How North Korea-Russia Military Help is Changing Security in Eurasia

Input

Modified

Pyongyang supplies shells and labor to Russia Sanctions erode; nuclear recognition pressure rises Choke arms-for-oil routes; align allies

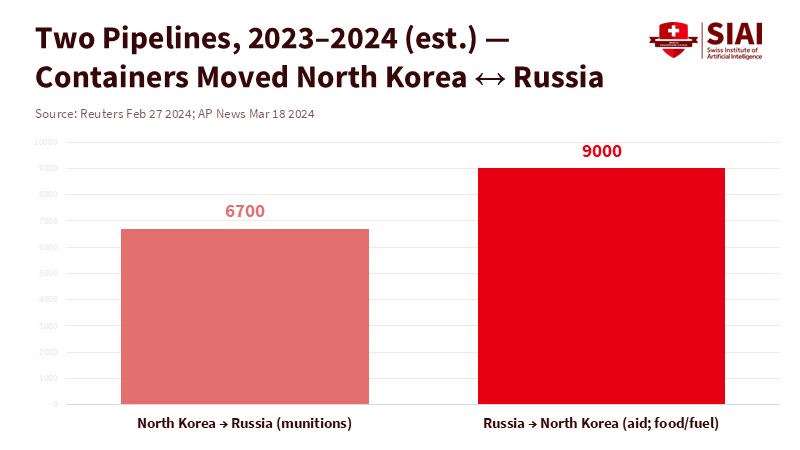

The military support between North Korea and Russia isn't just a minor issue in the Ukraine war anymore. It's actually shaping things in the region. Since around the middle of 2023, North Korea has sent roughly 6,700 containers full of ammunition to Russia. In return, Russia has sent about 9,000 containers, mostly food, to help stabilize prices in North Korea. This isn't just a symbolic exchange. According to analyses from the U.S. and Ukraine, Russia has fired North Korean short-range ballistic missiles in several attacks, including around Kharkiv. These shipments mean North Korea has become a key supplier in a war where resources are being depleted, and it helps Russia keep its own production going. For North Korea, the advantages are oil, food, and increased influence. Doing so lessens their reliance on China, provides them with some protection against the U.N. Security Council's gridlock, and makes them a player everyone has to consider when planning in Eurasia. This military cooperation between North Korea and Russia has brought about a noticeable, measurable change that will be difficult to reverse.

North Korea-Russia Military Help is Changing Deterrence

The main point is legal and political, not just about weapons. In June 2024, Putin and Kim Jong Un signed an agreement. They promised to help each other militarily if either enters a war from an armed attack. This moves their partnership from informal to formal: a joint defense promise. It also creates opportunities to collaborate in fields such as space and nuclear energy. These have long been off-limits by the U.N. The wording does not require daily cooperation to change how things work. Instead, it provides North Korea with protection against isolation and gives Moscow a steady ammunition partner.

The political protection matters because it's getting harder to enforce rules. In March 2024, Russia stopped the renewal of the U.N. panel of experts that had been watching sanctions on North Korea for 15 years. That didn't lift the sanctions, but it removed a way to publicly track violations—like oil transfers between ships or workers overseas. The veto suggested that countries don't agree on the basics of stopping the spread of weapons, right when there was more information about North Korea-Russia transfers. The result is strange: the rules are still there, but the desire and ability to enforce them have weakened. That's where the military help between North Korea and Russia has grown.

People and Supplies: Two Ways, One Plan

The first way is through people. South Korea’s intel group told lawmakers North Korea planned to send 6,000 construction and demining workers to Russia’s Kursk region by July or August. Earlier, they said thousands of North Korean workers were already in Russia at construction sites, earning about $800 a month. These workers, whether called civilians or military, do the same thing. They free up Russian workers, send money home, and make it easy to hide cooperation between the two nations. It is not outright mobilization, but it is a reliable capability. In a war for resources, that matters.

The second way is through ammunition. By February 2024, South Korea’s defense chief said that North Korea had sent about 6,700 containers of ammo to Russia, while U.S. sources estimated the total would exceed 10,000 containers by late winter. On the battlefield, U.S. and Ukrainian experts found fragments of North Korean KN-23/24-class missiles used by Russia, and Ukrainian sources estimated about 100 had been fired by early 2025. The quality of these missiles is as important as their quantity. Short-range ballistic missiles strain Ukrainian air defenses and force difficult choices on what to intercept. Artillery shells let Russia keep up its heavy fire while shifting factories to build better systems. In short, North Korean support directly aligns with Russia's wartime strategy.

What does North Korea get in return? Reports say food and fuel have been returned. Investigations, including one linked to the BBC, found that Russia likely supplied North Korea with more than 1 million barrels of oil in 2024, far more than the U.N. allows. Oil and basic goods are essential for keeping prices steady at home and for maintaining North Korean factories running, especially those that make ammunition. They also let North Korea protect itself from China. China still makes up almost all of North Korea's trade, close to 98 percent in 2023, but the Russia route reduces the risk of relying on just one country and increases North Korea's ability to get better deals with all its allies. The protection is small, but in critical situations, even small differences can change decisions.

The Risk of Recognizing North Korea's Nuclear Status

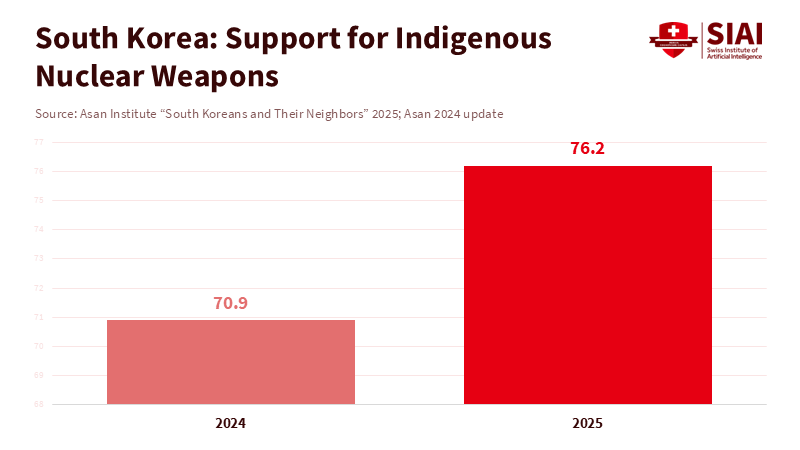

The change in alliance has nuclear implications. As Russia depends on North Korea and protects it at the U.N., the chances increase that North Korea will be seen as a permanent nuclear power. This recognition can happen without anyone saying it directly. It occurs when big countries make deals that involve North Korea's weapons as a given while discussing other things. Experts already see this happening in Washington's discussions. Some suggest a freeze-for-freeze or sanctions-for-cap approach, which would trade practical limitations for lower risk. Others worry that any move that seems like acceptance will make countries like South Korea and Japan want to develop their own nuclear weapons. The more normal the military help between North Korea and Russia seems, the more this pressure builds—and the more realistic a freeze looks to people trying to find a solution.

Public opinion has shifted. In South Korea, support for having their own nuclear weapons has risen from the high 60s/low 70s in recent years to a record 76.2 percent in 2025, according to a recent survey. This isn't a minority opinion. It's now a mainstream view that crosses party lines and age groups. Japan is restricted by its laws and culture, but the conversation is no longer off-limits. When a senior official mentioned nuclear sharing in late 2025, the government reaffirmed its non-nuclear stance and rejected the idea—but the fact that the conversation took place shows a shift. If the U.S. starts to accept North Korea's nuclear status, even without saying it, South Korea's and Japan's thinking will lean more towards protecting themselves, whether by improving missile defenses and conventional attacks or, eventually, considering more drastic options.

There's also a back-and-forth happening on the battlefield. Claims from Ukraine, supported by assessments from the U.S. and South Korea, suggest that Russia's use of North Korean short-range ballistic missiles is helping North Korea learn in real time about things like accuracy and reliability. That's a real issue for Northeast Asia. Each improvement in North Korea's missile capabilities makes it better at overwhelming defenses in the early hours of a conflict. Added to the Russia-North Korea agreement, these improvements mean that bad decisions in a crisis could have more severe consequences and less time to react. The concern is this: the more normal the military cooperation between North Korea and Russia becomes, the more neighboring countries will feel the need to strengthen their defenses, and the harder it will be for anyone to back down.

What Teachers and Leaders Need To Do

The first thing is to be clear. The military cooperation between North Korea and Russia is the result of several issues converging, not just smuggling. Teachers in policy schools and military training programs should explain it like that: as two countries' industries and supply lines joining together under a formal agreement. Course topics should show how ammunition in containers, workers overseas, and oil transfers work together to create strength. Students should run practice scenarios: what happens if the Russia route doubles in volume, if China goes from tolerating it to actively supporting it, or if Ukraine's ability to strike back falls by a third. Having clear models prevents unrealistic thoughts. They also prepare future leaders to address the problem on a large scale.

The second thing is to make the solutions to it seem routine. Sanctions are most effective when they are consistent, specific, and built over time. The United Kingdom’s actions against Russian and North Korean groups showed how to target the key points—ports, fuel companies, and go-betweens—that enable these shipments. The U.S. and the European Union have done the same against Russia's unofficial fleet and financial routes. Teachers should encourage students to come up with real ways to ensure people follow the rules: computer programs that flag ammunition loads, shipping insurance rules that punish routes that avoid sanctions, and automatic punishments for train companies that move suspicious cargo. Leaders should include these within a broader framework to ensure enforcement stability. This is not exciting, but Third, change from only thinking about North Korea to thinking about North Korea and Russia. That means linking protecting Ukraine with reassuring countries in Northeast Asia. South Korea's message—after the agreement—that it would consider sending arms to Ukraine if Russia goes too far shows the right way to think: connect reactions across different areas, so Russia can't have peace in one location while causing problems in another. For the U.S., that means continuing to help Ukraine, visibly improving missile defenses in Korea and Japan, and working more closely to treat Europe and Asia as a single security issue. For the European Union, it means punishing the points that move Russian oil to North Korea in exchange for ammunition, while increasing their help to South Korea and Japan on shipping and preventing transfers. For Japan, it means improving its ability to strike back within its laws and working more closely on defense plans.

Finally, invest in people who can understand this problem without any false ideas. Universities should grow programs that combine shipping law, shipping insurance, intelligence, and East Asian security studies. Teacher programs for civics and economics should include topics on how supply lines and sanctions affect war. Education departments can pay for teaching materials that guide students through a container from a North Korean port to a Russian train station, and then show how spending on interceptors in Ukraine changes if a missile with better guidance appears elsewhere. This is not just for a few people. Everyone needs to understand this now that conflicts are connected.

The reason to act comes back to the beginning information. North Korea's 6,700 containers going out and Russia's 9,000 coming back show that this is a cycle, not just a one-time event. The agreement indicates that the cycle is protected by law. The U.N. veto shows that oversight is weaker. The missile pieces show that they're learning on the battlefield. If we let the military help between North Korea and Russia take care of itself, we'll end up seeing more of all four of these things. The option is simple: make enforcement constant; cut off the oil-for-arms routes; keep Ukraine armed enough to make Russia pay a higher price; and stabilize Northeast Asia so that worry doesn't encourage a nuclear buildup. If we do that, the cycle will slow down. If we don't, recognition—whether said or unsaid—will spread, and the idea of building nuclear weapons in South Korea and Japan will become official policy. That's the way to a more fragile Eurasia. We don't want to learn that lesson again.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. “North Korea may send military construction workers to Russia as early as July or August.” June 2025.

Arms Control Association. “North Korea, Russia Strengthen Military Ties.” Arms Control Today, July/August 2024.

Asan Institute for Policy Studies. South Koreans and Nuclear Weapons: 2025 Public Opinion Survey. 2025.

BBC / Open Source Centre. “Refined Tastes: Russian Oil Deliveries to Pyongyang.” 22 November 2024.

Beyond Parallel / CSIS. “Major Munitions Transfers from North Korea to Russia.” 28 February 2024.

Council on Foreign Relations. “Understanding the China–North Korea Relationship.” Backgrounder, 2023–2024 update.

Defense Intelligence Agency (U.S.). “Enabling Russian Missile Strikes Against Ukraine.” Unclassified summary, 30 May 2024.

Government of the United Kingdom, Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. “UK and partners target Russia-DPRK ‘arms-for-oil’ trade with new sanctions.” 17 May 2024.

Reuters (Michelle Nichols). “Russia blocks renewal of North Korea sanctions monitors.” 28 March 2024.

Reuters (Hyonhee Shin). “North Korea has sent 6,700 containers of munitions to Russia, South Korea says.” 27 February 2024.

Reuters (Kyiv/Defense). “Debris analysis shows Russia using North Korean missiles in Ukraine, U.S. military says.” 30 May 2024.

Reuters (James Pearson et al.). “Ukraine sees marked improvement in accuracy of Russia’s North Korean missiles.” 6 February 2025.

The Straits Times. “Thousands of North Korean workers sent to Russian construction sites: Seoul.” 10 February 2025.

War on the Rocks. “Negotiating with North Korea in the Shadow of Great Power Rivalry.” 2 October 2025.

Comment