The Real Deal with Innovation After a Company Buyout

Input

Modified

Acquisitions slow innovation as buyer governance overrides speed Bound, don’t ban: output floors, retention covenants, access terms Educators: design for portability and use escape clauses

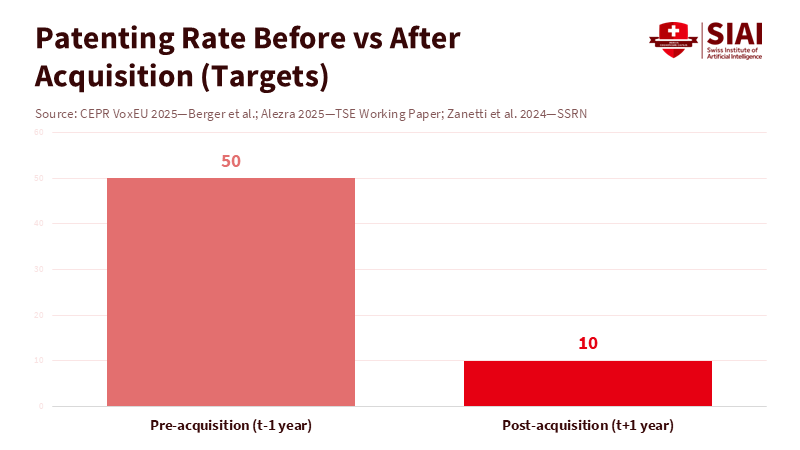

There's a number that should change how we think about innovation after a company gets bought. Before the deal, about half of all venture-backed startups filed for patents. After? Only about 10% do. This isn't just a small drop. It's what usually happens. It shows that innovation slows down after a buyout, not because the founders get lazy or the team loses people, but because the new owner has different priorities. These priorities – like staying compliant, avoiding brand risks, being efficient with money, and fitting everything together – make sense, but they also slow things down. When a big company's way of doing things meets a fragile startup, the startup usually bends. People often think we can come up with rules to keep the startup's pace within the new company. But the numbers tell a different story: innovation usually slows down after a buyout, even when it looks like a good match. So, the question isn't how to avoid the slowdown altogether, but how to limit it, plan for it, and work with it.

What the Numbers Say About Innovation After Buyouts

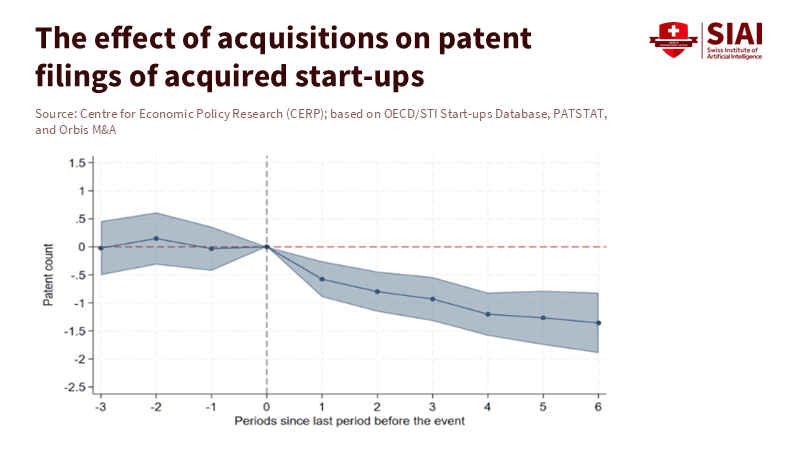

A study of 60 countries and 200 types of businesses found that start-ups don't come up with as many new ideas after they get bought out, compared to similar independent companies. The biggest clue is patents. Start-ups file way fewer of them after being acquired – about 1.5 times fewer than before the deal. Some stop filing them at all. Other studies see the same thing. One study reports that patent production drops by about 27% after an acquisition. Studies on inventors show that when a key scientist leaves after a merger, the number of patents they’re expected to produce in their career can fall by around a third. Basically, innovation slows down after a buyout because of structural and people changes. This isn't just in one industry; it happens in tech areas where you'd think companies would be good at absorbing new ideas. So, we should expect this to happen, not panic.

The effect gets worse when leaders leave. Founder-CEOs are super crucial in young companies, and when they leave, things get disorganized. Studies show that many founder-leaders leave within two years after a deal, often over 40% of them. Retention deals can help, but the overall pattern doesn't change. Even with good packages, they expire, and once the buyer is in charge, there is little room for radical risk-taking. There are successful scenarios where keeping the CEO for three years is linked to a smoother transition and product release. Things succeed only by integrating the start-up into the parent company, not by keeping it as it was. The main point for politicians is that innovation tends to slow after an acquisition, and leadership changes make it worse.

When Leaders Leave, Things Get Worse

A study of 60 countries and 200 types of businesses found that start-ups don't generate as many new ideas after they are bought out, compared to similar independent companies. The biggest clue is patents. Start-ups file way fewer of them after being acquired – about 1.5 times fewer than before the deal. Some stop filing them at all. Other studies see the same thing. One study reports that patent production drops by about 27% after an acquisition. Studies on inventors show that when a key scientist leaves after a merger, the number of patents they’re expected to produce in their career can fall by around a third. Basically, innovation slows down after a buyout because of structural and people changes. This isn't just in one industry; it happens in tech areas where you'd think companies would be good at absorbing new ideas. So, we should expect this to happen, not panic.

The effect gets worse when leaders leave. Founder-CEOs are super crucial in young companies, and when they leave, things get disorganized. Studies show that many founder-leaders leave within two years after a deal, often over 40% of them. Retention deals can help, but the overall pattern doesn't change. Even with good packages, they expire, and once the buyer is in charge, there is little room for radical risk-taking. There are successful scenarios where keeping the CEO for three years is linked to a smoother transition and product release. Things succeed only by integrating the start-up into the parent company, not by keeping it as it was. The main point for politicians is that innovation tends to slow after an acquisition, and leadership changes make it worse.

Why governance beats autonomy pledges in post-acquisition innovation

The usual promise in deals is independence within a platform. But that rarely lasts past the first budget. Once the parent company takes over, its approach to risk becomes the standard. Security checks delay releases. Brand rules limit design choices. Rules about data location and privacy change how products are built. Policies on buying and working with other companies prioritize compliance over speed. These are all smart for a company with millions of customers and regulators to answer to. But they're the opposite of what helped the startup grow in the first place. Even when independence is written into a contract, minor problems add up, like getting everyone on the same login system or integrating billing. Six small blocks can waste a quarter of a year. That wasted time means fewer experiments and safer plans, which weakens innovation after a buyout.

Money also plays a role. In competitive markets, retention bonuses are expensive and don't last long. Studies show that CEOs can get more than a year's salary in retention value, but senior engineers get less and have more restrictions. Meanwhile, other companies are trying to hire the most independent thinkers. When the acquired team loses one or two key founders, replacing them with internal managers rarely brings back the knowledge that kept the plan bold and consistent. Even when founders stay, the board's goals and expectations change. The buyer didn't buy a museum piece; they bought something they can use to add to their portfolio. So, instead of trying to keep independence, it's better to set limits that protect some meaningful bets while the parent company's ways of doing things take over.

A New Way to Think About Policy: From Blocking Deals to Setting Limits

Competition authorities are now stricter about deals that could hurt new competition. The U.S. Merger Guidelines now highlight risks to innovation and allow action even when there's little product overlap. The UK's new Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act adds new rules aimed at killer acquisitions. The European Commission has made it easier to approve low-risk mergers, but is still looking at the effects on innovation. Recent comments show that Brussels rarely blocks deals completely – only nine out of 2,833 reviews from 2015 to 2024.

These changes recognize that harm isn't always about prices; sometimes it's about the products that never get made. But the record also shows that blocking deals is rare, and for good reason: many acquisitions do spread knowledge and reach. So, a realistic policy should focus on setting measurable limits rather than just hoping for independence.

First, require companies to commit to innovation goals when they meet specific criteria, like having unique IP or clear milestones. These commitments can set minimum output goals, such as a certain number of field trials or R&D collaborations, over a period, with public reporting and penalties for missed commitments. Second, favor solutions that preserve competition rather than just promises about independent plans. If key parts are general-purpose, require access terms that last beyond the integration phase. Third, make some approvals depend on keeping the founding team or a core group for a period that matches product cycles, and tie-breaking the agreement to automatic IP escrow or spin-out rights. These aren't attempts to freeze the old company inside the new one; they're ways to limit the slowdown in innovation and keep future competition alive.

What Schools and Administrators Can Do

Schools, universities, and public systems buy from companies that are always being bought and sold. A plan that depends on a startup's roadmap can fall apart when the company is sold, and innovation slows down. There are ways to protect yourself. Build curricula and IT systems around open standards and data portability so that switching costs don't trap you when features disappear after a deal. Run pilot programs with milestones that transfer easily: if a delay pushes a promised feature beyond a semester, the contract should let you change the scope or move the budget. Avoid relying on proprietary connectors that a larger platform will want to rewrite. The thing to watch isn't the press release; it's how often they're shipping improvements six, twelve, and eighteen months after the deal.

Workforce programs should prepare students for the reality of working within platforms. The most critical skill isn't just inventing; it's navigating. Teams need to learn how to get through security reviews, legal blocks, and release processes without losing sight of the goal. Educators can simulate these problems in project-based courses: staged approvals, limited budgets, and integration gates. That teaches how to keep moving forward when you don't have complete independence. Administrators can push vendors to share product roadmaps with dates and to accept escape clauses if those dates slip. These steps don't fight the slowdown in innovation; they work around it.

What About the Arguments Against This?

One argument is that acquisitions help companies scale, and scale helps innovation. That's true for the buyer's portfolio, but the target's own output still tends to drop. In the CEPR dataset, both buyers and targets were innovative before the deal, but targets slowed the most afterward. The reason is that the parent company chooses which projects to fund, standardizes risk, and moves talent around. Evidence on inventors leaving shows that even small team losses can hurt idea pipelines. Policy shouldn't deny the benefits of scale; it should keep the path for future competition visible even as capabilities concentrate.

Another argument is that promises of independence work when enforced. Sometimes they do; longer CEO retention has been associated with smoother integration, and cross-border deals can have less turnover than domestic ones. But these are exceptions that prove the rule. The best outcomes align the startup with the platform and retime bets to enterprise cadences; they don't preserve the old tempo. Also, the market makes discipline more important: 2025 has been a busy year for large deals, especially in data-center and AI infrastructure. When things are being consolidated, there's less room for independent risks. That's when limits – not hopes – are most important.

We should stop believing that a small lab can keep running at startup speed inside a big platform just because the term sheet promises independence. The usual pattern is clear now: only about 10% of acquired startups continue to patent after the deal, down from about half before. That's the signal. Innovation slows down because control, not culture, is what really matters. The right response isn't to block most deals or to write empty promises of independence. It's to set clear limits on what must still happen after the deal: minimum outputs for a period, retention agreements tied to product cycles, access terms that keep future competition alive if promises slip. Educators and administrators can do the same: design for portability, demand dated roadmaps, and include escape clauses. If we accept that innovation has limits, we can stop asking it to be something it can't be – and make sure it still does what society needs.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Alezra, L. (2025). Being acquired and innovation: An empirical study. Toulouse School of Economics Working Paper.

Berger, M., Calligaris, S., Greppi, A., & Kirpichev, D. (2025). Stifling or scaling: Acquisitions and their effect on start-up innovation. VoxEU/CEPR Column.

Ederer, F., Seibel, R., & Simcoe, T. (2025). Digital (Killer) Acquisitions? Working paper.

European Commission. (2023). Notice on Simplified Procedure for Treatment of Certain Concentrations; Merger control notices and guidelines.

Federal Trade Commission & U.S. Department of Justice. (2023). Merger Guidelines.

Reed Smith LLP. (2025). Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 in force now (UK overview).

S&P Global Market Intelligence. (2025). Global M&A by the Numbers: Q3 2025.

Sayed, S. (2024). The impact of managerial autonomy and founding-team dynamics on entrepreneurial innovation. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP. (2024). UK revamps merger control, expanding CMA’s jurisdiction and thresholds for killer acquisitions.

WTW (Willis Towers Watson). (2024). M&A Retention Study.

Zanetti, M., et al. (2024). Acquisitions, inventors’ turnover, and innovation. SSRN Working Paper.

Comment