The Subsidy Spiral Is Now a Talent Test

Input

Modified

Asian subsidies—especially in steel—distort prices and trade Make subsidies conditional on training and shared curricula Compete on skills to cut tariffs and lift productivity

Two numbers tell the story. Global steel overcapacity could reach 680 million tonnes in 2025. G20 trade restrictions now cover goods worth about $4 trillion in annual imports. These figures show a world moving away from open competition and toward rule by subsidy and retaliation. Asian industrial subsidies are at the center of this shift, with the steel sector showing the most visible pressure. The outcome is a race to lower prices and an increase in public funding. If education systems do not change, policies will continue to reward the cheapest energy and the most significant grants rather than the most valuable skills. The way forward is to shift subsidies from price tools to training contracts, offering a strategic opportunity to build a resilient, skilled workforce. Ministries and universities face a clear choice: equip students to succeed in a skills competition or watch fiscal power support factories while talent pipelines dry up.

Asian industrial subsidies and the steel squeeze

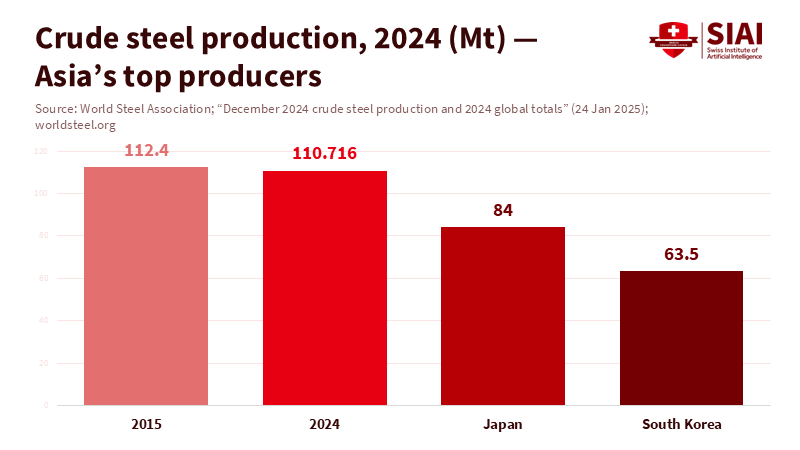

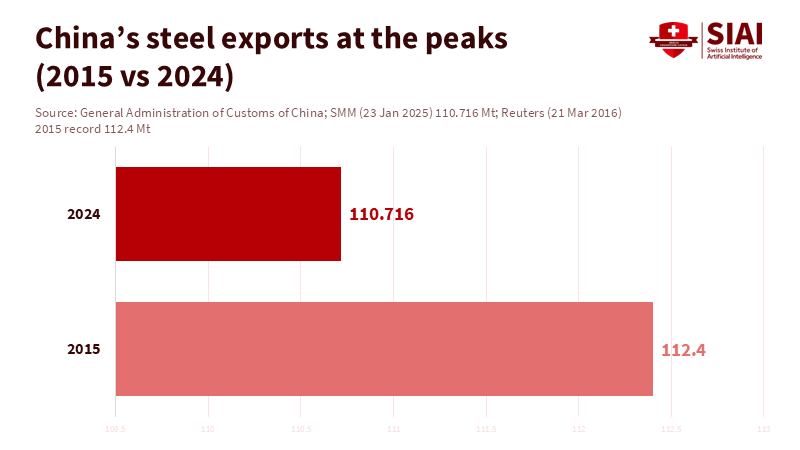

Steel illustrates how subsidy logic operates. In 2023, China produced about 1,019 million tonnes of crude steel, more than seven times India’s output and twelve times Japan’s. Chinese steel exports are expected to reach a record of around 118 million tonnes in 2024. This volume meets weak demand in Europe and elsewhere, pushing prices down and leading to defensive tariffs that raise costs for everyone. Overcapacity looms as the hidden force in the system. The OECD warns that spare capacity could exceed 680 million tonnes this year, mainly concentrated in Asia and the Middle East. These figures shape policy decisions. When price drops stem from subsidized capacity, importing countries reach for countervailing duties, carbon border fees, or “local content” rules. The cycle perpetuates itself.

Defensive actions are increasing. The European Union is gradually introducing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism through 2025 and will start charging in 2026. This measure will affect carbon-intensive imports, such as steel. It also imposed countervailing duties on Chinese battery-electric vehicles in late 2024. Meanwhile, the United States raised Section 301 tariffs on Chinese EVs to 100 percent in 2024. Across Asia, governments are actively involved. Japan’s “GX” initiative is now linking procurement and subsidies to boost green steel; for instance, JFE secured up to JPY 104.5 billion for an electric-arc conversion program. India expanded its Production-Linked Incentive scheme for specialty steel in 2025 to increase domestic production. South Korea’s “K-Chips” policy raised investment tax credits for strategic manufacturing through 2025. In the West, price protections meet capacity, and cash in the East, leading everyone to escalate.

From price wars to skills wars: redirecting subsidies

The current approach views subsidies as tools to increase volume or as barriers to imports. This mindset ignores the absolute scarcity: advanced skills. Asia’s education systems already produce talent at a large scale; China alone expects about 12.22 million college graduates in 2025 and now grants more STEM doctorates than the United States. However, “scale” does not equal “fit.” Steelmakers aiming to decarbonize require metallurgists to develop DRI-H2 methods, electrical engineers skilled in power electronics, and data scientists to manage mill-wide control models. Public funding often prioritizes equipment and tax incentives over building these talent pipelines. If subsidies continue without significant human-capital conditions, the result will be cheap output and costly gaps in retraining. A skills competition—quiet, gradual, and decisive—will determine whether subsidy funds lead to productivity or merely buy time.

An education-linked industrial policy can break this pattern. Instead of subsidizing capital alone, pair each award with verified training, apprenticeship hours, and co-designed curricula. Use CBAM-style disclosure logic to require companies benefiting from subsidies to report skill creation alongside emissions reductions. Fund quick “bridge” programs that help mechanical engineers transition into hydrogen, power systems, and plant AI. Japan’s reskilling agenda and broader GX policy framework illustrate how to build this layer. Meanwhile, Korea’s substantial 2025 R&D and AI budgets provide a model for connecting public spending with talent needs. If we shift the goal from defending prices to expanding capabilities, “industrial subsidy” becomes “education contract.” This change can lower retaliation risks and improve long-term returns on public funds, fostering a sense of achievable progress and confidence in policy innovation.

Design rules that make subsidies teach

There is no need to guess what works. The OECD’s recent findings on industrial subsidies highlight two recurring problems across sectors: unclear support for state-linked firms and poor reporting on market impact. Both issues lead to global price distortions and prompt more trade defenses. Education-linked design rules can address both. First, limit the share of any single subsidy that can be used for equipment and mandate a fixed portion for accredited training outcomes. Second, require recipient firms to disclose training results in the same way they report emissions or safety. Third, prioritize awards where groups of firms, universities, and technical colleges jointly manage curricula and lab facilities. These rules encourage subsidies to yield returns in human capital rather than just output. Clear, transparent rules will build trust among policymakers and industry, making the system more effective and sustainable.

Steel again provides a key example. The EU’s CBAM is an emissions tool. Still, its compliance timeline creates a clear training timeline for Asian exporters aiming to keep market share. Green-steel labels being discussed in Europe would reward mills that can certify low-carbon processes and quality. Japan’s GX policies and early green-steel procurement commitments provide domestic demand signals linked to broad reskilling. At the same time, India’s updated PLI for specialty steel aims to enhance the product mix along the value chain. If ministries pair these demand signals with shared testbeds and consistent competency standards—such as operator certifications in hydrogen safety or mill-wide AI—then “subsidy” becomes a sign of workforce strength. The alternative is a stagnant subsidy race that depletes resources and encourages more tariffs.

What schools and ministries do next

Universities and technical colleges are crucial. They can form “skills agreements” that translate subsidy announcements into classroom achievements. Start with steel and expand to batteries, power equipment, and semiconductors. For steel, align courses with three immediate needs: hydrogen handling and safety, digital twins for process control, and advanced materials for low-carbon metallurgy. Ministries can create a short list of CBAM-aligned competencies with exam standards and fund joint positions with mills. Companies should commit to train-to-hire ratios and report results annually. This model is adaptable. Korea’s increased R&D and AI funding support programs that integrate plant operations with machine learning. Japan’s reskilling funds can support industry-led modules in technical colleges. India’s PLI revisions offer a chance to establish “make-in-India, teach-in-India” partnerships that export not just steel but skills. Every move pushes Asian industrial subsidies toward developing capabilities instead of price battles.

Policy leaders also need to lower the intensity of the subsidy debate abroad. It’s helpful to distinguish between price and capability. Tariffs respond to price, while standards address capability. The more subsidy awards are linked to measurable, transferable skills, the easier it becomes to negotiate mutual recognition and avoid retaliatory actions. The WTO’s latest report on trade-restrictive measures shows that the stockpile is still growing; even with temporary agreements, the underlying trend leads toward more barriers. By moving from “protect output” to “grow skills,” Asian governments can defend their industries while reducing triggers for foreign retaliation. Steel will continue to be contested; however, when the focus shifts to the number of newly certified hydrogen operations technicians rather than the size of a grant, the political landscape changes. The economy does too.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Biden White House. (2024, May 14). Fact sheet: President Biden takes action to protect American workers and businesses from China’s unfair trade practices.

European Commission. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism. EUR-Lex.

European Commission. (2024, Oct 28). EU imposes duties on unfairly subsidised electric vehicles from China. Press release.

European Commission. (n.d.). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

India Briefing. (2025, Jan 7). India updates specialty steel PLI scheme.

Kim & Chang. (2024). Government’s key semiconductor industry policies for 2024.

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (Japan). (2024). Third report on new industrial policy direction (includes reskilling budget).

Nippon Steel. (2025, Mar 13). GX initiatives investor presentation.

PwC. (2025). Korea, Republic of — Corporate tax credits and incentives (updated July 25, 2025).

Reuters. (2024, Nov 14). Record number of students to graduate college in China in 2025.

Transition Asia. (2025, Sep 29). 2025 sustainability report updates: JFE Holdings (GX support up to JPY 104.5 bn).

World Steel Association. (2024). World Steel in Figures 2024 (country outputs).

World Steel Association. (2025, Jan 24). December 2024 crude steel production and 2024 totals.

WTO. (2025, Nov 13). Report on G20 trade measures (mid-Oct 2024 to early 2025).

OECD. (2025, May 28). The market implications of industrial subsidies. TAD/TC(2025)7/FINAL.

OECD. (2025). Steel Outlook 2025 (exports and capacity trends).