Protective Trade Policy After Peak Globalization: From Infant Industries to Durable Technological Hegemony

Input

Modified

Tariffs buy learning time but, in tight supply chains, hit households first Protection works only when narrow, temporary, and performance-tied with investment Technological hegemony comes from factories and exports; tariffs are a short clock

In the first half of last year, parts and subassemblies accounted for almost half of global trade. That's a big deal if you're thinking about slapping tariffs on things. When nearly half of what's crossing borders is used to make something else, tariffs mess with everyone's supply chains. Take the U.S. upping tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles to 100% this year. The idea is to give American companies a leg up in batteries, chips, and cars. But history shows that tariffs usually hit consumers and businesses first, before any benefits appear. If the goal is to be a tech leader, we shouldn't just ask whether to protect industries, but how to do so carefully, for how long, and with the right investments, so that higher prices now become better productivity later, rather than just being a permanent tax.

When Tariffs Work (and When Supply Chains Push Back)

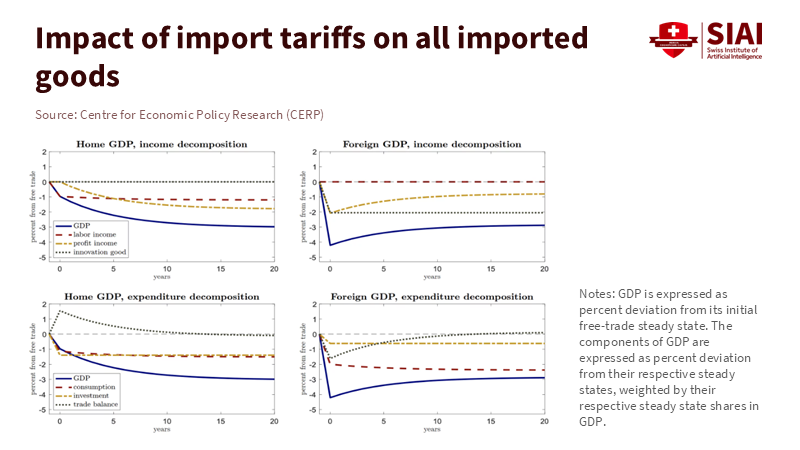

The argument for tariffs has always been about timing and picking the correct targets. Tariffs can give industries some room to grow, learn, and cluster together. They can also fix things when foreign countries are unfairly subsidizing their industries. But since 2018, it’s been pretty clear that U.S. import prices have risen almost directly with tariff rates, meaning importers (and regular folks) have paid the price. In 2018 alone, some studies said that tariffs cost the U.S. about $1.4 billion each month. The U.S. International Trade Commission later found that a 1% tariff increase raised prices by about 1% between 2018 and 2021. These aren't just guesses. There are real price increases on goods. If tariffs are too broad, they're basically a tax that shows up before any new factories are even built.

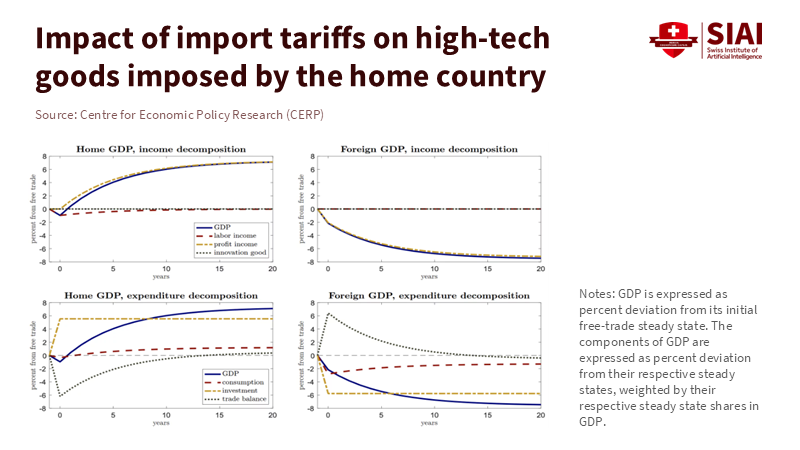

Timing is super important because everything is so interconnected. The WTO says that about half of global trade is in these intermediate goods. It dipped a bit to 48.5% last year as companies found new ways to buy stuff and shorten their supply chains. This means that a tariff on a final product can also raise prices on the parts that go into it, because those parts cross borders many times before they're assembled. Plus, if other countries retaliate or find different suppliers, it can ruin the whole plan. Think about electric vehicles and batteries: raising tariffs might make foreign EVs more expensive, but it can also increase the cost of the materials and equipment that American companies need. If we want to be a tech leader, policymakers need to realize that taxing rivals can also tax your own stuff, unless you have targeted help, duty refunds, or quickly build up enough domestic production.

What We Can Learn from East Asia: Risks of Isolating Yourself

People often point to East Asia to say that tariffs work. The story goes that governments protected new companies, they learned quickly, exports took off, and everyone ended up with better, cheaper stuff. The real story is more complicated. Japan protected its car industry for years with quotas and tariffs. Korea used import controls, credit, and tax breaks to boost its heavy industries. But they were successful when they protected industries only briefly, demanded results, and forced them to compete globally. Studies of Japan in the 1960s show that industries became more productive when they had to compete, not when they were shielded from others. Korea's success depended on pushing exports and upgrading technology, not just keeping everyone else out. The lesson isn't that tariffs build champions, but that tariffs can buy time while export pressure builds companies.

There's another lesson too. Even the best companies rely on global supply chains. About 37% of Korea's exports in 2022 came from other countries, as it depends on imported goods to make high-tech products. That's just how things are, and it's not necessarily a bad thing. But it does make broad tariffs risky: the more complex your products are, the more you rely on cross-border inputs, and tariffs raise the prices of those. History also shows that if you protect industries for too long without demanding results, they can fail. In the 1980s, Brazil tried to preserve its local PC makers, but people ended up paying more for worse computers, and the companies couldn't compete globally. So, protection can work, but only if it's focused, temporary, and pushes companies to export and learn, instead of just getting comfortable behind a wall.

Tariffs, Subsidies, and Your Wallet

The best way to become a tech leader is to combine tariffs with significant investment. The U.S. has been doing this. The CHIPS Act has awarded over $33 billion in incentives so far, with more loans on the way, to help companies expand in memory, logic, and packaging. Clean energy policies are also changing the game. By the middle of 2025, investment in clean energy and industrial decarbonization in the U.S. was close to record highs. Last year, there was about $60 billion in new manufacturing investment, and solar module capacity almost tripled to about 42 GW. With all of this going on, tariffs can stop predatory pricing long enough for subsidized factories to get up and running. But the costs are still real. Studies of the 2018–2019 tariffs found that they led to higher import and retail prices, costing households hundreds of dollars each year, even before later increases.

The details matter a lot in determining whether tariffs help or hurt you. Targeted tariffs on a few things can be combined with duty-drawback programs that protect exporters' costs. Government contracts and standards can boost demand for American-made stuff without taxing every shopper. Investment incentives can be tied to actual production, worker training, and technology improvements, so the benefits appear sooner than the costs. And being open about things is important. If you publish a schedule for when tariff rates will end, and set clear goals for companies getting subsidies, people will be more confident that tariffs are just a temporary way to boost productivity, not a permanent tax or a political game. Basically, tariffs should be a temporary tool, not a long-term solution. The real work comes from investing, learning, and scaling up.

A Smarter Strategy

So, what should we do? First, be precise. Use tariffs when there's clear proof of unfair practices (such as continuous subsidized overproduction, selling below cost, or geopolitical pressure) and when we can realistically build up domestic production within a set time frame. Second, tie protection to performance. Lower tariffs for companies that hit measurable goals: installed capacity, low defect rates, high yield, and export wins. Third, fix the input problem. If imported parts are subject to tariffs, offer automatic duty refunds for exporters and temporary rebates for producers who meet cost and quality targets. Fourth, don't just focus on tariffs. Standards agreements, reciprocal market-access deals for parts and equipment, and fast approvals for strategic plants can reduce the need for high tariffs.

Finally, invest in the basic stuff needed to scale up. Exporting and spreading knowledge were key to East Asia's success. Today, that means funding programs to help small- and medium-sized suppliers, aligning training with industry needs, and mapping supply chain bottlenecks. We also need to avoid the urge to declare victory too soon. Being a tech leader is about gradual improvement: achieving higher yields, upgrading suppliers, and fixing logistics problems until you have globally competitive costs. Tariffs buy you time; well-run factories make you competitive for good. Think of tariffs as a timer and factories as the strategy.

Protect to Learn, Not to Hide

We started by noting that almost half of global trade consists of intermediate goods. That's the world we're dealing with. In this world, tariffs act like taxes that spread through supply chains. They can be justified when they counter unfair subsidies or buy time for domestic companies to learn, but they can't be your only move, and they can't last forever. The way to become a tech leader isn't by building a wall; it's by creating a ramp. Build it with disciplined, temporary protection; subsidies tied to performance; standards and contracts that reward lower costs and better quality; and continuous investment in people, processes, and facilities. Use the tariff timer wisely. If, by the time it runs out, our producers can match global prices and export on a big scale, folks will stop paying for protection and start benefiting from better productivity. That's the only deal that's worth making.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare. American Economic Review: Insights.

Cavallo, A., Gopinath, G., Neiman, B., & Tang, J. (2021). Tariff Pass-Through at the Border and at the Store. American Economic Review: Insights.

Clean Investment Monitor. (2025). Clean Investment Monitor: Q2 2025 Update. Rhodium Group & MIT CEEPR.

International Energy Agency. (2025). World Energy Investment 2025: United States Snapshot. IEA.

Irwin, D. A. (2021). Policy Decisions that Transformed South Korea. NBER Working Paper.

Kiyota, K., & Okazaki, T. (2015/2016). Assessing the Effects of Japanese Industrial Policy Change during the 1960s. University of Tokyo / RIETI Discussion Paper.

National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2025). U.S. Department of Commerce Announces CHIPS Incentives Awards. NIST News Release.

OECD. (2024). The Return of Industrial Policies. OECD Publishing.

UK Department for Business and Trade. (2025). South Korea: Trade and Investment Factsheet (TiVA-based indicators).

United States International Trade Commission. (2023). Certain Effects of Section 232 and 301 Tariffs Reduced Imports and Raised Prices (USITC Press Release).

United States Trade Representative. (2024). Section 301 Modifications Determination: Tariff Changes (including EVs and Batteries).

World Bank. (1993). The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. World Bank.

World Trade Organization. (2023). WTO Forecast Note: Intermediate Goods Share Fell to 48.5% in H1 2023.

World Trade Organization. (2024). World Trade Statistics 2024. WTO.

Comment