Make Markets Do the Work: COP30 Trade Rules, Not More Pledges

Input

Modified

COP30 must set enforceable trade rules Join a carbon price-floor club with fair borders Recycle revenues and standardise carbon data to reward clean goods

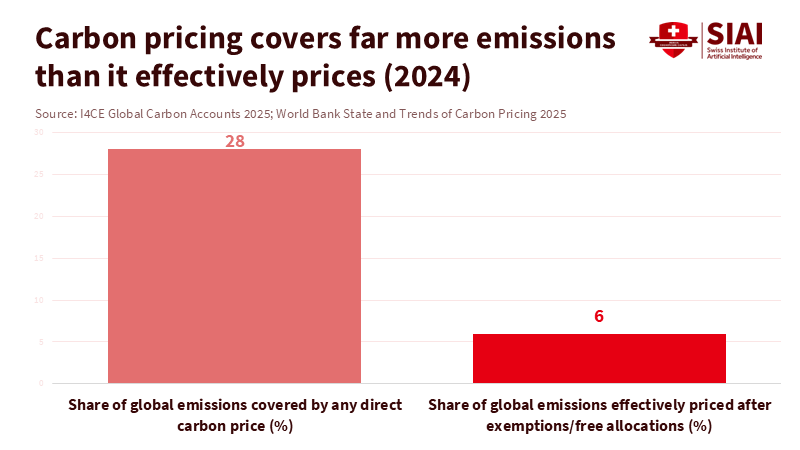

The most crucial climate figure this month is not another record of warming. It is 28%, the share of global greenhouse gas emissions now under a direct carbon price. This is a historic high. Yet the planet is still on track for something like 2.5 to 3.0°C this century based on current trends. The urgency of the situation cannot be overstated. The difference between market pricing and scientific demands is what COP30 hinges on. If we do not turn goals into enforceable COP30 trade rules—rules that change incentives at borders, in finance, and along supply chains—the world will continue to pay for carbon in press releases instead of in prices. The good news is that the building blocks are already in place: partial carbon markets, emerging border measures, and better accounting of emissions in traded goods. The job in Belém is to connect these elements so trade boosts decarbonization instead of hindering it.

From promises to ports: why COP30 trade rules are the missing lever

This summit arrives in a world weary of promises. The venue itself symbolizes this contradiction: Belém sits at the mouth of the Amazon, yet Brazil has moved ahead with new offshore exploration while scrambling to accommodate tens of thousands of delegates in a city lacking beds. The meeting began amid doubts about logistics, access, and ambition, with headlines questioning whether the process is “broken.” These doubts relate not only to appearances. They show a more profound concern that annual statements have pushed aside implementation. When the world’s most significant emission cuts now occur through supply chains—steel, cement, fertilizers, ships, and data centers—conferences that do not rewrite the trade rules cannot close the gap. The task this time is to shift from speeches to customs codes.

Deadlines have slipped, making it even more urgent to establish rules for trade flows. Fewer than one in 10 countries met the original deadline for submitting their next climate plans, prompting an informal extension to late September. By the end of that period, the UN had recorded only sixty-four new pledges, covering roughly a third of global emissions. This is hardly enough clarity to guide investment. Meanwhile, criticism of the talks has focused on the flood of lobbyists and the disparity in negotiating capabilities between rich and poor countries. These critiques matter, but a stronger point is practical: the most significant lever available is not another set of abstract targets; it is a concrete set of COP30 trade rules that favors decarbonized production in markets.

What enforceable COP30 trade rules can do

The fastest way to scale is a group of willing economies that accept differentiated carbon price floors—higher in wealthy countries and lower in middle-income ones—while tying membership to verifiable pricing or equivalent performance standards. The IMF’s floor numbers remain a practical reference: around $75 per ton for high-income countries, $50 for middle-income countries, and $25 for low-income countries. Countries could meet the floor through a tax, an emissions trading system, or a hybrid that produces an equivalent effective price. Importantly, border-adjusted tariffs would apply to non-members, with automatic discounts for clearly low-carbon producers. The prize is not theoretical. Revenues from carbon pricing exceed $100 billion a year, coverage has reached 28% of global emissions, and modeling shows price floors can achieve significant cuts while respecting different starting points. This club would secure progress by aligning markets rather than just ministries.

Border measures will still set the hard edge of the system; they must be lawful, simple, and fair. The European Union’s CBAM offers one model: a transitional reporting phase, a clear timetable, and a final regime linked to the domestic carbon price as free allowances phase out. COP30 should negotiate mutual-recognition protocols so that compliant exporters face a single audit, not many, and agree that a fixed percentage of CBAM-type revenues is recycled into transition finance for low-income suppliers that meet standards. This approach makes border fees feel less like protection barriers and more like an on-ramp. Pair this with uniform rules for counting emissions embedded in traded goods—the share of global emissions linked to trade is about one quarter—and you create a system that rewards genuine decarbonization across supply chains instead of merely moving pollution. That is what lasting COP30 trade rules should achieve: simplify complexity, increase credibility, and provide cash and certainty where they matter.

The U.S. problem—and the workaround

There is a political reality to address: the United States lacks a federal carbon tax or a national cap-and-trade system. Its primary tool is a subsidy-driven industrial policy, not explicit pricing. In a year when Washington has backed away from several international climate initiatives, no one should expect a sudden acceptance of a global carbon price. But stagnation is not necessary. A group that recognizes outcome-based compliance can include economies meeting intensity benchmarks without an explicit tax. U.S. companies that document cleaner steel or cement should receive border credit even if their government does not implement a price. This keeps American exporters involved and reduces pressure to disrupt the system. The alternative—expecting a country with no federal price to commit to a global one—turns the ideal into an obstacle.

This workaround is not a loophole. It is a bridge. The fact is, successful groups are those open to performance-equivalent paths and strict on verification. Performance-equivalent paths are different methods or strategies that yield the same emissions-reduction outcome. Link eligibility to third-party measurement, reporting, and verification; penalize greenwashing; and set a schedule for moving toward full pricing. Concurrently, pursue sectoral agreements where U.S. involvement is more likely: green public procurement for steel and cement, a unified low-carbon shipping fuel standard, and common product standards for battery supply chains. As clean-energy investments now outpace fossil fuel investments by almost two to one, aligning by product can lead to tens of billions in new factories and ports without waiting for a grand deal. If COP30 trade rules incorporate these components—price floors, border alignment with revenue recycling, and performance-based entry—the system will remain resilient to U.S. political cycles while advancing the U.S. market.

Finance, fairness, and the Global South

These are not just buzzwords. They are the cornerstones of the COP30 trade rules. These rules are designed to be fair, ensuring that all countries, regardless of their economic status, can participate and benefit from the transition to a decarbonized economy.

Any trade-focused agreement must pass a fairness test. Two figures highlight the need to redistribute some border and carbon revenues: fossil-fuel consumption subsidies still total hundreds of billions of dollars each year, even after decreasing from a 2022 peak, and total fossil subsidies on a full-cost basis reached about $7 trillion in 2022. Redirecting just a portion of that—through domestic subsidy reform and designated border revenues—would far exceed current levels of climate finance. A practical goal at COP30 is to establish a revenue-sharing rule: a fixed percentage of carbon and border revenues is directed to a fund that supports verified decarbonization by exporters in low-income countries, with straightforward access rules and quick disbursements. This is not charity; it is supply-chain insurance that lowers the cost of clean inputs for everyone.

Fairness also requires clear responsibility in trade. About a quarter of global emissions are linked to goods and services that cross borders. This means large importers are responsible for a significant share of the problem, regardless of where emissions occur. It also means exporters need reliable timelines to adapt. COP30 should back a single template for product-level carbon accounting and a digital product passport that travels with shipments. It should establish “green customs lanes” for certified low-carbon goods, cutting dwell times and financing costs. Moreover, because developing countries were promised larger transfers and frequently received less, the summit should match any new reporting burden with paid technical support and guaranteed market access for compliant firms. These trade-offs would make COP30 trade rules politically viable: wealthier buyers bear the cost of measurement, poorer producers receive cash and certainty to modernize, and everyone gets cleaner, cheaper supply chains over time.

We started with a striking figure: 28% of emissions now face a direct carbon price, yet we are still on a dangerous path. This gap does not reflect on pricing; it reflects on inconsistent rules. Markets cannot find the low-carbon frontier if borders are unclear, accounting is scattered, and finance is misaligned. Belém presents an opportunity to address this. If negotiators leave with COP30 trade rules that secure differentiated carbon price floors, align border measures with easy verification and revenue recycling, and acknowledge performance-equivalent paths for hesitant capitals, we will have progressed beyond discussion to action. The aim is not total agreement; it is a coalition large enough to make a difference and flexible enough to grow. The outcome is a world where decarbonized production wins by default because the rules encourage it in every container, invoice, and loan. Write those rules now, and the following climate statistic worth celebrating will not be yet another temperature record. It will be the share of trade that reflects the actual cost of carbon—and reduces it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Banque de France. (2020). CO₂ emissions embodied in international trade (Bulletin).

DevelopmentAid. (2025, Aug. 27). Amazon at the crossroads: Why COP30 could end in failure.

European Commission. (2025). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

International Energy Agency. (2024). World Energy Investment 2024.

International Energy Agency. (2025, Nov.). Fossil fuel subsidies—Topic page and database update.

International Monetary Fund. (2022, May 19). Why countries must cooperate on carbon prices.

International Monetary Fund. (2023, Aug. 24). Fossil-fuel subsidies surged to record $7 trillion.

Resources for the Future. (n.d.). How is the U.S. pricing carbon? How could we price carbon?

Sky News. (2025, Nov. 11). COP30 is under way – but why is it so controversial?

Snower, D. (2025, Nov. 15). Rewiring trade for a warming world: How COP30 can turn climate goals into trade rules. VoxEU/CEPR.

UNEP. (2025, Nov. 4). Emissions Gap Report 2025.

UNFCCC. (2025, Oct. 28). 2025 NDC Synthesis Report.

World Bank. (2025, Jun. 10). Global carbon pricing mobilizes over $100 billion for public budgets (Press release).

World Bank. (2025). State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2025 and Dashboard.

World Economic Forum. (2025, Mar. 3). Emissions in trade: where are they and how do we measure them?

The Guardian. (2025, Nov. 15). COP30 was meant to be a turning point—so why do some say the summit is broken?

Comment