Getting Old Before Getting Rich: Why “Aging and Productivity” Will Reshape Education and Growth

Input

Modified

Aging erodes productivity and growth Migration buys time, not productivity—see Singapore Youthful regions gain only if they scale learning, health, and adoption

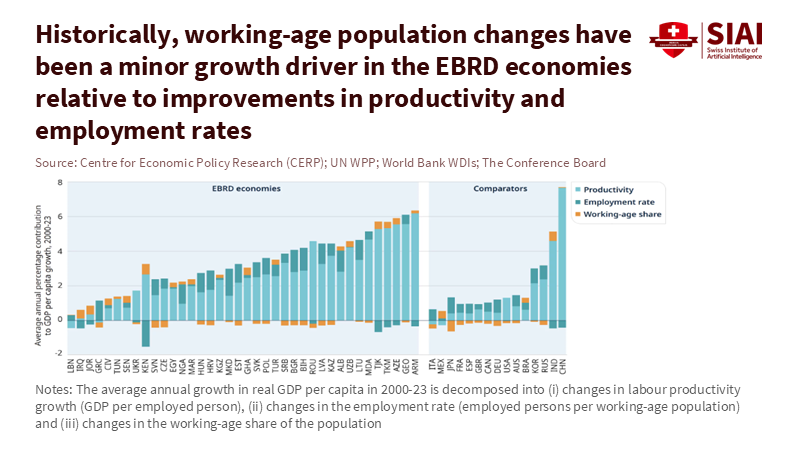

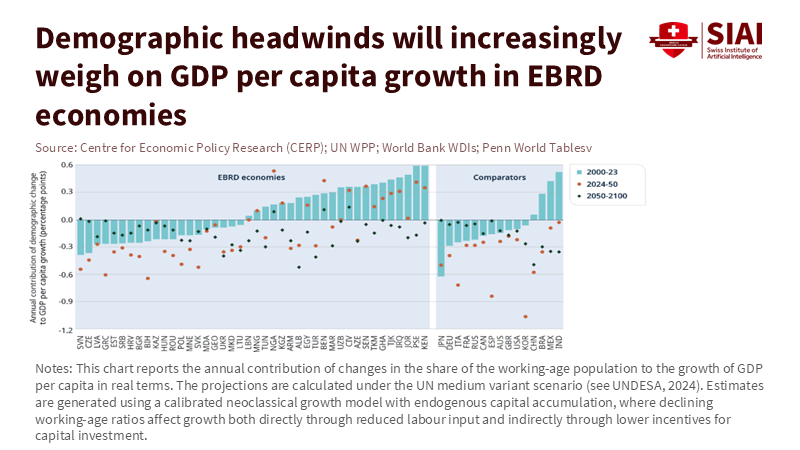

In the economies from the Baltics to the Balkans, the future has arrived early, and not in a good way. A new cross-country projection reveals that in emerging Europe, the shrinking share of working-age people will reduce average annual GDP per capita growth by 0.36 percentage points between 2024 and 2050. This statistic highlights a stark reality: aging and productivity are now intertwined policy issues that require targeted strategies. When the ratio of workers to retirees declines, capital investment slows, risk tolerance diminishes, and public budgets shift focus toward pensions and health care rather than skills and innovation. The effects are already evident. In 2023, EU labor productivity fell even as employment remained steady, indicating structural challenges rather than temporary fluctuations. Meanwhile, Japan has an old-age dependency ratio approaching one retiree for every two working-age adults, a warning for regions with similar aging trends. In this context, Eastern Europe risks “getting old before getting rich.” At the same time, some parts of Central Asia and Africa could, if they act quickly, turn their youth into an economic advantage. The key factor in each case is the relationship between aging and productivity, emphasizing the need for specific policy responses.

Aging and productivity: reframing the growth problem

Aging has often been viewed simply as a numbers issue. We once questioned if there would be enough workers to support a growing number of retirees. The bigger concern is more complex. Aging can reduce productivity growth. A detailed study tracking U.S. states over thirty years found that a 10-point increase in the share of people aged 60 and older cut per-capita GDP by 5.5%, with two-thirds of this decline attributed to slower labor productivity rather than fewer workers. The reasoning is straightforward. Older businesses and industries invest less in cutting-edge technologies. Older workforces tend to face more health challenges. Investors seek safer returns. Over time, the economy shifts toward lower-productivity services. Recent data from Europe supports this trend: productivity per person and per hour declined again in 2023, even as employment levels remained stable. This aligns with our expectations when demographics hinder the adoption of new techniques.

Some economists argue that aging can drive automation and mitigate productivity declines. There is some truth to this idea: regions that age more rapidly often adopt more robots or labor-saving technologies. However, this relies on the capacity to finance and integrate technology quickly. It’s not a given. Success depends on adaptable products and labor markets, substantial capital resources, and strong managerial and digital skills. Following 2019, Europe’s productivity gap with the United States widened, particularly in information, communications, and professional services—areas that benefit greatly from AI and data-driven processes. In other words, while aging might push companies toward automation, whether this push increases overall productivity depends on the ability of regions to foster innovation and collaborate effectively. If this spread is slow, aging and productivity reinforce each other negatively.

Singapore versus Eastern Europe: migration helps, but aging and productivity still fall

Singapore is often seen as a unique case that tackled labor shortages by welcoming workers from neighboring countries. In 2023, the city-state’s total fertility rate among residents dropped to 0.97. Yet, it continued to grow by attracting workers from Malaysia, Indonesia, and beyond. By June 2024, the number of non-residents reached 1.86 million, with over 300,000 Malaysians estimated to travel daily for work. New cross-border initiatives, including a special economic zone in Johor, aim to facilitate further movement. If migration alone could solve the aging problem, Singapore would be the exemplar. Yet even there, productivity declined: real value added per actual hour worked fell by 2.4% in 2023, continuing a drop from 2022. When a top-tier hub with strong labor inflows struggles with productivity, the takeaway is clear. Migration can provide temporary relief, but cannot replace the necessary efforts to improve overall productivity in an aging economy.

Eastern Europe confronts an even stricter version of this challenge. Many countries lack access to a large, nearby labor force for daily commuting. Instead, they have exported workers, often the young and skilled, to wealthier neighbors. Since 1990, Romania alone has experienced one of the most significant rises in emigration stocks in the EU. The outcome is a vice: fewer births, fewer residents, and more retirees. Old-age dependency ratios in some parts of the region now resemble those of Western Europe. By 2024, the EU had just over three working-age adults for every person aged 65 and older. At the same time, Europe’s labor productivity decreased in 2023, followed by a slight recovery in 2024. In simple terms, the overall baseline in Europe is already weak; Eastern Europe starts behind and is losing young talent. Without a focus on productivity, aging will hinder growth twice—first through a smaller labor force and then through lower efficiency gains.

Central Asia and Africa: a short window for an “aging and productivity” dividend

Not every region faces the same timeline. The demographic structure remains favorable in parts of Central Asia and Africa, but the opportunity is fleeting. New models indicate that Central Asia can see a minor demographic boost (~0.1 percentage points a year) through 2050 as large youth groups enter the workforce. Sub-Saharan Africa can achieve a much larger dividend (~0.37 percentage points a year) if it accelerates job creation. The logic is clear: when the share of working-age individuals increases, productivity can rise as well, provided education, health, and capital growth keep pace. That “if” carries significant weight. In various African economies, the transition from education to employment remains sluggish, firms tend to be small, and financial resources are limited. However, the potential is historic: Africa’s working-age population is expected to grow from approximately 883 million in 2024 to 1.6 billion by 2050, comprising nearly one-quarter of the global total. If policymakers and stakeholders act decisively to harness this demographic dividend, the international growth landscape could be transformed.

Central Asia’s youth demographics are also noteworthy. In several countries, over half the population is under 30, and in some regions, one-third are children aged 0–14. This can drive labor-intensive growth in the short term. However, fertility rates are dropping quickly in the area, and migration channels are already active, with most emigrants being under 35. The demographic advantage will disappear unless governments convert enrollment increases into actual learning gains and connect graduates with formal, productive businesses. This requires aligning vocational education with the data-driven tasks that growing companies handle, developing modern apprenticeship systems, and digitizing public procurement to encourage small and medium-sized enterprises to meet quality standards. Youth alone isn’t sufficient; combining youth with productivity is essential.

A policy playbook for aging and productivity

What should education leaders, administrators, and finance ministries do when they’re faced with both aging and productivity challenges? First, address preventable productivity losses in older workforces. Data from Singapore shows that chronic health issues raise costs and reduce output, with the impact increasing with age. Investing early in preventive health measures, screenings, and workplace wellness can yield returns by helping maintain high productivity levels among older workers. This principle applies broadly. In aging school systems and universities, the same strategy—early assessments, ergonomic improvements, and ongoing skill development—can help sustain teaching quality and research output. In economies where services are prevalent, healthier, longer working lives bring direct, significant benefits.

Second, accelerate the pace of technology adoption. The gap between those who lead and those who lag has grown most in sectors where digital capital enhances human capital. Europe’s poor productivity isn't mysterious; it reflects slow adoption of ICT-intensive services and limited funding for intangible assets. The solutions are also well known: stronger capital markets for risk, quicker credential portability across borders, and procurement processes that reward outcome-oriented digital upgrades in education and health. Eastern Europe, in particular, must invest in financing for data-centered companies, make adult learning more accessible and manageable, and integrate universities into local value chains to ensure research fosters adoption rather than just publication.

Third, leverage regional partnerships to enhance labor mobility and productivity. Singapore’s collaboration with Johor is an example: dedicated corridors can align skills, infrastructure, and standards to reduce search frictions and travel time. Eastern and Central European cities could replicate this model on a smaller scale by training jointly with nearby countries, fast-tracking recognition for key occupations, and establishing cross-border campuses that share facilities and faculty. The goal isn’t merely to increase cross-border movement; it’s to ensure that each hire from another country boosts firm-level productivity instead of just filling a position. If done correctly, mobility increases returns on local training by enabling skills to be utilized at the forefront.

Finally, align education strategies with demographic trends. In aging systems, shift funding towards lifelong learning, late-career re-skilling, and pathways that reduce the transition time from school to work for each cohort. In youthful systems in Central Asia and Africa, the priorities differ: focus on foundational literacy and numeracy, ensure substantial secondary school completion, and selectively expand tertiary education in STEM fields that meet real employer needs. For both groups, commit to measuring learning outcomes rather than just attendance, and gather evidence on effective programs at scale. None of this will be cheap. However, the alternative—decades of low growth—will be even more costly. The decision isn't about whether to spend or save; it's about investing for returns versus allowing stagnation.

The stakes and the timeline

It’s worth reiterating the key figure: in emerging Europe, aging will reduce annual per-capita income growth by roughly 1/3 of a percentage point through mid-century. This isn't predetermined; it's a call to align policies around the intertwined issues of aging and productivity. Western Europe demonstrates that these challenges first show up in data we often overlook—quarterly productivity declines and sluggish technology adoption in digital services—long before political responses emerge. Singapore illustrates that while migration can temporarily alleviate the problem, it cannot, in itself, drive productivity improvement. Central Asia and Africa highlight that a youth surge does not automatically translate into a demographic advantage until education, health, and financial markets do. The way forward is clear: safeguard late-career productivity, hasten technology adoption in services, design migration as skills policy, and align education reforms with each society's demographic phase. If we take these steps, regions that "aged early" can still achieve growth, while those that are still young can prosper before facing the same fate.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2017). Secular Stagnation? The Effect of Aging on Economic Growth in the Age of Automation. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings.

AP News. (2025, Feb. 27). South Korean births increased last year for the first time in nearly a decade.

Channel NewsAsia. (n.d.). Clearing the Causeway (interactive).

Eurostat. (2023, Dec. 7). GDP stable and employment up by 0.3% in the euro area and EU—productivity down y/y.

Eurostat. (2025, Mar. 27). Productivity trends using key national accounts indicators (EU labour productivity −0.6% in 2023; +0.4% in 2024).

Eurostat. (2024). Population structure and ageing—Statistics Explained (EU old-age dependency ratio 33.9% on Jan. 1, 2024; Bulgaria 38.2%).

Maestas, N., Mullen, K. J., & Powell, D. (2023). The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force, and Productivity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics.

Marsh & McLennan / Mercer. (2017). Aging Workforce: Cost and Productivity Challenges of Ill-Health in Singapore.

Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore. (2025, Feb. 14). Economic Survey of Singapore 2024 (productivity reversed decline; 2023 contraction noted).

Monetary Authority of Singapore / Government of Singapore. (2023–2024). Economic Survey of Singapore—Chapter on Labour Market and Productivity (real value-added per actual hour worked −2.4% in 2023).

OECD. (2025). OECD Employment Outlook—Japan Country Note (old-age dependency ratio ~49% in 2024; trajectory).

OECD. (2025). OECD Economic Surveys: European Union and Euro Area 2025 (structural productivity constraints).

Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore—National Population & Talent Division. (2024). Population in Brief 2024 (resident TFR 0.97 in 2023; non-resident population).

UN DESA—United Nations Population Division. (2024). World Population Prospects 2024 (global and regional demographic projections).

UN Economic Commission for Africa. (2024, Jul. 12). As Africa’s population crosses 1.5 billion, the demographic window is opening (working-age population to 1.6B by 2050).

UNICEF (Europe & Central Asia). (2025). Generation 2050 in Central Asia (youth shares; demographic dividend framing).

VoxEU/CEPR. (2025, Dec. 3). Demographic change: Headwinds for economic growth (0.36 pp drag in emerging Europe; 0.10 pp dividend in Central Asia; 0.37 pp in sub-Saharan Africa)

Comment