Beyond Winners and Losers: Rethinking China’s Global Economic Influence

Input

Modified

China’s global economic influence creates shared dependence It reshapes rich-country industry and developing-country debt Open-source AI deepens this reliance, making resilience vital

In 2023, China accounted for about 29% of global manufactured goods. At the same time, it became the largest official creditor to developing economies, holding at least US$1.1 trillion of their debt. This dual role clearly highlights China’s global economic influence. Factories in North America and Europe rely on Chinese components to keep prices low and support clean-tech projects. Finance ministers from Accra to Islamabad count on Chinese loans, rollovers, and rescue packages to balance their budgets. The standard narrative suggests two responses to this rise: wealthy countries as anxious losers and poorer ones as grateful partners. However, the data tells a different story. China’s global economic clout has created a shared constraint. In this situation, both the 'winners' and 'losers' are bound by the same economic forces, which manifest in various ways, from closed factories to strained treasuries, and are now impacting open-source artificial intelligence. The distinction between “winners” and “losers” is less significant than the shared dependence that underlies it.

How China’s global economic influence reshaped factories and fiscal space

The standard view starts with trade. Wealthy nations are said to resent China’s influence because of cheap imports that have dismantled parts of their manufacturing bases. However, consumers have benefited from lower prices. There is some truth to this. Research on the “China shock,” a term used to describe the rapid increase in Chinese imports and its impact on global manufacturing, reveals that rising imports from China led to the loss of about one million manufacturing jobs in the U.S. and 2.4 million jobs overall between 1999 and 2011, with significant losses in particular regions. Meanwhile, China’s share of global manufacturing reached approximately 29% in 2023, outpacing the combined share of the next four manufacturing economies. Studies in Europe draw similar conclusions: while tariffs and anti-dumping measures have slowed Chinese competition in some areas, they haven’t changed the fact that producers in wealthy economies now face tough competition from a rival with vast scale, automation, and strong governmental support. In simple terms, Chinese subsidies and industrial policies reduced the time others had to adjust. Even firms that were innovative and efficient found it hard to compete against a wave of underpriced inputs and finished goods.

Despite losing factories, many of these countries still depend on China’s influence to meet new policy objectives. The International Energy Agency and other experts estimate that China now accounts for about one-third of global clean-energy investment. It is building nearly twice as much wind and solar capacity as the rest of the world combined. European and North American climate goals hinge on Chinese solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles that remain affordable due to the same subsidies that undermine local industries. A recent study for the Centre for Economic Policy Research labels China the world’s “sole manufacturing superpower,” noting that all major manufacturing nations source at least 2% of their industrial inputs from China. This means that the industrial shock and the climate transition are interconnected aspects of the same dependence. Wealthy countries did not simply “lose” while developing nations “won.” They received lower prices and faster decarbonization, but at the expense of becoming strategically reliant on Chinese production, a situation that will take decades to change.

In contrast, developing nations view the situation quite differently. China’s influence is often seen as a lifeline: a buyer of raw materials and a funder of infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative, a global development strategy adopted by the Chinese government involving infrastructure development and investments in nearly 70 countries and international organizations. AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance dataset documents over 20,000 projects worth around US$1.34 trillion across 165 low- and middle-income countries from 2000 to 2021. As Chinese demand rose, commodity prices increased; infrastructure expanded in regions where Western lenders hesitated to invest. However, the financial picture has grown more challenging. AidData’s recent “Belt and Road Reboot” report estimates that developing countries owe China at least US$1.1 trillion, possibly as high as US$1.5 trillion. About 80% of China’s overseas lending to the developing world now supports borrowers who are struggling financially. Additional research by Horn and his colleagues conservatively estimates that around 60% of this debt was in distress by 2022.

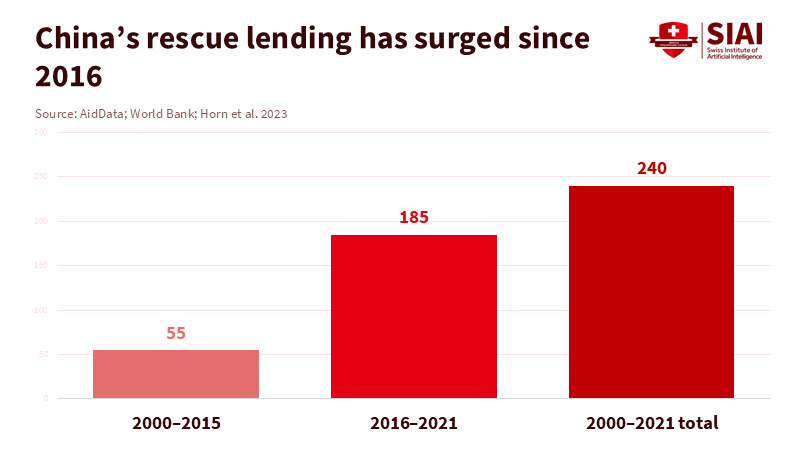

Rescue lending has become the fastest-growing aspect of this relationship. Since 2000, China has provided around US$240 billion in bailout loans, mostly between 2016 and 2021, to at least 22 countries facing difficulties in repaying previous debts. A 2025 report from the Lowy Institute warns that the poorest 75 countries will pay a record US$22 billion to Chinese creditors this year, which represents more than half their total external debt service. These repayments strain budgets for health, education, and climate resilience, giving Beijing power over the timing and nature of fiscal adjustments. The same natural resources that once fueled growth now serve as collateral in opaque contracts, which may involve escrow accounts or future revenue commitments. Rather than experiencing straightforward BRI “win-wins,” many countries find themselves in a cycle of commodity exports, hefty project loans, and high-interest rescue packages when cash flow issues arise. They sold oil, copper, or land, effectively mortgaging a portion of their policy autonomy.

Overall, these trends indicate that China’s global economic influence has not resulted in two distinct camps of resentful wealthy countries and grateful poorer ones. Instead, it has created a unified structure with varying symptoms. In advanced economies, this constraint reveals itself as diminished industrial diversity and challenges in rebuilding vital sectors without Chinese inputs. In developing nations, it manifests as crowded debt schedules and the pressure to negotiate significant decisions with a creditor that is also a major trade partner. Polling in Africa illustrates this complexity: Afrobarometer surveys show that large majorities view China’s economic and political influence positively, often more so than that of the United States or the European Union. However, leaders also recognize debt and reliance on a single partner as growing risks. The global landscape is not simply divided into winners and losers; it is entangled in a shared web of dependence on Chinese finance and supply chains.

China’s global economic influence moves from steel to code

The next phase of China’s global economic influence is unfolding in software rather than just steel. By 2025, Chinese open-source artificial intelligence models reached the top of numerous global leaderboards. TechWire Asia reports that models from DeepSeek and Alibaba now lead several benchmark rankings and compete with, or even surpass, well-known American systems. DeepSeek’s R-series models have triggered a global price shift: media reports detail development costs far lower than those of U.S. rivals, with per-query prices a fraction of those of leading American models. Reuters and other outlets have noted that Alibaba’s Qwen 2.5-Max reportedly outperforms both DeepSeek and top Western models. At the same time, Baidu plans to open-source its Ernie model to address competitive pressures. A senior partner at Andreessen Horowitz recently expressed the sentiment from Silicon Valley: open-source AI is “China’s game right now.”

Unlike the Belt and Road Initiative, this aspect of China’s global economic influence expands without large loans or physical projects. An infrastructure project requires contracts, feasibility studies, and, in some cases, parliamentary approval. An open-source model needs just a few commands and a basic server. Al Jazeera’s recent coverage reveals how swiftly U.S. startups and established tech firms have adopted Chinese AI systems, prioritizing performance, price, and fine-tuning flexibility over national origins. Once developers standardize around Chinese model families and toolchains, Beijing gains influence through default settings and technical standards rather than explicit conditions. This soft infrastructure may eventually prove more significant than the ports and power plants of the earlier Belt and Road projects. It integrates China’s influence directly into code, documentation, and daily workflows in labs and companies far from Beijing.

For the Global South, the overlap between China's physical and digital economic influence is already apparent. Many BRI projects have included data centers, fiber-optic networks, surveillance systems, and e-commerce platforms built by Chinese firms. As open-source Chinese models become standard within these systems, host governments may rely on Chinese vendors not only for hardware maintenance and debt restructuring but also for updates to core algorithms for policing, taxation, social protection, or education. This reliance presents clear downsides: risks of lock-in, exposure of sensitive data, and the chance that imported systems may reflect illiberal governance norms. Yet it also offers real advantages. Affordable AI reduces barriers for local developers, universities, and small businesses that cannot afford pricey proprietary models. In health, agriculture, and education, Chinese tools can help fill service gaps that Western donors and markets have overlooked. For both advanced and developing economies, the key question is no longer whether to respond positively or negatively to China. It is whether they can influence this new wave of China’s global economic influence, rather than merely accept it.

Governing in the shadow of China’s global economic influence

Policy has not kept pace with the scope of China’s global economic influence. In many wealthy countries, discussions still fluctuate between calls for decoupling and the belief that market forces alone can resolve distortions. Neither perspective is convincing. The scale of China’s manufacturing sector and its essential role in clean-energy supply chains make total decoupling unrealistic. At the same time, ample evidence of subsidies, overcapacity, and strategic export pushes justifies targeted defensive measures. The primary focus should be on rebuilding domestic industrial ecosystems while addressing specific choke points where reliance on a single Chinese supplier would be particularly harmful in a crisis. This necessitates ongoing investment in skills, R&D, and grid infrastructure rather than just border tariffs. It also requires greater transparency into how Chinese state support operates, so that voters understand why firms in their own countries struggle to compete, even when they perform well.

Developing nations face a more brutal balancing act. For many, China’s global economic influence has provided visible infrastructure and lower financing costs than what Western markets historically offered. Surveys like Afrobarometer show that citizens across much of Africa still regard China as a trustworthy partner, often more so than Western powers. Moving away from that partnership is neither feasible nor desirable. However, policymakers can work to establish a more sustainable relationship. They can demand public disclosure of loan terms, resist excessive collateralization of strategic assets, and collaborate more closely with multilateral institutions when restructuring debt is necessary. They can view Chinese digital platforms and AI models as just one option among many, rather than as the state’s default operating system. Diversifying suppliers across finance and technology can be costly in the short term. Still, it is the only way to prevent China’s influence from evolving into outright dependence.

A country that produces nearly a third of global manufacturing output and holds over a trillion dollars in developing-country debt will influence governments worldwide. As open-source AI spreads, that same country is poised to set many technical standards that will shape how information is processed, how students learn, and how companies compete. The notion of “two responses” no longer aligns with this reality. One dominant pattern emerges: a world adjusting, often uneasily, to China’s global economic influence in trade, finance, and software. The task ahead is to build sufficient resilience within that framework to enable independent choices. This requires educators who can explain interdependence without promoting nationalism, public officials who grasp both debt contracts and data flows, and policymakers who recognize China as neither a savior nor a villain but as a structural fact. The aim is not to escape China’s orbit but to ensure that orbit does not dictate the future.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AidData. (2023a). AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0.

AidData. (2023b). Belt and Road bailout lending reaches record levels, raising questions about the future of China’s flagship global infrastructure program.

AidData. (2023c). Belt and Road Reboot: Beijing’s Bid to De-Risk Its Global Infrastructure Initiative (Executive summary).

Al Jazeera. (2025a). China’s AI is quietly making significant inroads in Silicon Valley.

Al Jazeera. (2025b). Why China’s AI startup DeepSeek is sending shockwaves through global tech.

Autor, D. (2021). Q&A: David Autor on the long afterlife of the “China shock”. MIT News.

Baldwin, R. (2024). China is the world’s sole manufacturing superpower: A line sketch of the rise. VoxEU / CEPR.

ChinaPower Project, CSIS. (2024). Measuring China’s manufacturing might.

ChinaGlobalSouth & Afrobarometer. (2025). China tops favorability rankings in Africa, outpacing U.S. and EU.

Ember. (2025). China Energy Transition Review 2025.

France 24. (2023). China owed more than US$1 trillion in Belt and Road debt: report.

Guardian. (2023). China spent $240bn on Belt and Road bailouts from 2008 to 2021, study finds.

Guardian. (2024). China building twice as much wind and solar power as the rest of the world.

Guardian. (2025). Chinese startup DeepSeek disrupts the artificial intelligence sector.

International Energy Agency. (2024–2025). World Energy Investment reports and China country analysis.

Lowy Institute. (2025). Poorest 75 nations face “tidal wave” of debt repayments to China in 2025, study warns.

Statista. (2025). Top 10 countries by share of global manufacturing output in 2023.

TechWire Asia. (2025). China open-source AI models dominate global rankings.

Comment