Growth First, Promises Later: Why More Welfare Won’t Fix East Asia’s Baby Problem

Input

Modified

Skip Europe’s welfare playbook—it didn’t lift births Lead with jobs: housing, productivity, youth careers Keep supports targeted; don’t build a giant state

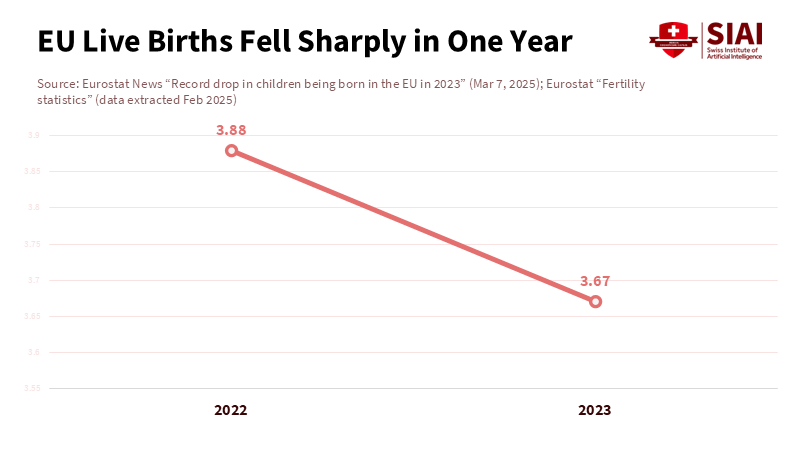

Here’s the thing: In 2023, the European Union’s birth rate hit a record low of 1.38 babies per woman, down from 1.46 the year before. Japan’s even lower at 1.20, and Tokyo’s down to 0.99! If throwing money at the problem actually worked, Europe and Japan wouldn’t be in this mess. They’ve been beefing up social programs for ages, but birth rates keep dropping, and growth is slow. This is important for East Asia. Some say that building bigger welfare states will create safety nets to boost birth rates. But Europe and Japan’s stories tell us that just handing out more benefits hasn’t turned things around. A better idea for East Asia is to focus on jobs that pay well, create opportunities, and make family life more affordable by fixing problems like housing. Handing out cash that workers can’t even afford to pay for won’t cut it. The message is clear: Without jobs and growth, those safety nets will only drag you down.

Some say that East Asia’s old way of doing things didn’t adequately value social support. They think more handouts will jump-start the economy and help parents. But Europe’s been there, done that. The EU spent almost 20% of its money on social programs in 2023. Still, young people can’t find jobs, birth rates are dropping, and growth isn’t great. The problem is bigger than just money. As populations get older, there are fewer workers to support retirees. Handouts can help a little, but they don’t fix the real problems: jobs, productivity, and housing. East Asia shouldn’t repeat the same mistake. It should create a system that makes it easier to start a family by lowering home costs, providing good jobs, and boosting lifetime earnings.

What Europe and Japan Can Teach Us

Europe’s been trying this for years. Social spending rose, but birth rates fell. Germany, Austria, and Estonia now have really low birth rates. People are also having kids later in life, which means fewer prominent families, even when they want them. It can barely grow. Central banks say that without more growth, Europe’s social programs could go bankrupt. Just giving out money didn’t fix the growth problem or make people want to be in a similar boat to Japan. People have jobs, but birth rates are still low. The problem isn’t jobs; it’s wages, costs, and time. If fewer people are working and starting a family is expensive, good job numbers won’t lead to more babies. The World Bank warns that aging could significantly shrink the workforce by 2060, leaving too few workers to support too many older people. Handouts can’t fix that. Growth and productivity need to step up – fast.

Some argue that Europe’s programs still leave young people behind. Studies show they face exclusion and struggle to find good entry-level jobs. Low wages and a lack of affordable housing make things worse. A bigger handout won’t fix these problems. They’re signs of issues in housing, training, and local development. An Asian welfare state that makes the same mistakes will get the same results: temporary relief without any real change.

Welfare Isn’t a Magic Bullet

The idea behind a bigger Asian welfare state is simple: Lower the risks for families, boost spending today, and hopefully, more babies will come tomorrow. But the numbers don’t back it up. Studies show that even countries that spend a ton of money haven’t avoided falling. In 2023, the EU recorded the largest-ever drop in births. Very recorded. Even countries like France and Sweden, which are known for their family policies, are seeing birth rates decline. Handouts might change when people have kids, but they haven’t led families to have more kids over time. Why? There are all kinds of reasons, and money can’t solve them all. Housing eats up an ever-larger share of people’s income. Young adults have a tough time moving out, settling down, and having kids. Strict mortgage rules, a lack of land, and expensive rental markets push people to start families later. As a result, there are fewer babies. Childcare help can make a difference, but if homes near work are too expensive, parents will face long commutes, stress, and fewer children than they want. East Asia’s big cities face the same problems – but even worse. Building a bigger welfare state on top of these housing problems would be a waste of money.

There’s also the growth factor. Spending a lot of money on social programs when the economy is slow can lead to more taxes, less investment, and fewer good jobs. As populations age, pensions and healthcare consume most of the budget, leaving less money for drivers of growth, like research, education, and infrastructure. Sweden’s experience with privatizing some welfare services is another warning: handing services over to private companies without addressing underlying problems can make things worse. The right move isn’t to cut services or privatize everything – it’s to target the right areas and build from there.

Jobs First, Welfare Later

So, what’s the answer? East Asia needs a plan to boost wages and make family life more affordable. First, create more housing near jobs. Loosen up the rules about where you can build near train stations, use new building methods, and make it easier to redevelop old buildings. Europe’s mistake was not doing this, which led to young people facing high rents and delaying the start of families. A real Asian welfare state would start here – not with just handouts, but with creating housing that lowers costs and provides more room for kids.

Second, invest in things that boost productivity. Studies show that European countries spend almost a quarter of their budgets on social programs. That takes away from other things. The answer isn’t to get rid of safety nets, but to keep them steady while shifting money to investments, clean energy, job skills, and local manufacturing. East Asia can be a leader with policies that encourage high-productivity businesses. Jobs are important because they give people confidence and generate tax money.

Third, expand the labor supply. Experts say that aging will lead to more elderly people, depending on each worker. East Asia should encourage more women to work and people to retire later. Japan shows that these can work, but wages need to go up. Selective immigration can help fill gaps.

Fourth, focus on the biggest impacts: early childhood, parental leave, and housing. Studies suggest that handouts can change when people have kids, childcare, and predictable part-time options as careers ramp back up. Simple programs such as credits, leave, and childcare are more effective than stacks of transfers.

Finally, offer real jobs for young people. Stop pushing internships that don’t lead anywhere. Instead, fund training programs, tie wages to skills, and ensure those skills can be used across different companies. Young people who drift are a loss. A jobs-first approach puts families where the growth happens and gives them reasons to stay.

Answering the Other Side’s Argument

Those who want a bigger Asian welfare state will make three points. First, they will say that East Asia’s old way of doing things hurts spending, so more welfare is needed to boost demand. The opposite is true. Europe shows that you can have high welfare spending and still have weak growth when housing is expensive and taxes are high. Handouts without fixing the supply are a rush. To boost spending, you need to raise wages and cut costs.

Second, they will argue that without stronger safety nets, elderly poverty will grow and fewer women will work. That’s possible. But how you spend it is what matters. Much of it is absorbed by stuff that helps those who need it- child care, transportation, and housing near work.

Third, some will say that privatization fixes the problems of quality and cost. Sweden’s experience says otherwise. Private systems without rules create waste. What Asia should not do is believe that change means success. The evidence supports a jobs-first strategy. Agencies are not showing significant growth even after substantial welfare payments. Japan’s birth rate is dismal due to employment there. It does not mean that systems are poor. Asia’s success has always been in building new stuff. It should copy that to take the burden of having families off.

Look back at the numbers: Europe at 1.38, Japan at 1.20. These aren’t because of a lack of love. They are strategy failures. An Asia with more monetary support may buy calm, but won’t revive. Asia needs something that makes young households believe in homes, jobs, and time-saving solutions. When societies of old sought to save costs. Asia does what Europe did; it will have trouble. Make a better place where you can grow.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

European Central Bank (Lagarde speech, coverage). “Welfare state at risk unless Europe halts decline in growth.” Financial Times, June 2024.

Eurostat. “Record drop in children being born in the EU in 2023.” Eurostat News, March 7, 2025.

Eurostat. “Unemployment statistics.” Statistics Explained, accessed December 2025.

International Monetary Fund. Europe Regional Economic Outlook, October 2024.

International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Update, July 2024.

Japan—OECD. Employment Outlook 2024: Country Note (Japan), June 2024.

Macrotrends. “Japan Fertility Rate (1950–2025).” Accessed December 2025.

Nippon.com. “Japan’s Fertility Rate Drops to New Record Low.” June 12, 2024.

OECD. “Declining fertility rates put prosperity of future generations at risk.” Press release, June 20, 2024.

OECD. “Expenditure for Social Purposes—Compare your country.” Accessed December 2025.

OECD. “Public social spending as share of GDP (SOCX).” Data Explorer, accessed December 2025.

OECD. The rise and fall of public social spending with the COVID-19 pandemic. January 2023.

OECD. “Social expenditure dashboard.” Accessed December 2025.

OECD. “Society at a Glance 2024—Fertility trends across the OECD.” Accessed December 2025.

Social Europe. “How Sweden’s Welfare Experiment Became a Warning to Europe.” May 7, 2025.

The Guardian. “EU to crack down on unpaid internships ‘exploiting despair of young people’.” March 20, 2024.

The Guardian. “Young people are the big losers in Europe’s dysfunctional housing system.” December 17, 2025.

World Bank. “GDP per capita growth (annual %)—European Union.” Accessed December 2025.

Youth Forum (European Youth Forum). Excluding Youth: A Threat to Our Future, 2016; “European welfare states are failing young people,” 2016.

Comment