Saving Credit Lines: Why Fixing Banks Can Be Better Than Just Giving Money to Businesses

Input

Modified

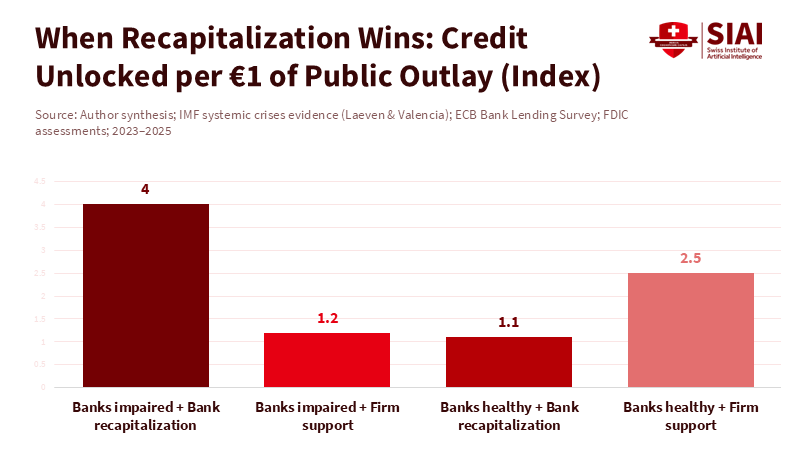

Bank recapitalization can protect Main Street faster than broad firm subsidies in crises It works best when credit supply is impaired, banks are viable, and bail-ins are credible Diagnose the bottleneck; if banks are the constraint, recapitalize first to crowd in private lending

When things get tough, governments have to make a hard choice: help big banks or help regular folks. People often want to just give money to businesses. But sometimes, putting money into banks is the smarter move, and here’s why. Since 1970, governments around the world have dealt with 151 major banking crises. It usually costs a lot – around 8% of a country’s money – because if the credit system breaks down, it hurts everyone. In 2023, the United States protected people who had over-insured amounts at two banks that failed. Doing that will cost about $16.7 billion, which the other banks will have to pay. It wasn’t just a random number; it was a move to protect the payment system and stop the problem from spreading. So, it’s not about choosing banks or people. It’s about figuring out how to get money flowing again at the lowest cost. And sometimes, fixing the banks is cheaper, quicker, and fairer.

When to Fix Banks Instead of Bailing Out Companies

The important thing to save is whatever is blocking the flow of money. If banks are doing okay but don’t have enough money, every dollar the government puts in can free up a lot more in loans. We’ve seen this work before. A study about the U.S. The Capital Purchase Program showed that when banks were stabilized, more jobs were created and fewer businesses went bankrupt in those areas. This happened because stronger banks could lend more easily, which helped the economy. So, if banks are solid but just need more money, and if businesses still want to borrow, fixing the banks can help a lot faster and in more places than just giving grants or loans to individual companies.

Recent problems have shown that banks can collapse quickly if people withdraw their money all at once. In March–May 2023, some banks had to be bailed out because they didn’t have enough cash, and too many customers were withdrawing money at once. Regulators have learned a fast lesson: banks need to have plenty of money on hand and be closely monitored to protect the economy. If banks don’t have enough money saved and people start to panic, helping banks can prevent larger losses than just helping businesses one by one. That’s the main reason why fixing banks might be better than just giving money to companies.

Signs That Fixing Banks Will Help

Before deciding to fix the banks, policymakers should look for some clear signs. First, banks should be making it hard to get loans because they’re struggling, not because businesses don’t want to borrow. In late 2023, banks in Europe made it harder for companies to obtain loans, and this remained the case in 2024–2025. When banks are the reason it’s hard to get loans, helping them makes a bigger difference. In those situations, fixing the banks makes it more likely that good businesses will get the loans they need.

Second, lending should be declining more than expected due to the economy. Data from 2022–2023 shows that business loan activity slowed more than usual during the economic slowdown. That suggests that banks have problems with money and risk, not just that businesses don’t want to borrow. Also, the issues of 2023 showed that if banks aren’t careful with interest rates and have too many deposits from the same people, they can get into trouble quickly. If the banking system is the problem, then fixing it is the best way to help.

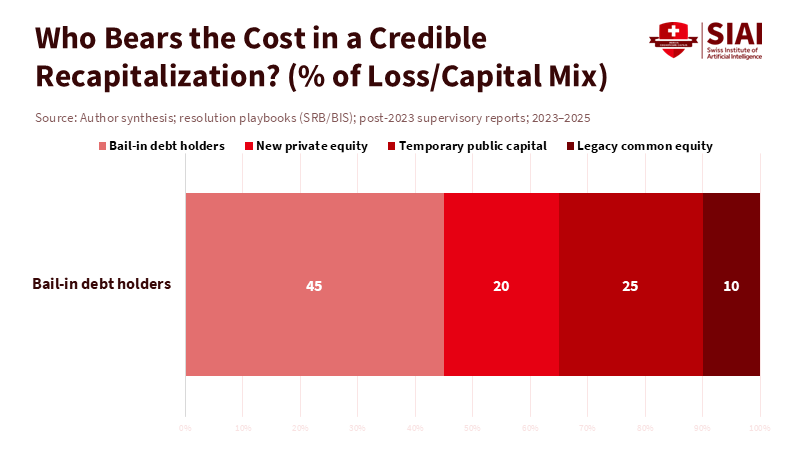

Third, the rules governing failing banks must be strong enough to prevent banks from taking on too much risk. The bank failures in 2023 were costly – for example, the First Republic failure cost the U.S. insurance fund about $15.6 billion, and the Signature failure cost about $2.4–$2.5 billion. But things would have been worse if nothing had been done. If the rules for handling failing banks work well, fixing them can attract private capital and shorten the economic downturn. But if those rules are weak, fixing the banks might just reward bad behavior instead of fixing the credit system.

How to Fix Banks to Attract Private Money

How banks are fixed makes a big difference in whether it helps regular people or just saves the banks themselves. First, the government should offer to put money in at a price that attracts private investors. This shows confidence and keeps the government’s costs down. International rules governing bank money provide a framework, and recent reviews stress the need for supervision, risk management, and the completion of changes initiated after the last crisis. When banks follow those rules and are well managed, fixing them is more likely to get lending going again rather than just paying for past mistakes.

Second, the rules should connect the money to promises to lend, without forcing banks to make risky loans. In the past, programs have tied money to the public and monitored lending plans. The goal isn’t strict limits; it’s making sure that good businesses can get the money they need to operate. Research after 2008 showed that when banks got money, hiring improved and bankruptcy rates fell in those areas. That’s the goal: clear rules, strong oversight, and ways for banks to return to being fully private.

Third, the plan should include quickly shutting down banks that can’t survive and making investors pay for their losses. European and global regulators have learned important lessons from 2023: align rules on cash and interest-rate risk with the speed of digital withdrawals; test assumptions about how quickly deposits can disappear; and ensure that banks can be shut down if necessary. With those safeguards in place, fixing good banks isn’t a handout – it’s a quick way to go from panic back to regular lending.

What This Means for Schools, Cities, and Small Businesses

For schools and administrators, it’s simple: credit helps cover salaries, fees, construction, and vendor costs. When a local bank struggles, schools that depend on tuition, city partners, and small suppliers feel it right away. In those cases, fixing community and regional banks helps quickly and broadly, instead of just giving subsidies to individual companies. It prevents layoffs, keeps things running, and keeps credit lines open. The goal isn’t to protect shareholders; it’s to stop a cash problem from becoming a learning problem.

For small businesses, how help is given matters. Giving broad support to businesses can be slow or poorly targeted. It can also keep weak businesses alive, which prevents good borrowers from getting loans. Research from before and after the pandemic warns that giving money and guarantees without good targeting can prop up weak businesses. New research even shows that the number of weak companies didn’t necessarily increase during the pandemic, where support was targeted and temporary. So, if tight credit is because of weak banks, fix the banks. If weak businesses are the problem, target the help better, don’t loosen capital rules.

Addressing Criticisms

One concern is that fixing banks rewards bad behavior. Critics say that fixing banks rewards risk-taking and sets up the next crisis. That’s a real risk, which is why it should be done with strict rules: requiring investors to pay for losses, changing management, clawing back bonuses, and limiting the government's involvement. Recent reviews emphasize these points and call for stronger management and interest-rate risk controls. If done this way, fixing banks isn’t a reward; it’s a restructuring plan with consequences.

Another concern is that giving money to businesses has a bigger impact. In some cases, that’s true. If banks are healthy and lending is flowing, granting wage subsidies can keep workers and businesses together at a lower cost. But when banks are the problem, pouring money into businesses without fixing the banks doesn’t work well. Tight credit standards and loan growth that’s lower than the economy suggests are the warning signs. That’s when fixing the banks first is the efficient choice.

A third criticism is the cost. Fixing banks can be expensive. But the real question is what would happen if credit dried up. The global data on banking crises reminds us that delays increase costs. Acting early and with a good plan reduces long-term damage compared to just trying to fix things one company at a time. And when losses from protecting depositors have to be repaid – as in the 2023 U.S. special assessment – private contributors share the cost.

Policymakers should understand in advance how much their economies depend on credit. Where regional banks finance many small businesses, schools, and city projects, the government should have a plan to fix banks through strict loss-sharing and quick shutdowns. Regulators should test banks under scenarios where people withdraw their money quickly, as we saw in 2023. Schools and local governments should have backup credit lines with multiple banks and set rules that activate if a bank weakens. The goal is to keep classrooms open, paychecks on time, and local businesses running during tough times.

How to Handle the Next Crisis

Start by figuring out what’s wrong. If credit standards are tight because banks are struggling, and businesses want to borrow, fix the banks first by strengthening management and a plan to return them to private ownership. If banks are fine but businesses are struggling, provide targeted support with time limits and productivity requirements. Have both options ready, but choose the one that fixes the problem. The data from 2023–2025 supports this rule. Banks’ success depends on both money and supervision; when that weakens, the economy suffers quickly. Having plans to fix banks that attract private money, limit bad behavior, and restore credit is the best way to protect regular people.

Financial crises are costly because restricting credit is even more costly. The last two years have shown that a few bank failures can pose real economic risk, and action is needed to stop the problem from spreading. The lesson for the next crisis is clear. Don’t think of fixing banks and supporting businesses as the same thing. Think of them as tools for different problems. When banks are sound but don’t have enough cash, quickly fixing them restores the flow of money. When businesses are the problem, design targeted, temporary help focused on productivity. If we’re disciplined – guided by good information, strict rules, and shared responsibility – we can save jobs, schools, and local services at a lower cost. The choice isn’t between banks and people. It’s about whether we rebuild the bridge that carries them both.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision). 2023. “Report on the 2023 Banking Turmoil.”

Bank for International Settlements (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision). 2024. “The 2023 Banking Turmoil and Liquidity Risk: A Progress Report.”

Bank of England. 2024. Identifying (Un)Warranted Tightening in Credit Supply. Financial Stability Paper.

Berger, Allen N., and Raluca A. Roman. 2017. “Did Saving Wall Street Really Save Main Street? The Real Effects of TARP on Local Economic Conditions.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 52(5): 1827–1867.

European Central Bank. 2023. “Euro Area Bank Lending Survey—October 2023.”

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). 2023. “Final Rule on Special Assessment for March 2023 Bank Failures.” Press Release, Nov. 16, 2023.

FDIC Office of Inspector General. 2023a. “Material Loss Review of First Republic Bank.” Dec. 31, 2023.

FDIC Office of Inspector General. 2023b. “FDIC’s Supervision of Signature Bank.” Apr. 28, 2023.

Financial Stability Board. 2023. Promoting Global Financial Stability: 2023 Annual Report.

Haavio, Markus, Antti Ripatti, and Tuomas Takalo. 2025. “Bank recapitalisation versus firm support: A fiscal criterion for crisis policy.” VoxEU/CEPR, Dec. 18, 2025.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabián Valencia. 2020. “Systemic Banking Crises Database II.” IMF Economic Review 68(2).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2023a. SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2023b. Ministerial Key Issues Paper: Future-Proofing SME and Entrepreneurship Policies.

Single Resolution Board. 2024. “The 2023 Banking Turmoil: Reflections and Lessons for EU Resolution Authorities.” Staff Paper #4.

SUERF (The European Money and Finance Forum). 2024. “Bank Lending in an Unprecedented Monetary Tightening Cycle: Evidence from the Euro Area.” Policy Brief.

U.S. FDIC. 2025. “Interim Final Rule on Special Assessment Collection—Updated Estimates as of Sept. 30, 2025.”

Comment