Fact-Checking Without Censorship: How to Rebuild Trust on Social Platforms

Input

Modified

Label fast and show sources Track latency and publish audits Teach verification; support independent checks

Right now, about half of all adults get their news from social media. So, making sure the info they see is accurate (but without blocking stuff) isn't just a minor issue—it's how news works today. In the US, over half of adults sometimes get news from social platforms. Videos are watched mostly on these platforms, not on news websites. Also, more people are avoiding the news altogether. Because of this—lots of platform use + people tuning out—we need ways to correct wrong info without being too pushy. We don't want to control what people say, but we need to make sure accuracy matters when people decide what to believe. What we've seen shows this can actually work. When platforms tag or give context to false posts, fewer people engage with them. But if they're slow, the fake stuff spreads fast. So, the question isn't whether to do anything. It's about making sure that checking facts (without blocking stuff) is just how the internet works.

Why fact-checking without blocking is important

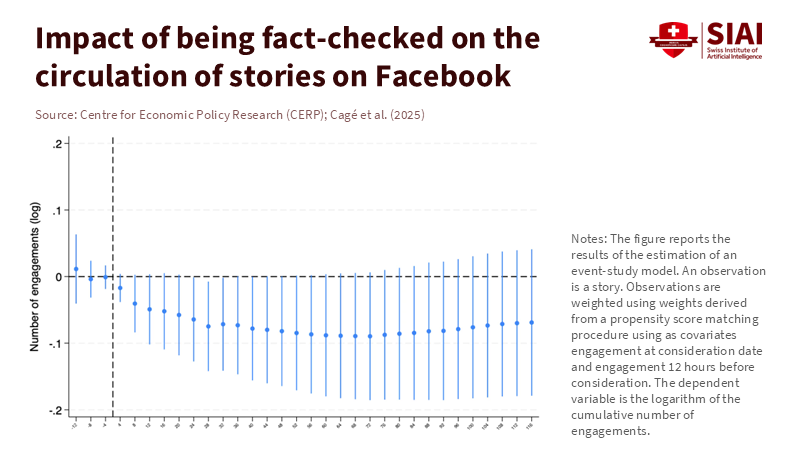

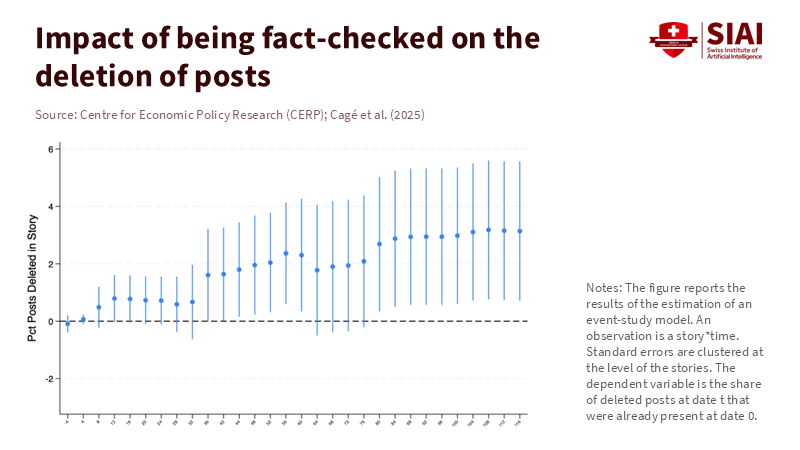

The things we've studied clearly show that it works, even if people argue about it. Research from Facebook shows that labeling a story as fake reduces engagement by about 8% on average, and even more when done quickly. This mainly changes how people act: they delete posts or share less when they know something is wrong. It also doesn't cost much to remove a fake post. This isn't about deleting everything. It's just a nudge to help people make better choices. A study on X shows that when a Community Note appears, fewer people repost, like, reply to, or view the post. So, we're stopping the spread without deleting anything. The key is to be fast, make the note clear, and be specific. An early note is way better than a hidden removal that happens late.

But people are worried, and that's fair. Platforms aren't neutral. They make money from ads and have systems that push what people are most likely to engage with. Sometimes this means that crazy or weird stuff gets more attention. Research shows that prioritizing engagement can get eyes on the post, but it can also tell people to see more divisive or misleading posts. In January, Meta/Facebook said that it would stop having third-party fact-checkers in the US. Instead, they'll use a Community Notes model, and they are also loosening rules. Some people didn't like this, while others thought it was a good change. Either way, this shows the problem: things that increase engagement can also mess with accuracy. If we want fact-checking without blocking, we have to fix how these systems work.

Another concern is that the people checking the facts might be biased, or that the platform's own money-making strategies can be biased. People make mistakes. Studies say that professional fact-checkers don't always agree, and there are lots of things that can screw up their decisions, like being under pressure, already having strong beliefs, or the category they put something in. So, it's easy to lose trust. If a label seems biased, or if you can't see how a decision was made, people will ignore it or fight back. That's why it's best to show why something is false, who checked it, and make appeals fast. We don't need to win some culture war. We just need to make it a little harder to share fake posts and less intelligent to ignore a warning.

Why platforms mess things up—and how to fix them

Platforms control what people see through their ranking systems, recommendations, and default settings. These systems respond to things like clicks and watch time, not whether something is actually true. Because of this, wrong info can do better. It's often new, gets people emotional, and is easy to read quickly. The fix is to make the systems care about accuracy, without stopping people from saying whatever they want (within the law). We can start by giving rewards to context that's fast and easy to understand. A warning that pops up in minutes makes a difference, but one that comes after something has already gone viral doesn't. For example, the Community Notes model gives mixed results. When the notes appear late, they don't do much. But when they're fast, and people see them, the spread goes down. So, community models can work; we just need to make sure they're quick and well-placed.

Rules can also help. They don't need to pick what's true, but they can force companies to open up their systems. The Digital Services Act (DSA) in the EU requires big platforms to give researchers access to their data and to explain why they made certain moderation decisions. This isn't blocking content; it's just being open. X has even gotten in trouble and been fined for not being transparent enough. This is where the government should focus by demanding data access, risk assessments, and appeal systems that work. These changes affect how companies act and let researchers see if fact-checking is really happening without blocking speech.

How to set up fact-checking without blocking

First, separate the decisions. Who decides if something is true should be separate from who decides what gets shown to users. Veracity should be based on clear rules, categories, and people. Then, the distribution should be affected by these signals. Early labels should make it harder to share something. Repeat offenders should be shown lower in feeds, based on the accuracy of their posts, not who they are or what they believe. This system works because when labels appear, people interact less with false posts, and accounts don't share wrong info as much later on. This stops people from doing bad things while still letting them speak.

Second, speed matters. Platforms already measure how fast everything else loads. They should measure how fast context is added to risky claims and then share the data. Community models can help here. Studies show that people trust crowd-generated context more (especially in heated situations) when the notes are good and follow the rules for different viewpoints. A good goal is to have 80% of high-velocity claims get a visible context note within 60 minutes. This isn't a rule about what can be said. It's just an operations rule. It respects freedom of speech, but it also understands that things can spread super fast online. A late label is useless.

Third, make it easy to challenge things. Every label should have a show-your-work button that explains the sources behind the decision, and a way to appeal for a human review quickly. People won't always agree, but explaining things and holding fast appeals stop everyone from crying that things are unfair. Again, the DSA offers a good model: rights to explanation, researcher access to data, and transparent databases. Platforms can use these practices globally. Fact-checking without blocking is a design choice that can work across different places if the process, not the viewpoint, is the most important thing.

Fourth, give users a choice. Let people pick from vetted fact-checking services or crowd-context feeds, just like they pick a spam filter. Some people might want only professional labels, while others prefer crowd notes. The platform should let them choose, but it needs to have common standards for what gets shared, plus precise performance data. This reduces the risk of things failing and creates competition over accuracy and speed, not over ideology. Research shows that professional labels are often seen as more in charge, and crowd labels can seem more fair and reduce post diffusion rates. Using a mix of models minimizes the risk of relying too heavily on a single approach.

Accountability that protects speech

Teachers and professors should show their students how to pause and read labels. They should teach them how to read a context note, review the sources, and decide whether to share something. Have students do verification drills, such as tracing a viral claim back to its source and writing a quick summary of what they found. And it is essential to do this on the platforms students actually use. A generation that treats context labels like nutrition facts will share better and faster. That's fact-checking without blocking. Admins should find tools that make transparency the norm. That has dashboards that show how fast labels appear, the results of appeals, and how many school devices saw flagged content during significant news events. Districts that are testing student platforms should include a show your work link for any moderation. These features calm things down when parents complain about bias. They also build records that matter when a platform update breaks the flow of accurate info. In a world where almost half of adults are tired of the news, lighter labels with faster context reduce problems without pushing people away.

Politicians should focus on checking, not on picking answers. They should fund independent studies on how quickly labels appear and how useful they are. They should also protect platforms that give high-quality data to researchers, as the DSA does. Tie government contracts and ads to transparency performance. If a platform wants government money, it should meet specific standards for data access and appeal speed. When platforms experiment with crowd notes, they should publish public plans for studying them and report the results quarterly. The evidence is building. First analyses showed that crowd notes had little impact, likely because they arrived late. Newer analyses show that they can significantly reduce the spread rate once a note is attached.

The most substantial criticism is that labels limit speech and lead to viewpoint control. The best way to respond is to keep everything visible while changing how it is seen. Label before you demote, demote before you remove, and remove only content that is clearly illegal or has signs of coordinated manipulation. Post your rules, tell people how often you make mistakes, and tell them how fast you respond. Combine professional checks with crowdsourced context to make things faster. And back it all up with audit records and researcher access. That model reduces the space where people can claim censorship, while still cutting the oxygen that lets false content spread. That's what fact-checking without blocking can do in practice.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press (2024). About 20% of Americans regularly get their news from influencers on social media, report says.

Cagé, J., Gallo, N., Henry, E., & Huang, Y. (2025). Fact-checking reduces the circulation of misinformation. VoxEU/CEPR.

Drolsbach, C. P., et al. (2024). Community notes increase trust in fact-checking on social media. PNAS Nexus.

European Commission (2024). How the Digital Services Act enhances transparency online.

European Commission (2025). FAQs: DSA data access for researchers (Article 40).

Jia, C., et al. (2024). Understanding how Americans perceive fact-checking labels. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review.

Milli, S., et al. (2025). Engagement, user satisfaction, and the amplification of biases in ranking. PNAS Nexus.

Pew Research Center (2024). How Americans get news on TikTok, X, Facebook and Instagram.

Pew Research Center (2025). Social media and news fact sheet.

Poynter Institute (2024). Let’s say it plainly: Fact-checking is not censorship.

Reuters Institute (2024). Digital News Report.

Reuters (2024). EU says X breached DSA online content rules.

Slaughter, I., Peytavin, A., Ugander, J., & Saveski, M. (2025). Community notes reduce engagement with and diffusion of false information online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Ventura, T. (2023). Reducing exposure to misinformation on WhatsApp in Brazil. VoxDev.

Zuckerberg, M. (2025). More speech and fewer mistakes. Meta company announcement.

Comment