When Everyone Moves at Once: Endogenous Risk in Banking After SVB

Input

Modified

SVB proved digital runs can topple banks fast Real-time diversification is the best defense Faster, targeted supervision blunts coordinated risk

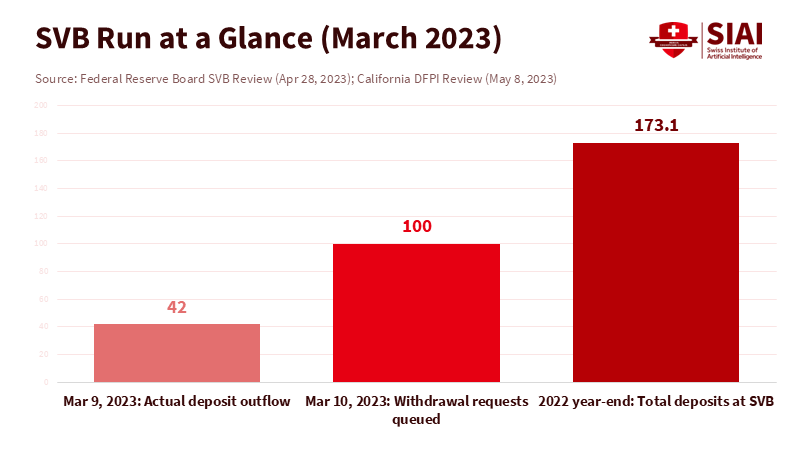

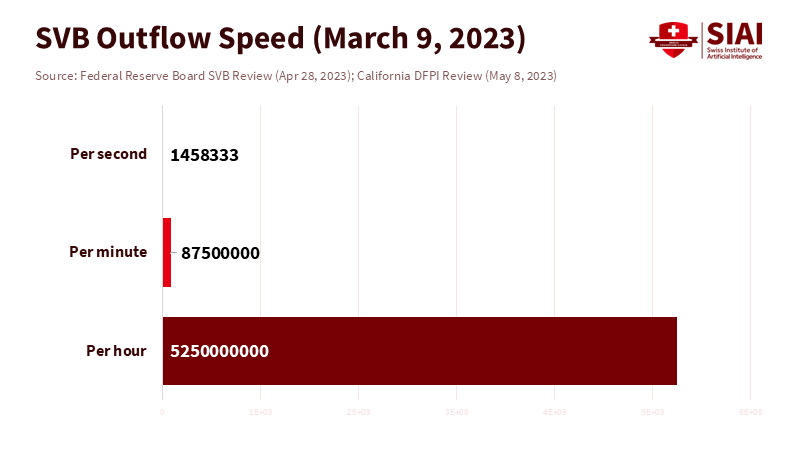

In March 2023, the future of financial oversight looked grim. Silicon Valley Bank lost $42 billion in deposits within hours, with another $100 billion set to go the next day. Almost all its deposits weren’t insured at the end of 2022. Smartphones, fast payments, and group chats turned rumors into a full-blown bank run—a risk from inside the system that grows when everyone acts together. The lesson isn’t about perfect prediction. It’s realizing that fast, collective action can crash institutions much more quickly than traditional oversight can react—a big problem in the age of social media. If we ignore this, future crises will strike just as quickly.

Why Internal Banking Risk Is About Coordination, Not Some Deep Mystery

Most people think crises are random hits to an otherwise stable system. But today's financial systems magnify small problems. Risk worsens as people copy one another. When interest rates rose in 2022 and 2023, many banks lost money on long-term investments. What was new was how quickly depositors shared information, moved cash, and panicked—algorithms and company chats amplified this, making large groups act together. Slow, report-based supervision can't keep up with such rapid change. Internal bank risk rises when information is unclear, balance sheets are hidden, and networks encourage similar behavior.

That’s why perfect supervision isn’t the answer. More data and models don’t guarantee stability if people’s reactions cause collapse. Supervisors can spot gaps in rates and liquidity or notice excess uninsured deposits. But if banks and their customers all react to the same triggers, efforts to control risk may drive more risky group behavior. Liquidity troubles aren’t just about individual errors—they’re about collective response. So, policy should shift to account for coordinated action rather than just isolated decisions.

What SVB Shows About Everyone Pulling Out Their Money at Once

Silicon Valley Bank is a perfect example of how quickly things can fall apart. At the end of 2022, about 94% of the bank’s deposits were uninsured, making customers more likely to panic and withdraw funds quickly. So when the bank announced losses and a need to raise capital, many customers reacted at once, moving millions in minutes via their phones. By March 9, $42 billion had been withdrawn, and regulators estimated that requests for March 10 would have reached $100 billion. It wasn’t a slow drain; it was a mad dash.

Since then, studies have shown that social media accelerated and magnified the bank run after the announcement. Banks whose customers were very active online saw more money leave and faced tougher stock markets, even if their basic finances were fine. Reports from the state and federal levels add more detail: the bank grew rapidly with uninsured deposits, didn't adequately protect itself against interest-rate risk, and didn't act quickly enough on internal risk warnings. But the main thing is that depositors acted together. When a bank’s biggest customers are always talking to each other, one warning post can make everyone panic together. Internal risk in banking isn't just some theory; it's what turned a normal interest-rate problem into a deadly crisis.

The problem spread beyond SVB. Signature Bank failed two days later. First Republic was taken over a few weeks later, even with special support. At the same time, money market funds received a flood of new cash as businesses and individuals moved their money to what seemed like safer places. By the start of 2025, U.S. money market funds had around $7 trillion in assets. These money movements are the other side of the same story: when risk feels close, people move together toward safety. This can take money away from regional banks, increase financial stress, and make people even more likely to withdraw their money next time.

How to Actually Diversify in Real Time

Saying 'diversify' might sound obvious, but the SVB story shows that diversifying the right way is still the best way to manage internal risk in banking. The trick is to diversify for speed, not just for profit. For companies, this means spreading money across different banks and investments with varying terms for repaying the money. It means using programs that automatically spread cash across insured accounts so you don't have to. It also means keeping some money in government money market funds and short-term Treasury bills that you can get to quickly. It's not about making the most money when things are calm—it's about setting up ways to move your cash smoothly when everyone gets scared at the same time.

For banks, diversifying means looking at both their liabilities and assets. Liability diversification starts with recognizing that having many uninsured deposits is risky. The goal isn't to eliminate all uninsured money. It's to avoid having too much money from a single industry, network, or group of influencers acting together. On the asset side, managing interest-rate risk is key. If deposits can disappear in hours, then having long-term investments with big unrealized losses is a sour mix. Protecting against this risk cost money in 2021–2022, and some banks skipped it. That decision made a coordinated bank run more likely. The data after SVB shows that many institutions still weren't ready to access the Federal Reserve's discount window quickly. Even after a year of reminders, less than half of U.S. banks had all the paperwork and security in place by the end of 2023. Being prepared is part of diversifying. Lines of credit you can't use fast don't count.

There's also the customer side. Internal banking risk grows when customers get their information from the same sources. Banks should assume that bad information will spread during a bank run and plan to respond quickly with facts, targeting their largest depositors. This means having updated communication plans. It also means giving clear, consistent information about liquidity and protecting themselves against risk—so that when rumors start, the bank has trustworthy facts ready to go. This won't stop all panic. But it will lower the chances that panic turns into everyone pulling out their money at once.

Supervision After SVB: Be Fast, Strong, and Nimble

Supervision needs to speed up. Reviews from the Federal Reserve, the California regulator, and international groups all say the same thing: supervisors saw many of the problems at SVB but acted too slowly and too gently. In fast-moving situations where everyone is acting together, delay is a risk. Examiners need to be able to step in sooner, especially at banks that are growing quickly with uninsured deposits. This could mean stricter liquidity rules, tighter limits on interest-rate risk, and clear consequences for failing to protect against risk. Too slow to act is a common judgment; policy should set early, public disclosure as the standard when a bank's structure makes bank runs likely.

Changing deposit insurance can also target the system's weak spots without large bailouts. One good option is covering business accounts used for payroll and payments. The goal is narrow: to make core operating cash less at risk, thereby reducing the likelihood of a coordinated bank run. It's not a blanket guarantee for all large balances. It's a careful move that reduces the risk of everyone withdrawing their money at once while still holding banks accountable for how they invest funds. Policymakers considered changes like this in 2023, and the case for it is stronger now that we understand how digital coordination works.

Finally, supervisors should make their own systems more nimble. Access to the discount window needs to be working, with security already set up and the stigma reduced. The data shows that many banks still hadn't set up or tested access by late 2023. This can be fixed. Supervisors can require regular tests, such as cyberattack tests, and share readiness stats to push those who are behind. They should also watch social media for early warnings, not to stop speech, but to understand how stories spread through depositor networks. Internal risk in banking is about how people act. If we only look at balance sheets and not the networks that make everyone act together, we'll be surprised again by how fast things can fall apart.

Prepare for the Next Time Everyone Acts Together

SVB wasn't the first bank to mess up interest-rate risk. But it was the first modern case of a large customer base using digital tools to act together in hours. That’s the main message for policy. Internal risk in banking will continue to cause sudden crashes when many people share the same information and can move quickly with little effort. The answer isn't trying to predict the future perfectly. It's shifting practically toward speed, diversification that works under pressure, and supervision that expects coordination.

We should focus reforms on where bank runs start: too much money from a single source, uninsured accounts, and a lack of clear communication. We should also finish the less exciting work: make sure access to the discount window is ready, security is in place, and tests make emergency money real at 3 a.m. Covering business payment accounts can take away the reason to run without giving a blank check. Clearer, simpler information can reduce the room for rumors. If we prepare for the next time everyone acts together, we won't need to perform miracles later. Internal risk in banking isn't going anywhere. The goal is to stop it from turning a thousand small moves into one destructive stampede.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements and Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Report on the 2023 Banking Turmoil. 2023.

Barr, Michael S. “Supervision with Speed, Force, and Agility.” Bank for International Settlements (speech). 16 February 2024.

California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation. Review of DFPI’s Oversight and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank. 8 May 2023.

Cookson, J. A., Fox, C., Gil-Bazo, J., Imbet, J. F., and Schiller, C. “Social Media as a Bank Run Catalyst.” 2023.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Options for Deposit Insurance Reform—Section 2. 2023.

Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank. 28 April 2023.

Federal Reserve Office of Inspector General. Material Loss Review of Silicon Valley Bank. 25 September 2023.

Investment Company Institute. “Money Market Fund Assets Hit Record-Setting $7 Trillion Mark.” 6 March 2025.

JPMorgan Asset Management. “What Happened to Silicon Valley Bank?” 10 March 2023.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. Recent Bank Failures and the Federal Regulatory Response. 28 April 2023.

Williams, Pete Schroeder et al. “Less than Half of U.S. Banks Ready to Borrow from Fed in Emergency.” Reuters. 12 April 2024.

Danielsson, Jon. “The Paradox of Perfect Supervision.” VoxEU. 30 May 2024.

Comment