Stop Calling It a Free Lunch: Why Biotech Spillovers Make Everyone Safer

Input

Modified

Biotech knowledge spillovers cut global wait times for lifesaving therapies Rich countries gain when diffusion is designed, priced, and measured—not blocked Universities and funders should hard-wire reciprocity, open methods, and cross-border teams

It takes, on average, 8 years for a drug to go from its first global launch to its arrival in low-income countries. Upper-middle-income markets wait around 4.5 years, while high-income markets wait about 2.7 years. The line is long, and the stakes are life-or-death. Yet, the same system that creates these gaps also shares ideas quickly. Biotech knowledge spillovers transfer methods, data, and skills across borders faster than products can ship. Research starts in one lab and gets refined in another; a preprint in Boston helps shape a trial protocol in Bangalore; a PhD student in London rewrites code used in Lagos. The real question is whether rich countries should view these spillovers as a "free lunch" for poorer countries or as the driving force behind their own discovery pipelines. If we see biotech knowledge spillovers as leaks to be fixed, we will slow down cures everywhere, including at home. If we plan for them, we can reduce that eight-year wait.

The hidden exposures of biotech knowledge spillovers

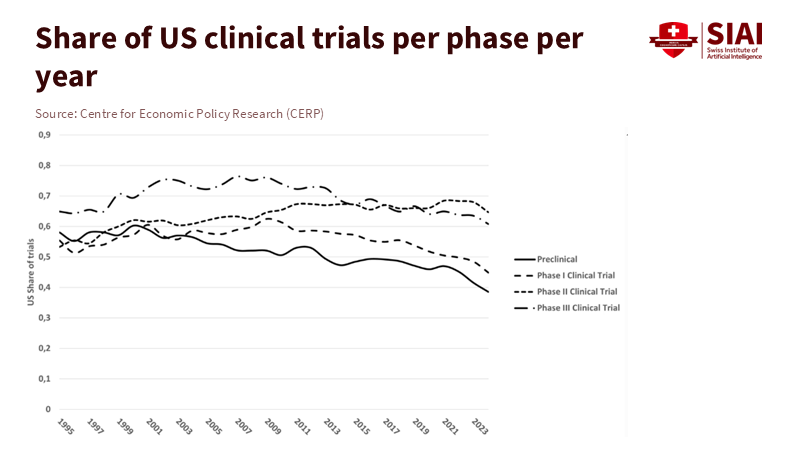

Trade economists have a helpful term for unseen connections: hidden exposures. A recent analysis shows that 3.6% of firms' costs come from Chinese imports, with about 60% of this exposure being indirect, through domestic suppliers rather than direct imports. What seems self-sufficient is actually a web of connections. The same idea applies in research. A lab may look national; its ideas are not. Over the past fifty years, scientific work has become increasingly international. In 2023, 27% of publications in OECD countries had co-authors from multiple nations, up from 22% a decade earlier. While that share has leveled off in some areas, the global trend is clear: discovery is a team effort that crosses borders. Disruptions that hinder collaboration do not just limit foreign access to knowledge; they also reduce domestic "round-trip" benefits that come back as better methods and stronger science.

Hidden exposures also involve people. The United States relies heavily on internationally trained talent to drive discovery. In 2021, about 45% of U.S. workers with doctorate degrees in science and engineering were born outside the U.S., with India and China being the most common countries of origin. On campuses, international enrollment bounced back to nearly 1.2 million students in 2024/25. These students and scholars do not take jobs from those at home; they keep labs open, courses running, and grant projects on track. When policies restrict visas or cool collaboration, they shrink the very network that turns public research and development into usable therapies. "Relocation risk" is not just about factories; it also involves the flow of minds carrying valuable knowledge across institutions.

What the numbers say about biotech knowledge spillovers

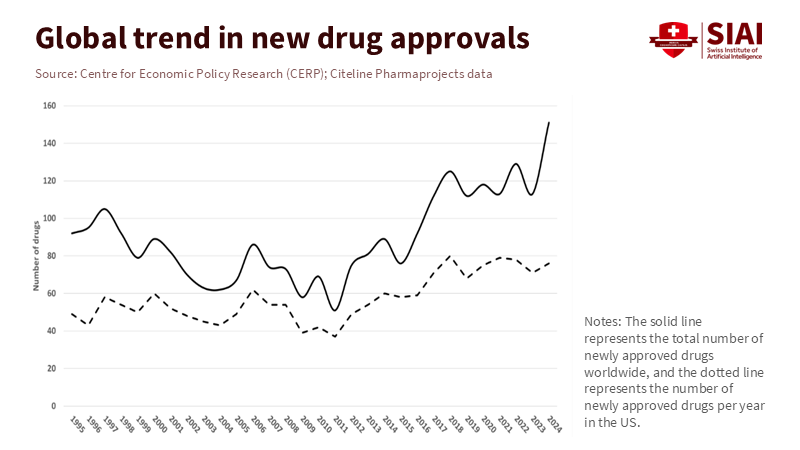

Markets drive innovation. North America accounted for about 55% of global pharmaceutical sales in 2024. Nearly two-thirds (about 67%) of sales of medicines launched between 2019 and 2023 were in the U.S., helping fund research and development. However, knowledge creation is no longer confined to a single area. Asia accounted for around 70% of global patents granted in 2023, with China alone accounting for about 46%. In other words, demand from rich countries and a growing international base of innovation now work together to drive progress. Treating spillovers as a loss overlooks this mutual exchange: buyers in the U.S. and Europe gain more opportunities, while labs in Asia, Europe, and America gain access to ideas that increase the chances of success.

Spillovers are not just broad trends; they lead to measurable improvements in the quality of ideas themselves. In the pharmaceutical industry, patents developed with international partners have a greater impact. One recent study found that patents co-developed across national borders experience an average 4.9% increase in quality (measured by forward citations). Another analysis, involving 34,964 patent families, showed that patents with international inventor teams receive about 15% more forward citations than those without cross-border collaboration. These effects may seem small individually. However, across an extensive portfolio of projects, even a few percentage points in expected impact can significantly increase the likelihood that a new target, platform, or manufacturing method succeeds.

Spillovers also depend on mobility and access. Universities are at the center of this system. International students—especially in STEM fields—support research groups and help spread best practices. Their role is both economic and scientific: international students contributed roughly $43 billion to the U.S. economy in 2024–25 and supported about 356,000 jobs. This spending keeps graduate programs and essential facilities running, which in turn supports discovery. The network effect is real: a robust influx of students increases the likelihood that a method published today will become routine, speeding up trials next year.

However, the issue of equity persists. As mentioned earlier, low-income countries wait, on average, eight years for access to new essential medicines, while lower-middle-income countries wait nearly seven. The initial launches still cluster in a few wealthy markets. These delays do not prove that rich countries "lose" from spillovers; instead, they highlight the need for faster, more widespread spillovers worldwide. Knowledge that flows easily helps close gaps in time-to-use, even when pricing and regulatory processes delay the final step. Open protocols, shared data, and joint trials shorten the learning curve. The quickest way to reduce eight-year delays is not to hoard research but to ensure that more labs in more locations can build on the same advancements.

Policy design for fair returns without choking biotech knowledge spillovers

It's understandable to fear that tax-funded science becomes a free lunch for foreign nations. Budgets are tight, and research growth slowed in real terms in 2023 across many OECD countries. However, the solution is not to restrict diffusion. Instead, we need to reconfigure incentives so that domestic taxpayers receive a clear return while keeping the knowledge network open. One initial step is to include "reciprocal access" clauses in major grants related to platform technologies. If a publicly funded team shares a pre-clinical protocol, partners in low- and middle-income countries that adopt it should automatically be included in downstream trials or manufacturing teams. This clause does not transfer intellectual property; it guarantees participation in return for visible contributions to validation, safety, or scaling up. Policymakers can implement this in NIH-funded groups. With NIH funding roughly steady at about $48 billion under a continuing resolution in 2025, the trade-off isn't about new funds but better rules for participation and credit.

Second, we should measure the spillovers we want to capture. When the U.S. or EU provides funding for translational platforms—like biomanufacturing scale-up, computational drug design, or genomic reference panels—investments could include "spillover performance" metrics. These could track the share of outputs (datasets, assays, code) used by outside teams within 12 months, the number of co-authored studies or co-filed patents with partners in developing regions, and the time it takes to replicate important methods in external labs. These are not vague goals. Publication databases, patent office records, and repository logs can all be used to assess them. WIPO's indicators already monitor international filing and co-invention patterns frequently; OECD's scoreboard tracks cross-border innovation flows. By linking a portion of milestone payments or indirect cost rates to meeting these diffusion benchmarks, we reward labs that make their work accessible.

Third, we must channel returns without limiting movement. Governments concerned about subsidizing foreign competitors should expand the use of indemnified prize contracts and outcome-based advance market commitments (AMCs) for neglected targets. Prizes and AMCs reward results, not the team's location. At the same time, guarantees can require open methods and shared manufacturing plans as deliverables. If a multinational team achieves a pathogen target faster because a Kenyan or Vietnamese lab improved the assay, taxpayers receive the outcome they funded; the spillover becomes part of the design, not an afterthought. This strategy maintains the collaborative advantage that enhances patent quality and scientific impact while ensuring a clear return on public investments.

Finally, we need to safeguard the network against over-securitization. Since 2018, the global collaboration rate has stagnated and dropped in several fields between the U.S. and China. Some risk assessment is necessary, especially for dual-use technologies. However, blanket restrictions can weaken the system. A targeted, risk-tiered research security framework—focused on project-specific threat evaluation rather than nationality—can protect valuable connections while addressing genuine concerns. The policy goal should be straightforward: keep biotech knowledge spillovers high where risks are low, and introduce safeguards where risks are real.

What this means for universities and classrooms: embed biotech knowledge spillovers by default

Administrators should facilitate spillovers rather than treat them as random occurrences. A practical step is to fund "co-supervision pipelines" with partner universities in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America for essential lab and computational methods. Link dissertation milestones to shared code repositories, mirrored data storage, and dual-site validation for key assays. This is not just charitable; it's a wise investment. When methods are validated in multiple settings by diverse teams, they generalize better, move faster into trials, and encounter fewer failures. Nature Index and national S&T dashboards can help identify potential partners; start there, then build lasting connections in areas where local disease burdens or sample diversity enhance global scientific outcomes.

Educators can integrate "spillover-ready" practices into the curriculum. Teach regulatory science alongside biostatistics. Make protocol writing and reproducibility graded, public assignments. Use preprints as live course material and require students to submit replication packages. Above all, keep the classroom international. Evidence shows that international students bolster research capacity and introduce new techniques that spread quickly. Their presence is not merely cultural enrichment; it is essential to the discovery process. Losing them would weaken core labs and diminish the impact of the knowledge they create. The economic benefits are substantial—tens of billions in the U.S. alone—but the scientific value is even greater.

The eight-year wait is an issue that should capture attention. It shows that, while we debate who pays and who benefits, those at the back of the queue are still waiting. Biotech knowledge spillovers do not create that wait; they are the most effective tool we have to reduce it. The data is precise: international teams produce higher-impact patents and papers, international students and scholars maintain research momentum, and markets that reward innovation facilitate the development of new products. Wealthy countries should not fear spillovers as a free lunch for poorer nations. They should pursue a fair return for taxpayers while designing grant programs, visa rules, and partnership rules that maximize the spread of knowledge. The proper test is simple. If a rule makes it easier for a method published this month to shorten a trial next year—anywhere—keep it. If it slows that process, change it. By doing this, we can begin to reduce the eight-year wait.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acosta, M., et al. (2024). Effects of co-patenting across national boundaries on patent quality: An exploration in pharmaceuticals. Economics of Innovation and New Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2023.2167201.

CEPR VoxEU (2025). Hidden exposures in domestic supply chains: The spread of foreign trade risks. VoxEU.org, 3 December 2025.

EFPIA (2025). The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures 2025. European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations.

NAFSA (2025). International Student Economic Value Tool: 2024–2025 national analysis. NAFSA: Association of International Educators.

OECD (2024). Main Science and Technology Indicators—Highlights, March 2024. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

OECD (2025). Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2025. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Open Doors (2025). International students in the United States, 2024/25. Institute of International Education.

WIPO (2024). World Intellectual Property Indicators 2024—Patents highlights. World Intellectual Property Organization.

Wouters, O. J., & Kuha, J. (2024). Low- and middle-income countries experienced delays accessing new essential medicines, 1982–2024. Health Affairs, 43(10), 1410–1419.

Freemind Group (2025). NIH secures ~$48B under CR through September 2025. Freemind Group Brief.

Coronado, D., et al. (2024). Disentangling the effect of international collaboration between inventors on patent quality. SSRN Working Paper.

Taikonauten (2025). Technological spillover effects: When innovation crosses boundaries. Insights.

Comment