universities and vocational programs should treat CBDC privacy as a core design and policy topic, not just a side note in fintech courses. Students need to learn how privacy-protecting cryptography works in payments, how monetary sovereignty connects with cross-border wallets, and how to weigh seigniorage and data governance trade-offs. Policy schools should develop clinics that draft example CBDC privacy clauses, simulate capital control situations, and create disclosure frameworks that the average citizen can understand. Business schools should emphasize how regulated stablecoins impact Treasury markets and banking deposits, since this is already happening at scale and will influence corporate treasury decisions and public debt financing.

For administrators in schools and colleges, the immediate operational question is whether and how to accept CBDC or stablecoin payments if they become common for tuition, remittances, or aid distribution. The safest route is to default to public money with privacy features mandated by law, while allowing a controlled pathway from regulated dollar stablecoins for international students and donors. The legal and reputational risks vary by jurisdiction. Still, the main guiding principle is clear: payments should be auditable by institutions without exposing students to unnecessary financial surveillance. This approach aligns institutional trust with student expectations. It preserves opportunities for innovation without turning the bursar into an unwitting surveillance agent.

The initial figures tell a simple story: central banks are taking action, but the public cares most about CBDC privacy, while private dollars rush ahead on open networks. This is not a technology gap. It is a gap in the rules. Suppose digital cash feels like a tracking device. In that case, citizens will prefer cards, apps, or—especially outside the U.S.—dollar stablecoins that are available now. If it feels like cash, they will use it, and governments will keep the monetary tools they need. The choice before us is not CBDC versus freedom. It is whether we can ensure a privacy standard and clear, limited sovereignty tools before the market decides for us. The call to action is clear. Legislators should enact privacy-by-design laws for any CBDC; central banks should publish concrete plans for data minimization; regulators should oversee stablecoins without expecting them to disappear. If we do this, adoption will follow the rules rather than evade them. If not, the future of money will be defined by private code—and linked to someone else’s flag.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aldasoro, I., et al. (2025). Stablecoin growth – policy challenges and approaches. Bank for International Settlements Bulletin No. 108.

Bank for International Settlements. (2025). Annual Economic Report 2025—The next-generation monetary and financial system. Chapter III.

Bank of Canada. (2025). Privacy-Enhancing Technologies for CBDC Solutions. Staff Discussion Paper 2025-1.

Bank of England & HM Treasury. (2023–2024). The digital pound: Consultation and response.

Brookings Institution. (2025). What are stablecoins, and how are they regulated?

Carstens, A., & BIS. (2025, June 24). BIS warns on stablecoins (news coverage). Reuters.

Chainalysis. (2024). The 2024 Geography of Cryptocurrency Report. (Latin America excerpt).

Chu, Y. (2025). Monetary sovereignty and central bank digital currencies: Competing models for future cross-border payment platforms. Global Policy.

Cité de la Banque de France. (2025). Central bank digital currency: the sovereignty challenge. Speech.

European Central Bank. (2021). Results of the public consultation on a digital euro. Press release.

European Central Bank. (2024). Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area.

European Central Bank. (2025, July 28). From hype to hazard: what stablecoins mean for Europe. ECB Blog.

Federal Reserve Board. (2024). Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) (public explainer page).

Harvard International Law Journal. (2022). Laband, J., Evaluating China’s CBDC (e-CNY).

Human Rights Foundation. (2025). CBDC Tracker—Nigeria.

International Monetary Fund. (2024). Central Bank Digital Currency: Progress and Further Considerations. Note 052.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Rey, H. Stablecoins, tokens, and global dominance. Finance & Development.

Jamaica, Bank of. (2025). Annual Report 2024.

Mu, C. (2021–2023). Remarks on “controllable anonymity” (English summaries). DigiChina (Stanford).

NUS Singapore Journal of Legal Studies. (2024). The coming CBDC revolution and the surveillance state. (E-CNY analysis).

Reuters. (2024, Mar. 5). Tether crosses $100 billion in circulation.

Reuters. (2024, Apr. 22). Venezuela to accelerate cryptocurrency shift as oil sanctions return.

Reuters. (2025, Jun. 18). Stablecoins’ market cap surges to record high as U.S. Senate passes bill.

U.S. Congress. (2024–2025). CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act. House Report 118-493.

WEF / McKinsey. (2025). Stablecoins: payments infrastructure for modern finance.

Comment