Trump’s Tariffs and the Quiet Rise of Southeast Asia Manufacturing

Input

Modified

Trump’s tariffs are driving factories and capital from China into Southeast Asia ASEAN is gaining ground in high-tech exports and global manufacturing Education and skills will decide whether this shift creates lasting, quality jobs

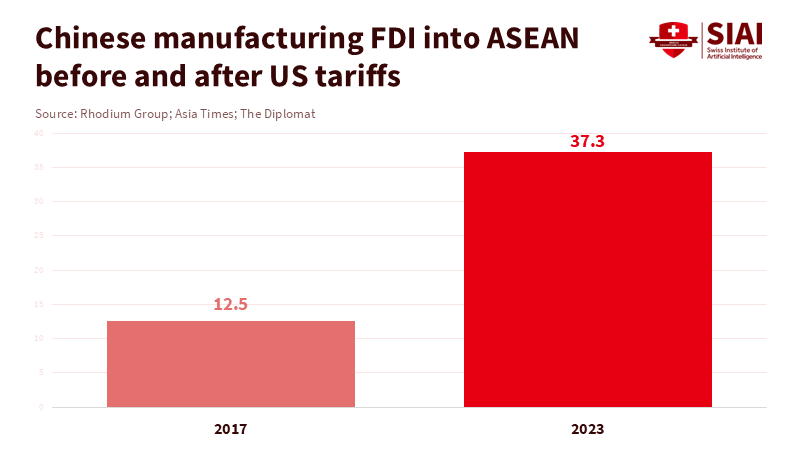

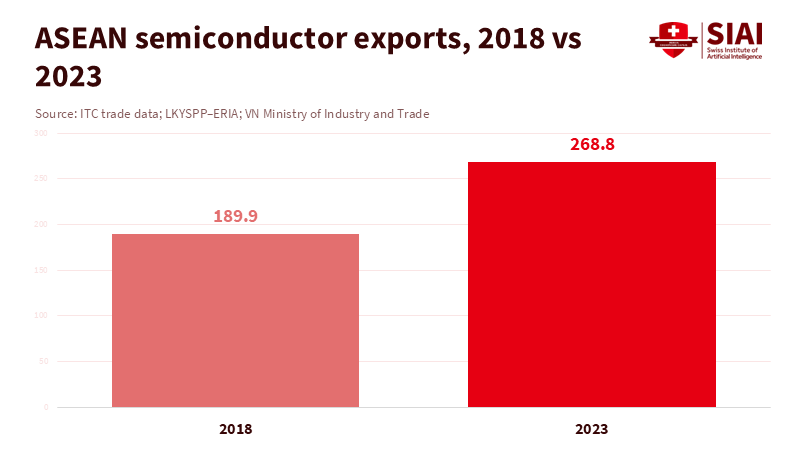

Between the first round of Trump tariffs and “Trump 2.0,” an overlooked turning point occurred. Chinese manufacturing investment in ASEAN jumped from about US$12.5 billion in 2017 to US$37.3 billion in 2023, nearly tripling in six years. At the same time, Southeast Asia’s semiconductor exports increased to US$268.8 billion in 2023, accounting for roughly 24-25% of global exports. These changes are not just byproducts; they signify a significant shift. Section 301 duties now cover around US$370 billion of Chinese exports to the United States, with tariff rates ranging from 7.5 to 25 percent. Washington has imposed steeper tariffs on key products, including electric vehicles and batteries. In contrast, after lengthy negotiations in 2025, most Southeast Asian countries secured reciprocal tariffs of around 19 to 20 percent, significantly lower than the initial threats that approached 40 percent. Combined, these figures reveal a straightforward truth: Southeast Asian manufacturing has become the primary escape route from Trump’s tariff wall and is the most likely successor to China’s role as the world’s factory over the next decade.

The main point is clear. Trump’s tariff strategy, especially in its later phase, may hurt Chinese exporters. Still, it also serves as an industrial boost for Southeast Asia's manufacturing. It pushes factories, investment, and training away from China and into ASEAN, where tariffs are lower, trade agreements are stronger, and the workforce is younger. Over time, this shift doesn’t just change trade flows; it transforms the landscape of classrooms, vocational institutes, and corporate training budgets. For educators and policymakers, the key question is no longer whether this shift will occur. It is about turning this almost certain relocation of production into a broad improvement in skills and institutions, rather than another cycle of low-wage competition.

Tariffs that push factories south: Southeast Asia manufacturing’s opening

The starting point is the tariff gap itself. Since 2019, US Section 301 measures have imposed additional duties of 7.5 to 25 percent on about US$370 billion of Chinese imports. The official review in 2024 concluded that these tariffs reduced China’s share of US imports for targeted products by more than 9 percentage points between 2017 and 2023, benefiting countries such as ASEAN members, Mexico, and India. The message to businesses is clear: exporting directly from China to the US has become a long-term liability. When “Trump 2.0” revived the notion of imposing larger tariffs and suggested even higher rates on strategic goods, that message became urgent.

Southeast Asia manufacturing provided a ready alternative. Analyses based on Rhodium Group data show that Chinese manufacturing foreign direct investment (FDI) in ASEAN soared from US$12.5 billion in 2017 to US$37.3 billion in 2023, making ASEAN the primary destination for Chinese companies looking to expand their manufacturing footprint. Rhodium analysts state that US tariffs on China since 2017 have been a key reason for this increase, as companies shift supply chains through ASEAN to maintain access to the US market. This isn’t a case of abstract diversification; it involves actual factories, warehouses, and training centers relocating from China to industrial parks in Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Trump’s second term solidified this trend by granting Southeast Asian countries their own, lower tariff rates. The Asia Media Centre reported on the 2025 “reciprocal tariffs” deal, noting that initial US proposals threatened tariffs as high as 46 percent on some Southeast Asian exports. After months of negotiation, most governments obtained final rates around 19 to 20 percent, while “transshipped” Chinese goods labeled as ASEAN-made still face penalties exceeding 40 percent. The result is a clear hierarchy. Goods from China face old Section 301 duties in addition to new surcharges on items such as electric vehicles. Meanwhile, genuinely local Southeast Asia manufacturing faces lower, yet still significant, tariffs—low enough to keep the US market accessible but high enough to promote regional value addition. This tariff structure is precisely what companies evaluate when deciding whether to upgrade a Chinese plant, build a new line in ASEAN, or relocate production to the United States.

For the education sector, this goes beyond trade policy. The tariff system shapes where new apprenticeship programs will be established, where internships in automotive software will be offered, and where future factory managers will develop their skills. Each relocated electronics factory brings in-house training programs, supplier development initiatives, and partnerships with local colleges. When these factories settle in Southeast Asia rather than in inland China or the US Midwest, the opportunities for growth shift accordingly.

From ‘factory of the world’ to shared workshop: China and Southeast Asia manufacturing

China still leads in global manufacturing. Estimates from the World Bank and CSIS suggest that China’s manufacturing value added reached around US$4.7 trillion in 2023–2024, roughly 28-30 percent of the world's total, far exceeding the combined output of the United States, Japan, and Germany. Manufacturing still makes up over a quarter of China’s GDP, well above the global average. This base will not vanish in the next ten years. However, it increasingly focuses on high-end sectors, such as advanced machinery, electric vehicles, batteries, and other cutting-edge industries, which Beijing heavily supports through industrial policy. Simultaneously, years of investment have left China with excess capacity across many mid-range sectors, putting pressure on profit margins and prompting companies to seek cheaper production locations abroad.

Southeast Asia's manufacturing occupies an advantageous position. It offers lower wages than coastal China, improved infrastructure, and a network of trade agreements linking ASEAN to major markets. This combination is reflected in export data. Official and industry reports from Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade and regional trade agencies indicate that ASEAN’s semiconductor exports reached US$268.8 billion in 2023, about 23.6 to 25 percent of global semiconductor exports, after growing 41.6 percent from 2018 to 2023. Analysts from Rhodium and others report that Vietnam’s share of global consumer electronics exports rose from 8.3 percent in 2017 to 10.4 percent in 2023 as major companies moved assembly operations from China to the region. While these changes may seem small compared to China’s massive figures, they are significant because new capacity leads to the development of new skills and ecosystems.

Vietnam exemplifies both the opportunity and the challenge. Reports from Reuters show that exports to the US reached US$142.4 billion in 2024, making up about 30 percent of Vietnam’s GDP, primarily driven by electronics and other manufactured goods produced by companies that relocated from China after the initial Trump tariffs. The same sources note that new US tariffs of 20 percent on Vietnamese goods and up to 40 percent on incorrectly labeled Chinese products have already affected growth forecasts. Yet even with these challenges, foreign investment in manufacturing continues to climb, and electronics exports set new records in 2025. The situation is clear: tariffs can slow but not halt the profound restructuring of production networks. For most multinational companies, moving from China to Southeast Asia manufacturing is now a strategic safeguard, not a temporary trial.

Looking ahead, the most likely scenario is a shared workshop model. China will maintain its position as the primary hub for high-tech and scale-intensive production. At the same time, Southeast Asia manufacturing will take on much of the incremental low- and mid-range capacity and an increasing share of complex tasks, especially in chips, electronics, and green technology. New foreign direct investment, rather than old capital, will determine how much ASEAN’s share increases. Education systems that can supply this added capacity with skilled workers will tilt the balance in their favor.

Skills, schools, and the human side of Southeast Asia manufacturing

A tariff schedule alone cannot train a technician. The real competition lies in who can turn the relocation of factories into a transformation of high-quality learning. ASEAN’s population of 680 million, more than 65 percent of whom are under 40, provides a vast potential labor pool. Chinese investment and Western “China plus one” strategies are shaping that pool into a target for corporate training programs. Each new electronics cluster near Ho Chi Minh City or Penang requires line leaders who can solve process issues, engineers who can adapt global designs to local needs, and managers who can navigate both US compliance and Chinese supplier networks.

For educators and administrators, this transition requires a new perspective. Vocational systems in many ASEAN countries were established for light manufacturing and services, not for complex semiconductor packaging or electric vehicle battery assembly. Yet the data on foreign direct investment and exports indicate that these high-tech industries are precisely where Southeast Asia's manufacturing is expanding the fastest. Colleges and training centers that continue to offer generic “electrical” or “business” courses risk missing a crucial opportunity. Instead, there is a strong case for modular, adaptable programs designed around real industry needs, such as surface-mount technology, quality analytics, energy-efficient factory operations, and digital inventory management. Collaborations with incoming Chinese, Korean, and Western firms can transform their training materials into joint curricula, with credits recognized towards national qualifications.

China faces a related challenge. Domestic policy remains heavily focused on manufacturing, with official reports showing that the sector produces about 30 percent of global manufacturing value added. Yet as mid-range activities move to Southeast Asia manufacturing hubs, millions of Chinese workers risk being left behind in shrinking plants or low-growth regions. Retraining every displaced worker to become a battery engineer or AI specialist is unrealistic. Instead, Chinese education planners may need to invest in broad, transferable skills—industrial digital skills, cross-border logistics, English, and regional languages—that enable workers to follow companies into new markets or pivot to higher-productivity services connected to trade and manufacturing.

There is also a social aspect. When factories relocate, communities lose not only jobs but also the implicit knowledge of production processes. For ASEAN, receiving that knowledge can enhance local innovation over time, especially if universities and applied research centers connect with industrial clusters. For China, the danger is a gradual decline in mid-level technical expertise outside a few key regions. Cross-border educational partnerships—joint institutes between Chinese universities and ASEAN colleges, shared online course platforms, and regional skills competitions—could help mitigate the consequences and encourage more balanced integration. These are not trivial additions; they represent the educational framework of the new production landscape.

Policy choices in a Trump 2.0 world

Skeptics argue that Southeast Asia's manufacturing is merely a staging ground for Chinese goods and that US scrutiny of transshipment will eventually undermine it. The US has indeed become more aggressive: reports indicate that the US is pressuring Vietnam to reduce the use of Chinese technology in goods headed for the US, with threats of tariffs up to 46 percent if changes are not made. New enforcement tools on rules of origin and supply-chain transparency will make simple “label swapping” much harder. However, the structure of investment suggests something more sustainable is happening. Chinese firms are not only rerouting shipments through ASEAN; they are establishing full-scale operations, while ASEAN governments negotiate lower tariff bands in exchange for opening their markets to US exports. Even amid periodic disruptions, the fundamental dynamics of cost, proximity, and policy incentives indicate a shift toward more regionalized production centered in Southeast Asia.

For policymakers in ASEAN, the potential and the risks are significant. If they treat Trump’s tariffs as a mere windfall, Southeast Asia manufacturing could remain a low-cost accessory to Chinese supply chains, vulnerable to future trade shocks. But suppose governments tie investment incentives to commitments on local training, technology transfer, and research and development collaboration. In that case, the region can advance up the value chain within a decade. This means requiring major investors to co-fund vocational centers, share training content, and assist in upskilling teachers. It also involves strengthening regional frameworks—through ASEAN agreements and new free trade agreements—that acknowledge skills across borders so workers can move with demand, rather than being trapped in national labor markets.

Education ministries and institutional leaders have clear options to consider. They can adjust curricula to match sectors growing under the tariff regime, such as semiconductors and green industrial equipment. They can promote dual-education models that divide time between classrooms and factories in key manufacturing hubs in Southeast Asia. They can also support research on how relocation affects communities in both China and ASEAN, providing policymakers with better evidence to help those who may lose out and promote inclusive gains. Most importantly, they can ensure that trade and industrial strategies prioritize human capital from the outset, rather than treating it as an afterthought.

The initial numbers indicate a clear trend: Chinese manufacturing investment is moving into ASEAN, and Southeast Asia's share of global high-tech exports is increasing rapidly. These shifts aren’t solely due to Trump’s tariffs, but the tariff regime has intensified this trend, making “China plus one” evolve into “China through Southeast Asia” for many firms. Over the next ten years, this trend is expected to position Southeast Asia's manufacturing as the primary driver of global factory capacity growth, even while China remains the largest producer. Educators and policymakers now face a decision: should they view this as a temporary trade issue or as a significant shift for the future? If they act quickly—linking tariffs to training, foreign direct investment to skills, and regional integration to shared curricula—what has emerged from Trump 2.0 can become a purposeful development strategy. If they don’t act, the new factory landscape will still form. Still, the benefits will be limited, uneven, and difficult to adjust after the machinery is set up.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asia Media Centre. (2025). OTR: How Southeast Asia Negotiated Lower US Tariffs.

Asia Society Policy Institute. (2023). Balancing Act: Assessing China’s Growing Economic Influence in ASEAN.

Cargoson. (2025). How Big Is the Manufacturing Industry?

China Briefing / Dezan Shira & Associates. (2025). China Manufacturing Industry Tracker 2024–25.

ChinaPower Project, CSIS. (2025). Measuring China’s Manufacturing Might.

Diplomat. (2025). “China Plus One” Should Be a Strategic Win for America in Southeast Asia.

Fulcrum / ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. (2025). ASEAN’s Regional Ambitions for the Semiconductor Industry.

Rhodium Group. (2025). China and the Future of Global Supply Chains.

Rhodium Group. (2025). China’s Manufacturing FDI in ASEAN Grew Rapidly, But Faces Tariff Headwinds.

U.S. International Trade Commission / USTR. (2024). Four-Year Review of Actions Taken in the Section 301 Investigation.

U.S. Trade Representative. (2024). Section 301 Tariffs on China – Background and Updates.

Vietnam Ministry of Industry and Trade. (2024). The Potential of the Semiconductor Industry and ASEAN’s Position.

VietnamPlus / Vietnam Customs. (2025). Electronics Exports Hit Record High Despite Global Trade Headwinds.

World Bank. (2025). Manufacturing, Value Added (% of GDP) – China.

World Trade Organization. (2024). Trade Profiles and TiVA Database – Vietnam and ASEAN.

Reuters. (2025). Vietnam’s US Exports Account for 30% of GDP, Making It Highly Vulnerable to Tariffs.

Reuters. (2025). World Bank Cuts Vietnam’s Growth Forecast as Tariffs Bite.

Reuters. (2025). US Pushes Vietnam to Decouple from Chinese Tech, Sources Say.

Reuters. (2025). China’s Next Economic Shift Is Primed for Backlash.