The end of the factory escalator: why service-led industrialization must carry the next jobs wave

Input

Modified

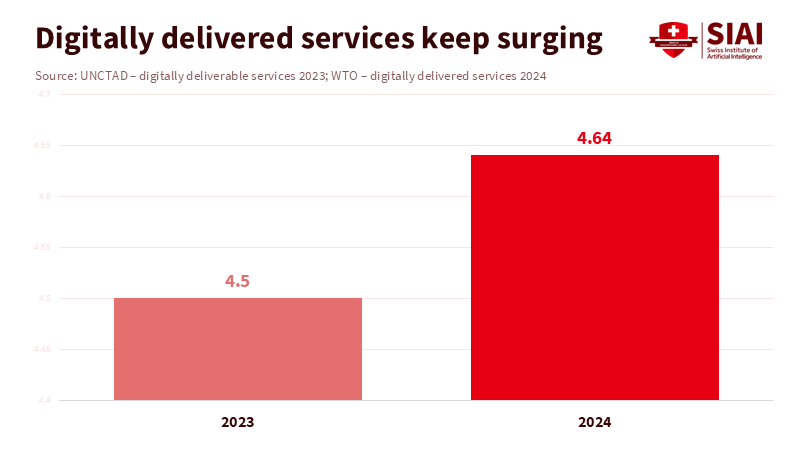

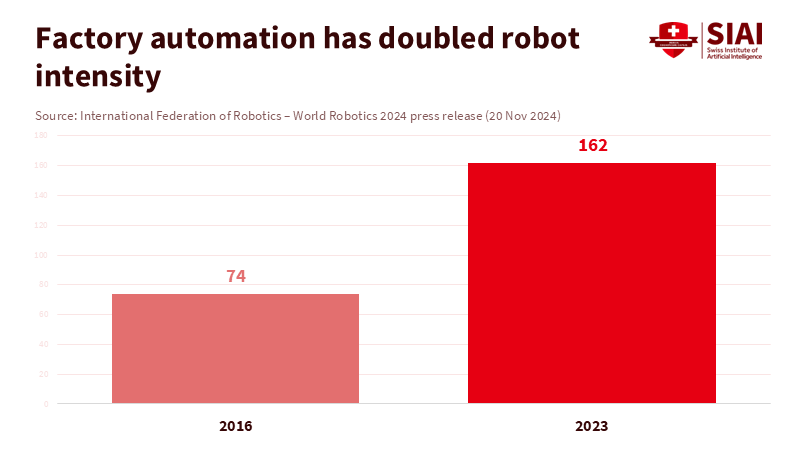

Manufacturing hires fewer people; services now drive job growth Digital services hit $4.25T and robot density doubled, shrinking mid-skill factory roles Pivot to service-led industrialisation with skills, standards, and digital trade rules

In 2023, the world sold US$4.25 trillion worth of services delivered over networks, such as accounting, software, design, finance, and teaching, with no shipping containers in sight. This total grew by 9% over the past year, now accounting for nearly 14 percent of all global trade. Meanwhile, factories continued to install robots at a record pace. Global robot density more than doubled over seven years, while the share of people working in industry continued to decline. The jobs engine has shifted. Many countries still pursue labor-intensive assembly work, as if the old escalator were still operational. It isn’t. Productivity gains and automation mean modern plants hire fewer, but more skilled, workers. The focus now should be on creating an economy where service-led industrialization absorbs workers on a large scale, raises pay, and connects to advanced manufacturing through data, engineering, and after-sales services.

Why service-led industrialization is the next escalator

The traditional method of moving workers from low-productivity farms to labor-intensive factories lifted hundreds of millions of people. However, the dynamics have changed. In OECD economies, manufacturing lost 8.6 million jobs between 2000 and 2018, even as output increased. This trend reflects outsourcing, technology, and energy shocks. In 2023, robot density in factories reached 162 units per 10,000 employees, more than double the levels of 2016. This shift pushes companies to focus on capital and skills over headcount. Simultaneously, global exports of digitally delivered services rose to US$4.25 trillion in 2023, with estimates suggesting they will reach US$4.64 trillion in 2024. This trend is not a temporary deviation but a new reality. The jobs escalator now exists in professional, technical, and digital services closely linked to industry, such as engineering, maintenance, cloud services, logistics, and design. Countries that continue to pursue outdated assembly lines will lose out on where demand and employment are growing the fastest.

Manufacturing has not vanished; it has changed how it hires. In advanced economies, a larger share of factory jobs is high-skilled, while middle-skill roles are decreasing. The OECD notes the rise of high-skill occupations across regions and sectors. Cedefop projects that job creation in high-tech services will exceed that in high-tech manufacturing by more than three times through the 2030s, indicating a promising future for high-skill services. This change isn’t limited to wealthy nations. Indonesia’s experience illustrates this well: the share of manufacturing in its GDP fell from around 32 percent in 2002 to about 19 percent in 2024, alongside layoffs in large apparel and footwear companies. The lesson is clear: policy should regard services as essential, not as a lesser option, and as a driver of structural change that strengthens industrial capacities and absorbs labor.

What the jobs data really shows

Global employment dynamics are undergoing a significant shift from industry to services. According to World Bank and ILO data, industry employment, which includes manufacturing, mining, utilities, and construction, accounted for about 23–24 percent of total jobs in 2023, while services dominated the majority. Even in regions where factories are still increasing output, employment growth is much slower due to the boost in value added per worker from automation. UNIDO estimates reveal that Asia and Oceania accounted for 56.7 percent of global manufacturing value added in 2023, highlighting how output leadership can coexist with slower factory job growth. At the same time, digitally delivered services surged in developing economies, with UNCTAD estimating these exports exceeded US$1 trillion for developing nations in 2023. The world is not simply deindustrializing; it is increasingly service-oriented, integrating code, engineering, and after-sales support into products. Employment follows this trend.

The hiring intensity in manufacturing is also changing due to the pace of automation. The International Federation of Robotics reports record robot installations and a significant rise in worldwide robot density since 2016. China’s situation illustrates this shift: by 2024, it surpassed Germany in robot density and is now among the most automated manufacturing economies. High robot density does not eliminate manufacturing, but alters the mix of skills needed—fewer machine operators and more technicians, software specialists, and process engineers. OECD data show high-skill positions replacing middle-skill roles across various regions, a trend amplified within global value chains where foreign demand supports a growing share of high-skill jobs. This is why treating services as central to industrial strategy is essential; it responds to a labor market that has already evolved.

From factories to platforms: building a skills-first ecosystem for service-led industrialization

The main barrier to job growth in services is not a lack of demand; it is productivity. Services can absorb labor on a larger scale when they become tradable, data-rich, and process-driven. Achieving this requires a focused industrial policy specifically for services. In Europe, leading economists have started advocating for a clear services industrial policy, akin to what manufacturing has long had. They are correct. High-wage, high-productivity services depend on public goods that individual companies tend to underprovide, such as interoperable digital infrastructure, secure data governance, standardized procurement for cloud services and AI, and robust pipelines for technical and professional skills. In practical terms, this means redirecting subsidies from generic tax breaks to investments that lessen fixed entry costs for local providers—from cybersecurity clinics for small and medium-sized enterprises to shared testing centers for AI-enabled services and clean-tech maintenance. A clear services industrial policy is not just a suggestion, but a necessity for the future of the industry.

Education systems must align with the new industrial strategy. The most valuable skill for the next decade will be work-ready competence in data, design, and problem-solving, combined with domain knowledge. This calls for modular qualifications and apprenticeship models that acknowledge skill clusters rather than just narrow job titles. It also requires workforce policies that treat services with the same seriousness as given to factory work: portable benefits, faster recognition of prior learning, and public co-investment in mid-career training with demonstrable wage gains. Evidence from the OECD on the rise of high-skill roles and the decline of physically intensive tasks suggests that well-designed upskilling can transition workers into more resilient roles. However, the supply of training must align with measured demand: procurement contracts, export vouchers, and partnerships that guarantee real projects for newly trained graduates. The government cannot manage service markets down to the smallest detail. Still, it can minimize the risks of initial investments.

Regulation should aim to make services exportable. WTO data shows that the fastest growth in cross-border services is in digital and professional sectors, not tourism. Countries that reduce cross-border barriers—through mutual recognition of professional licenses, compliance with privacy laws for data flows, secure e-invoicing, and streamlined VAT regulations for digital services—can boost both productivity and employment. The reward is not just white-collar jobs. A service-led industrial economy also creates hands-on, local jobs, such as installing and maintaining renewable energy systems, retrofitting, conducting energy audits, optimizing logistics, servicing medical devices, and using robotics for industrial cleaning. Policies that standardize workflows and quality in these areas can enhance productivity and wages. When procurement prioritizes service performance—such as uptime, response times, and efficiency—rather than cost alone, companies will invest in training and software, thereby improving job quality.

Vietnam’s pivot—and a blueprint for others

If Southeast Asia serves as a test case, Vietnam is leading the way. The country is advancing from assembly to chips, AI, and digital platforms. Investors have committed billions to advanced packaging and testing, with major global companies expanding their factories and supply chains in Vietnam. Importantly, Hanoi is not viewing this just as a manufacturing story. The government aims to train 50,000 semiconductor engineers by 2030, supports a national innovation network, speeds up the rollout of 5G, and has enacted a Digital Technology Industry Law to nurture domestic tech firms. The aim is to cultivate a workforce that not only assembles, but also designs, tests, services, and exports. This represents service-led industrialization by design: training for integrated circuit designers and test engineers, developing EDA, verification, and failure-analysis services, and establishing legal frameworks for data, arbitration, and intellectual property to enable higher-value services to grow.

Vietnam’s approach also acknowledges the importance of policy sequencing. First, develop capacity in tradable services connected to manufacturing—such as design, logistics, quality, and cybersecurity—then build up. The government cannot simply create a foundry, but it can strengthen the services infrastructure that every foundry relies on. This is why Hanoi’s collaborations with tool vendors and global universities are as crucial as tax incentives. At the same time, China is promoting service-oriented manufacturing nationwide, integrating advanced manufacturing with modern services by 2028. The global trend is clear: richer services around industry lead to better jobs. For countries in South or Southeast Asia concerned about losing the manufacturing race, the solution is not to cut wages. Instead, it is to enhance services that enable firms to produce, transport, and support complex products.

A practical path to service-led industrialization

Policymakers, educators, and employers can take immediate action. Set specific service productivity goals in national plans, such as tasks per hour in logistics, first-time fix rates in energy maintenance, and days to contract for cross-border professional work, tying public funding to improvements. Use public procurement to create strong demand for local suppliers in cloud, cybersecurity, engineering services, and digital health, including milestone payments for measurable outcomes. Create skill compacts that guarantee apprenticeships and mid-career training in exchange for tax credits, concentrating on jobs where wage increases are evident: data technicians in hospitals, building energy auditors, industrial maintenance specialists, and technical account managers for export SMEs. Lastly, coordinate with trade ministries to clear obstacles for digital exports by recognizing credentials, enabling privacy-compliant data flows, and simplifying VAT for cross-border services. If this is done, the jobs will follow. The data already indicate the trend: services trade is rising, factory automation is accelerating, and high-skill jobs are growing.

Pushback should be expected. Some may argue that only manufacturing can create mass employment. That may have been true in the past, but it no longer captures the whole picture. Others might worry that service jobs are "flimsy." They do not have to be. When services are standardized, tech-enabled, and exportable, productivity increases and wages rise. Europe's discussion of a services-first industrial policy is not a retreat from industry; it is a way to maintain industrial competitiveness by investing in services that enhance factory productivity. The same reasoning applies in Jakarta, Lagos, Dhaka, and Mexico City. We should not abandon factories; instead, we should surround them with design, data, maintenance, finance, and global distribution. That is how we rebuild the escalator.

The critical statistic deserves emphasis: US$4.25 trillion in digitally delivered services in 2023, projected to rise again in 2024; robot density in factories more than doubling in seven years; manufacturing output increasing, yet with far fewer middle-skill roles. The jobs escalator has changed levels. The task now is to guide workers toward service-led industrialization that connects with advanced industry and expands inclusion. By building the services infrastructure—skills, standards, data regulations, and procurement—the economy will generate the roles that mass manufacturing once filled. Ignoring this shift will lead countries to chase a dwindling number of factory jobs while overlooking the opportunities next door. The aim is not to reject manufacturing in favor of services. Instead, we must embrace services to advance industrialization, and we must do so urgently, as the hiring patterns of the coming decade are already being established.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Dani Rodrik (2025, October 15). Why Europe Needs an Industrial Policy for Services. Social Europe.

International Federation of Robotics (2024, November 20). Global factory robot density doubled in 7 years.

International Labour Organization (2023). World Employment and Social Outlook (various datasets via ILOSTAT/WDI).

Le Monde (2024, September 23). The significant decline of European industry.

Reuters (2024, November 12). Vietnam expands chip packaging footprint as investors reduce ties to China.

VnExpress (2025, November 12). Vietnam to have 50,000 semiconductor engineers by 2030.

UNCTAD (2024, December 6). Developing economies surpass $1 trillion in digitally deliverable services exports.

UNIDO (2024). International Yearbook of Industrial Statistics – Asia and Oceania factsheet.

WTO (2024, April 12). Ralph Ossa, Trade growth likely to pick up in 2024 in spite of… (WTO blog).

WTO (2025, April 14). Global Trade Outlook 2025.

OECD (2023, October 31). The Future of Rural Manufacturing.

OECD (2024, November 13). Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2024.

APO (2024, September). Global Perspectives on Premature Deindustrialization.

China Daily (2025, October 14). Manufacturing, services to further integrate (service-oriented manufacturing plan through 2028).

Financial Times (2025, September). Why a commodities boom is not lifting Indonesia’s economy.

Comment