When Small Errors Become Big: The Nonlinear Phillips Curve and the Inflation Lesson Schools Can’t Ignore

Input

Modified

2022 proved the nonlinear Phillips curve under tight labor Use two-speed budgets: inflation >4% and v/u >1 trigger Teach regime-switching to keep small misses small

After the pandemic, inflation surged: in Europe, prices rose 10.6% in 2022, and in the US, 9.1%. These numbers are far above the 2% target. When inflation is this high, standard economic rules break down. The main argument is that school budgets, wages, and economics teaching only make sense if we adapt to a shifting reality: when the job market is tight, even small shocks have outsized impacts. If we stick to old models, we keep missing what matters when the economy is abnormal. We must recognize that rules shift in turbulent times.

The main thing is not to guess when inflation will stop rising. It's important to notice when things are different and use the right tools. Usually, a slight change in inflation doesn't matter much for school budgets. But in 2021 and 2022, even small mistakes cost a lot of money. That's what happens when things change: small expectation errors become big budget errors. School leaders need plans that start working when inflation and the job market tighten. And we should teach students that things aren't always predictable and straightforward.

Why does this matter for schools and budgets?

Under a nonlinear Phillips curve, price pressure increases when labor markets are tight. A tight market has many job openings for each unemployed worker, fast hiring, and rapid wage growth. These conditions were present from 2021 to 2022. Job openings in the US exceeded 12 million in March 2022, and the ratio of openings to unemployment rose above one, showing many jobs for each job seeker. In that situation, the curve becomes steeper. A slight increase in demand or costs can raise inflation quickly. For finance officers at universities, this means the indexation rules that worked at 2% no longer hold at 8 to 10%. The solution is to add “regime triggers” to wage steps, scholarship budgets, and procurement. When inflation goes beyond a certain point and stays there for a few months, the policy changes from slow, gradual adjustments to quicker, protective actions.

The classroom message is just as important. Many curricula still present the Phillips curve as if it were always linear, or they treat nonlinearity as a minor detail. Students need a more precise understanding: linear methods work well in a limited range but fail at the extremes. We should use the recent episode as a key case study. This case allows us to demonstrate how the slope changes when the vacancy-unemployment ratio goes over one, how expectations can remain stable or become unstable, and why local approximations can be misleading when the economy deviates significantly from its target. Economics students pursuing careers in school administration, EdTech, or policy will carry this way of thinking into their budget decisions. This approach can help reduce the risk of “small miss, big mess” planning in the next economic surge.

What the facts show from 2021 to 2025

The facts tell us two things. First, inflation rose way above 2%. Europe reached 10.6% in 2022, and the US hit 9.1% the same year. This happened while unemployment was low. The job market was tight, with many job openings. This is when things go wrong: minor problems turn into big price increases. Since then, things have cooled down. The IMF expects global inflation to continue falling, with rich countries returning to normal sooner than others. But the big price increase occurred when the job market was tight.

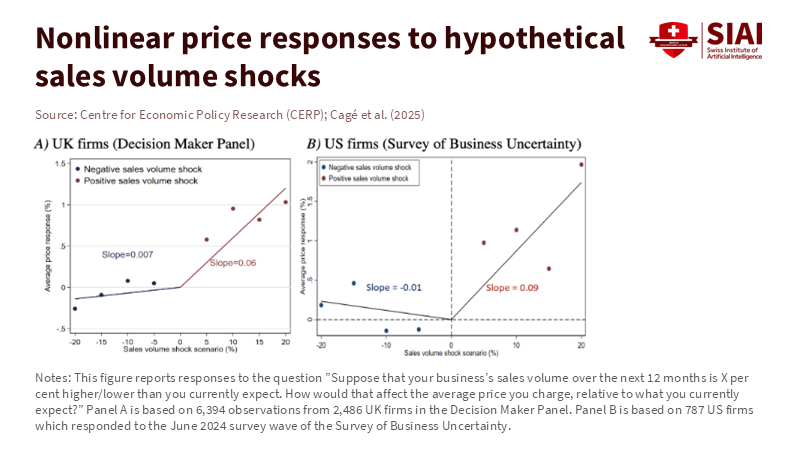

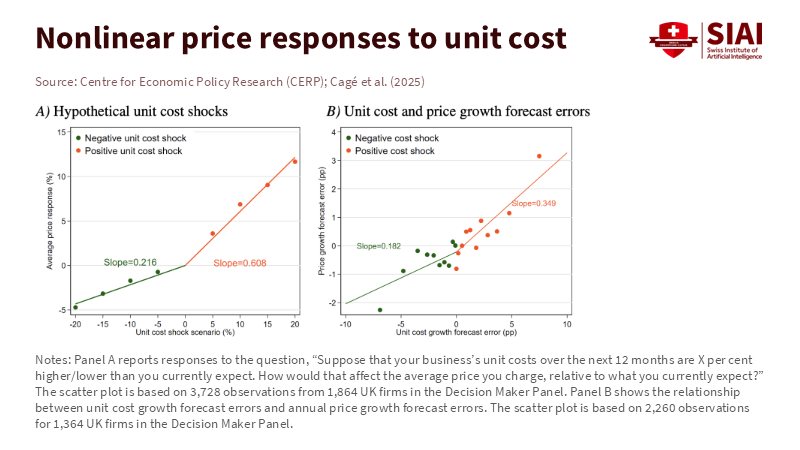

Second, experts disagree on the significance of the changes and on why. Some research shows that companies raise prices more easily than they lower them. This explains some of the extra price growth in 2022. Other studies say that changing things isn't that important. When you consider inflation expectations, things seem normal again. Both sides could be right. When inflation is high and the job market is tight, it seems prices will keep rising. At the same time, expectations can make things better or worse. For school leaders, the important thing is to act as if both of these things matter.

When small errors become big

If you think things are simple, you make small changes: raise tuition a bit, cut some spending, change a few contracts. This works when inflation stays around 2%. But when it doesn't, it fails. The changing Phillips curve means that things get worse when the job market is tight. A little extra wage pressure or cost can quickly mess up budgets. The answer is to have plans that work at two speeds. When things are calm, we use regular increases and long-term contracts. When things are stressed, we add temporary protections, check energy and food contracts more often, and have plans to help students and staff with living costs. The point is not to guess if things will change, but to watch for signs that they will and change plans when they do.

This also changes how we teach about expectations. When things are calm, mistakes don't matter much. When things are stressed, they get worse. Leaders should assume that people expect prices to stay the same. They should update their plans and protections more often when inflation reaches a certain level. This doesn't make the problem worse. It reduces the harm by quickly changing what people expect. This makes things fairer in the months that matter most.

Rules of thumb for school leaders

First, set clear triggers. Choose a few things to watch and write down what will happen if they change. Use inflation and a job-market measure, such as the number of job openings. When inflation is above 4% for a few months, and the job-opening number is high, you are in a dangerous zone. At that point, salary discussions should occur more frequently and include a mid-year review. Big contracts should be split into smaller parts, with the option to change prices for energy and food. Aid offices should increase student grants using recent inflation figures. Finance teams should protect against energy costs for the next two winters. The point is not to be perfect, but to avoid long contracts that assume things will stay the same when they won't.

Second, teach about changing conditions. Include the 2021–2023 situation in classes about economics, public finance, and education policy. Show students that things change when job markets are tight and that expectations matter. Use real numbers from those years. Ask them to write a budget plan for a university that must set tuition and wages in two situations. In one, inflation is at 2% and things are calm. In the other, inflation is at 8% and things are tight. Their plans should change in how they work, not just in how big they are. This helps future analysts see why the same small problem sometimes requires little action but can cause a big change at other times. It also prepares them to pay close attention to the job market as much as they do to inflation.

Third, manage expectations without overpromising. Leaders should clearly explain what will change if things move. If inflation is above 4% in July, we will increase cost-of-living grants. If job openings fall and unemployment rises, we will go back to normal. This helps staff and students plan, which stabilizes inflation expectations. It's easier to do when things are getting better, as many forecasts suggest. But it's good to start now, while people still remember the last surge.

Inflation jumped to 9%–11% in 2022. Simple thinking couldn't keep up. The changing Phillips curve is the right way to understand those months. It says that when job markets are tight, minor problems can quickly lead to big price increases. Some experts think the curve isn't that important once expectations are controlled. Others find that companies raise prices more easily than they lower them, which helps explain the problem. Both of these ideas matter. The practical step is to stop thinking that things are always simple and start treating simplicity as just a convenience. Education systems should have plans that work at two speeds, with triggers that change policies when conditions get hot. Economics classes should focus on current events to teach students how to spot when things change and act on them. If we do that, the next problem will still hurt, but it won't catch us off guard. Minor errors will stay small.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Anayi, L., Barnes, E., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Mizen, P., Thwaites, G., & Yotzov, I. (2025, December 23). A nonlinear Phillips curve helps explain the inflation overshoot. VoxEU.

Beaudry, P., Hou, C., & Portier, F. (2025, February). On the Fragility of the Nonlinear Phillips Curve View of Recent Inflation (NBER Working Paper No. 33522). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, July 13). Consumer Price Index News Release: June 2022. U.S. Department of Labor.

Congressional Research Service. (2024, February 28). Measuring Job Openings in the U.S. Labor Market (IF11054).

European Central Bank. (2024, March 11). The 2021–2022 inflation surges and monetary policy in the euro area (ECB Blog).

Eurostat. (2022, November 17). Annual inflation up to 10.6% in the euro area.

International Monetary Fund. (2024, April). World Economic Outlook: Steady but Slow.

OECD. (2024, December 11). Unemployment rates—Updated December 2024. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Number of unemployed persons per job opening (JOLTS).

Comment