No Reset: Takaichi’s First Moves Lock In the New Normal of Japan-China Relations

Input

Modified

Japan’s new PM locks in a hard-line, US-aligned stance Japan–China ties enter “stable instability” as ASEAN/Seoul outreach continues Schools and policymakers must harden compliance and diversify partnerships

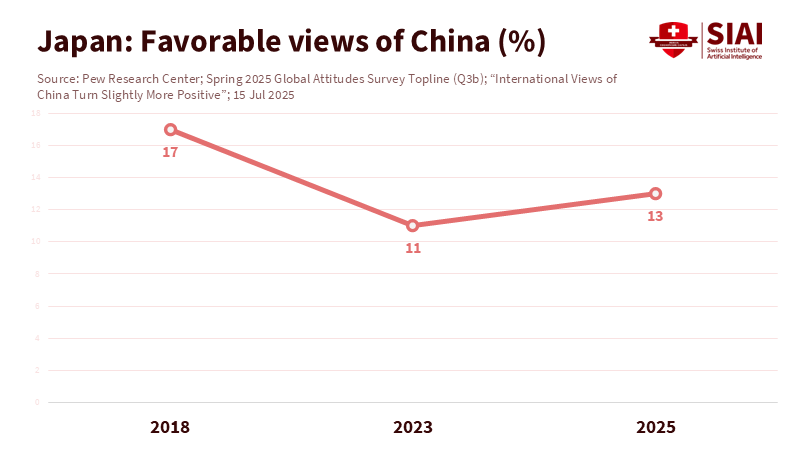

Only 13% of people in Japan view China favorably in 2025. This single number reflects the reality of Japan-China relations. It explains why a hard-line approach is widely accepted at home. It also highlights why a new prime minister’s initial actions rarely change the deeper trends. In situations of low trust, leaders focus on “stability,” while voters prefer strength. The public mood does not call for a reset; it seeks control. Early commentary anticipating a significant change in Japan-China relations misses the mark. The baseline is set. New rhetoric matters less than the structural incentives and public opinion that now oppose accommodation. The key question is not whether a leader can warm relations but how to navigate a long period of “stable instability” without errors, while ensuring safeguards for trade, education, and research that still link the two economies and societies.

Japan-China relations: the new normal

The new prime minister made a clear statement on Taiwan, describing a situation there as potentially “survival-threatening” for Japan. The response was quick. Beijing criticized the remarks, and a Chinese diplomat’s threatening post received backlash. Tokyo stood firm but maintained its position. This is not an escalation for its own sake; it reflects a growing consensus in Japan over the past decade that security risks in the Taiwan Strait are real and imminent. The political message is clear. A strong starting position sets the tone for cabinet authority, party management, and credibility in alliances. It also reassures voters that the government will not waver on key security issues. The downside is expected diplomatic friction. The upside, for supporters, is clarity.

Even amidst the tensions, both sides kept communication open. The leaders met on the sidelines of APEC and promised to pursue “constructive and stable” ties. This phrase is central to the new normal: a readiness to communicate without expecting favorable outcomes. Tokyo addressed rare earths and activities in the East China Sea. Beijing recognized the importance of maintaining open lines of communication. This managed-risk balance will characterize Japan-China relations in the near future. It accepts that deep strategic mistrust will continue, while practical matters—trade, supply chains, economic stability—necessitate ongoing, albeit tense, interactions. It is not relaxation. It is a disciplined approach to limit damage.

Importantly, tensions did not start this week, and they will not end with one meeting. The previous government already reestablished senior-level contacts with Beijing but failed to change public perceptions or erase security concerns. Those efforts created a foundation for diplomacy, not a barrier to strategic competition. The new prime minister inherits that foundation and raises the level of deterrence while keeping dialogue alive. The combination may seem more challenging because it is more explicit, rather than due to a sudden change in fundamentals.

U.S. alignment first: what changes and what doesn’t

The first summit was with Washington, not Beijing. The message was clear: the alliance is “the foundation” of Japan’s security and economic strategy, and reinforcing it is a top priority. New agreements on tariffs, critical minerals, and industrial cooperation followed. The government also emphasized that it would not reopen a large, previously agreed investment package with the United States. This represents continuity with greater urgency. It reduces ambiguity on supply chains, defense integration, and technology standards. It also establishes a precise sequence: align first with the U.S., then adjust regional outreach based on that foundation. This order clarifies incentives for firms and universities planning long-term projects, particularly in semiconductors, AI, and critical minerals. It also sends a message to the public that the government will shield the national strategy from short-term diplomatic turbulence.

The defense track tells the same story. Japan is in year three of a five-year buildup totaling about ¥43.5 trillion through FY2027, with FY2025 spending expected to increase. The program invests in standoff missiles, space and cyber capabilities, and reliable logistics. At the same time, Tokyo tightened export controls on advanced chip-making equipment starting in 2023, aligning national security with technology policy and limiting opportunities for quiet compromises with China in dual-use areas. None of this began this week—and none of it will end soon. For schools and research institutions, the implication is clear: compliance, screening, and partner due diligence will remain strict. For companies, it means that capital spending plans in defense-related sectors will continue to benefit from policy support. At the same time, reliance on China in sensitive technologies will face tighter regulations and increased scrutiny.

Mixed signals to ASEAN and Seoul

If the alliance is the anchor, Southeast Asia is the swing state of regional strategy. Tokyo and Manila signed a Reciprocal Access Agreement in 2024. The Philippines ratified it later that year, followed by Japan’s Diet in 2025. Additionally, Japan’s Official Security Assistance now funds coastal radars, RHIBs, and patrol boats for ASEAN partners. These actions support governments under pressure at sea. Still, they also push ASEAN states that would prefer to hedge rather than choose. The result is a nuanced message: strong with treaty allies like the Philippines, pragmatic with Indonesia and others, and consistently framed under FOIP-AOIP “synergy.” For ASEAN observers, this is not a repeat of U.S. policy but a uniquely Japanese approach: security assistance combined with significant economic cooperation and skills, now including an ASEAN–Japan AI co-creation initiative. The tone is firm. The offer is practical, underlining Japan's clear and consistent diplomatic communication.

Signals to Seoul are steady, although still affected by history and domestic politics. The first leader-level meeting with South Korea’s president reaffirmed “shuttle diplomacy” and ongoing trilateral cooperation with Washington. This continuity is crucial. It indicates that Tokyo will maintain a strong deterrent posture while keeping diplomatic channels open with a key neighbor. It also reduces the likelihood of mixed messages regarding North Korea and supply chain security. However, the limits are apparent: neither side is eager to revisit core historical disputes that could jeopardize ties at home. The expectation is that steady, forward-looking efforts on defense coordination, export controls, and industry collaboration can sustain relations even amidst political challenges. So far, that expectation is holding.

The education and economy lens that policymakers miss

Policy discussions often separate hard security from commerce. In Japan-China relations, these areas are intertwined. China accounted for about one-fifth of Japan’s total trade in 2024. This presence supports thousands of jobs, student exchanges, and research partnerships, but it also creates risks. Efforts to diversify away from reliance on a single country are in progress, but that won’t happen overnight. Education leaders should prepare for an extended period of dual realities: political tension and economic interaction. This means risk management must be systematic, not improvised. Universities should maintain thorough partner due diligence, enforce clear conflict-of-interest policies, and ensure that labs are aware of export controls. They should also expand student access to ASEAN and India to decrease single-market dependence while preserving beneficial and lawful ties with China.

The positive aspect is that Japan’s regional engagement now prioritizes education and research. The ASEAN–Japan summit outlined collaboration on AI, quantum technology, semiconductors, disaster health, and youth exchanges. This is not merely superficial. It offers a buffer against political disruptions. When relations with China deteriorate, programs with ASEAN can accommodate some of the interest in regional studies and internships. For policymakers, this requires consistent funding for scholarships, language initiatives, and joint labs in Southeast Asia—paired with well-managed programs in China, where risks can be mitigated. For administrators, it translates into contingency plans for urgent visa or data-transfer interruptions, along with clear student safety procedures for fieldwork in sensitive locations. The real test lies not in eloquent statements but in operational resilience when geopolitical conditions shift rapidly.

Only 13% of Japanese have a favorable view of China. In this environment, no leader will risk valuable political capital pursuing a drastic thaw. The new prime minister has opted for predictability instead of experimentation: first aligning with Washington, showing strength on Taiwan and defense, keeping communication open with Beijing, and strengthening practical ties with Seoul and ASEAN. None of this raises tensions beyond the existing levels. However, it does cement the contours of a long, narrow path between confrontation and accommodation. The challenge for educators and policymakers is to build safeguards—such as compliance, diverse partnerships, support for students, and robust research collaborations—that keep our classrooms and labs open. At the same time, diplomats navigate a relationship marked by stable instability. Japan-China relations are unlikely to improve soon, but they can be managed with discipline, clarity, and protection for both learning and the economy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press. (2025, Oct. 30). South Korean and Japanese leaders vow to improve ties …

Japan Kantei (Prime Minister’s Office). (2025, Oct. 28). Japan–U.S. Summit Meeting, Signing Ceremony, and Working Lunch (Summary).

Japan Ministry of Defense. (2025, Apr. 11). FY2025 Budget (Defense Buildup Program; total ¥43.5 trillion FY2023–FY2027).

Japan Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. (2023, Mar. 31). Press conference: Export control on semiconductor-manufacturing equipment (23 items).

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2024). China’s Economy / Japan–China Economic Relations (trade share and totals).

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2025, Oct. 30). Japan–ROK Summit Meeting (Shuttle diplomacy).

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2025, Oct. 26). The 28th ASEAN–Japan Summit (FOIP–AOIP synergy; AI co-creation initiative).

Nippon.com. (2025, Nov.). U.S. envoy slams Chinese diplomat’s threat against Japan’s PM.

Pew Research Center. (2025, Jul. 15). Views of China and Xi Jinping (Japan favorability at 13%).

Reuters. (2024, Dec. 16). Philippine Senate ratifies Reciprocal Access Agreement with Japan.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 31). Xi meets Japan’s new premier; both seek to advance ties.

Reuters. (2025, Nov. 1). Japan’s PM says no plan to renegotiate $550bn U.S. investment package.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 30). South Korea’s Lee and Japan’s Takaichi to strengthen ties.

The Diplomat. (2025, Oct. 23). Why China Is Worried About Japan’s New Prime Minister.

The Guardian. (2025, Nov. 11). Japan and China in growing row after Takaichi’s Taiwan remarks.

The Washington Post. (2025, Nov. 12). Chinese outlet lashes out at Japanese prime minister after Taiwan comments.

Comment