Energy Efficient Housing Renovations and the Problem of Hot Housing Markets

Input

Modified

Thick markets discourage energy-efficient renovations Thin markets often push owners to upgrade Subsidies should depend on local market thickness

Energy-efficient housing renovations are meant to be the quiet workhorse of Europe’s climate and social policy. Yet one number shows how far reality lags behind ambition: 1%. That is roughly the share of the EU building stock that undergoes energy renovation each year, even though about 85% of buildings were built before 2000, and three-quarters of them have poor energy performance. Buildings consume around 40% of all energy used in the EU and about half of its gas; close to 80% of the energy used in homes goes to heating, cooling, and hot water. At the same time, around 40 million Europeans recently reported being unable to afford adequate heating. Energy-efficient housing renovations should sit at the centre of the triple challenge of emissions, bills, and comfort. Instead, the EU is trying to decarbonise a leaky, ageing building stock at a flow rate that would take a lifetime to make a visible dent. The question is not only how to fund more upgrades, but why owners in some places queue up for renovation programmes while owners in others cash out and sell unrenovated homes into hot markets.

Market thickness and the renovation puzzle

Energy policy often treats households as if they lived in one stylised national market. In reality, owners make decisions about energy-efficient housing renovations in local markets that differ starkly in how quickly homes sell and how often people move. Economists call this “market thickness”: a thick market has many buyers and sellers active at the same time, with fast turnover and short listing times; a thin market has few transactions and long waits. In a thick urban market, owners know that almost any apartment will sell. In a thin rural or small-town market, they worry that a tired, cold flat might never attract a buyer. Those expectations shape whether they see renovation as a necessary investment or an optional luxury. In other words, the same subsidy will pull very different behavioural levers in Vilnius, Riga, or a small eastern municipality.

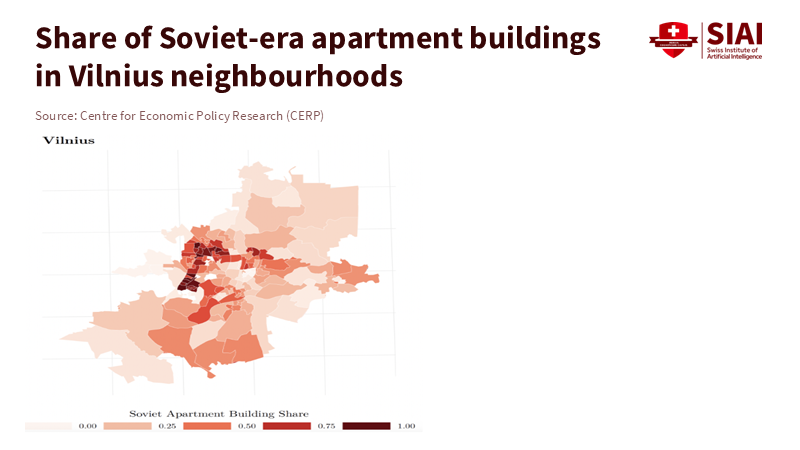

Recent Lithuanian evidence makes that puzzle tangible. Uniform Soviet-era apartment blocks still house about two-thirds of the population, and fewer than 15% of eligible blocks have been renovated despite almost two decades of preferential loans and grants covering up to 30% of project costs. Renovated flats do sell for more: tracking repeat sales of identical dwellings suggests an average price premium of around 8% after an energy-efficiency upgrade. Yet once owners deduct construction costs, even after subsidies, the typical net return on energy-efficient housing renovations is negative, on the order of a quarter of the money invested. Strikingly, those net returns look slightly less harmful in the three largest cities. Still, renovation activity is lower there than in smaller municipalities. In dense urban markets, owners anticipate a higher likelihood of moving due to job or family changes. They are also less confident that buyers will fully pay for the future energy savings embedded in the dwelling. It becomes rational to sell quickly and walk away from the insulation project.

This mechanism runs counter to the intuition that “thick markets solve problems.” In a thin market, an owner of one flat in a block of near-identical units faces a different calculus. A renovated apartment may stand out as one of the few warm, cheap-to-heat options in a town with little new construction. That distinctiveness matters more when there are very few buyers and each buyer looks carefully at running costs. Moreover, owners in thin markets often expect to stay longer, so they can enjoy more of the future savings on energy bills before selling. The upshot is that energy-efficient housing renovations can be privately more attractive in thin markets than in thick ones, even if headline price data suggest otherwise. If policy ignores that asymmetry, it risks deploying scarce subsidy budgets where they are least likely to change behaviour, and underfunding the places where owners are structurally biased towards selling unrenovated homes.

Energy-efficient housing renovations as a welfare policy

The stakes go beyond emissions targets and resale values. Energy-efficient housing renovations are a welfare policy for millions of households living in cold, draughty homes that they cannot afford to heat. Buildings account for about 30% of global final energy consumption and 26% of energy-related emissions, and existing technologies could already deliver significant reductions in both. In Europe, 85% of buildings were built before 2000, and 75% have poor energy performance; yet the annual renovation rate remains around 1%. The European Commission’s Renovation Wave aims to renovate 35 million buildings by 2030 and at least double the rate of energy renovations. At the same time, the Commission estimates that around 40 million people in 2022 could not afford to heat their homes properly. Energy-efficient housing renovations are thus central to lifting households out of energy poverty while meeting the new Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) target of a zero-emission building stock by mid-century.

Eastern Europe’s ageing blocs show both the urgency and the opportunity. In Latvia, officials estimate that there are about 38,000 apartment buildings nationwide, of which about 26,000 require renovation. The Ministry of Economics expects that by the end of next year, just under 6% will have been modernised. Local housing managers stress that international studies of similar serial blocks suggest that renovating a building to modern standards costs roughly one-third as much as constructing a new one from scratch. Renovation, therefore, preserves a valuable housing asset created by previous generations, extends its lifespan, and delivers warmer homes at a lower capital cost than wholesale rebuilding. Academic work on Latvia’s residential market reinforces the picture: Soviet-era multi-storey blocks dominate the housing stock, and the current pace of energy-efficient renovations is insufficient to meet national and EU energy efficiency objectives. In cold climates where heating accounts for most residential energy use, energy-efficient home renovations reduce both emissions and winter hardship. Yet even with grants and EU-backed loan programmes, uptake remains slow in many cities.

The welfare benefits of faster, energy-efficient housing renovations are not abstract. In EU homes, roughly 80% of energy use goes to heating, cooling, and hot water, and buildings consume around half of the bloc’s gas. In a world of volatile gas prices and geopolitical risk, every insulated wall and triple-glazed window is a form of insurance. More efficient homes reduce arrears for utilities, lower public spending on emergency bill support and health care for cold-related illnesses, and sharpen the impact of income transfers because less of each euro leaks out through inefficient boilers and uninsulated roofs. For ageing Soviet-era blocks that may stand for decades more, energy-efficient housing renovations also reduce the risk of sudden structural failures that force costly relocations. Latvia’s example shows that the economic case for renovation is clear on paper. The real challenge is to design policies that align that logic with the incentives facing owners in very different local housing markets.

Smarter subsidies for thick and thin housing markets

Current national programmes often rely on uniform subsidies, especially for owner-occupied apartment blocks. A scheme covers 30% of eligible renovation costs everywhere and provides similar technical assistance regardless of local conditions. The Lithuanian evidence suggests that this approach is, at best, blunt. Despite long-running programmes, fewer than 15% of eligible Soviet-era blocks have been renovated, and the average owner still faces a negative net financial return even after support. Moreover, the net returns are less harmful in large cities than in small municipalities. Still, renovation rates are lower in those same cities. That pattern is complex to reconcile with a story based only on credit constraints, information gaps, or coordination failures. It points instead to housing market structure: in thick markets, owners expect to move more frequently and do not believe they will recoup the full value of energy-efficient housing renovations when they sell. The equilibrium outcome is a steady flow of unrenovated, energy-hungry homes trading hands in hot markets.

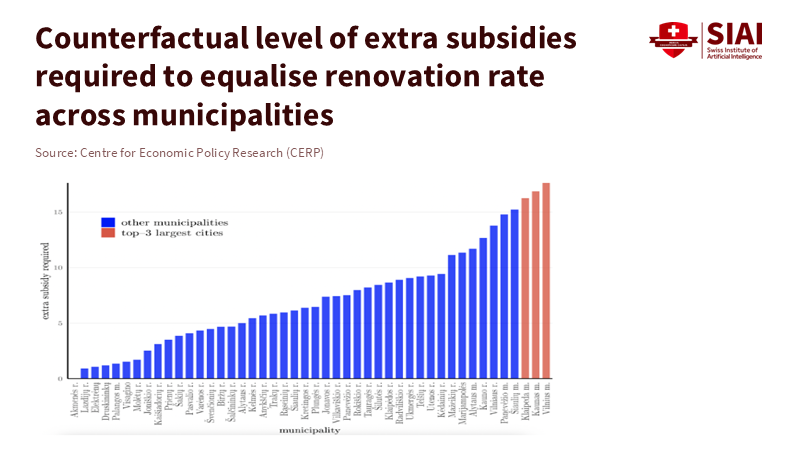

A more innovative design would start from a simple principle: the marginal euro of subsidy should go where it changes renovation behaviour the most. That does not mean abandoning support in thin markets. Owners there may still face severe liquidity constraints, and the poorest households often live in small towns or remote regions. But the Lithuanian calculations show that some rural municipalities would require only modest increases in subsidy rates to reach target renovation thresholds. At the same time, some thick urban markets would need much larger boosts, in some cases above 15 percentage points, to achieve comparable renovation rates. Instead of a flat national rate, governments could set a baseline subsidy for energy-efficient housing renovations and then apply a market-thickness adjustment. Municipalities with short average selling times, high turnover, and high price levels would receive larger top-ups per unit of energy saved. Those with fragile markets and already high renovation activity would receive smaller top-ups but more support for technical assistance and upfront project preparation, where coordination is the binding constraint.

Such a scheme would be easier to administer than it sounds. Most countries already collect detailed transaction data through land registries or tax authorities. From that data, they can calculate simple indicators such as median days on market and annual turnover per dwelling. These can be combined into a transparent “market thickness index” that guides the top-up level for energy-efficient housing renovations. In thick markets, governments could go further and attach energy performance conditions to the act of sale itself. For example, buyers of particularly inefficient flats in fast-moving urban areas could be offered time-limited, high-intensity support to complete energy-efficient housing renovations within a fixed window after purchase, with on-bill repayment mechanisms to smooth cash flow. In slow markets, where time-on-market is long and bargaining power is often with buyers, smaller subsidies may suffice if owners believe a renovated property will secure a sale. The key shift is to treat housing market structure as a central design variable, not as an afterthought.

From flat subsidies to clever market desig

Any move towards differentiated support will raise concerns about fairness and complexity. Urban taxpayers may ask why their cities receive higher per-unit subsidies for energy-efficient housing renovations, while rural residents may fear being left behind. Critics may argue that market-thickness metrics are technocratic and hard to explain. These concerns deserve a clear response. First, a market-adjusted system can preserve a universal baseline. Every qualifying building, regardless of location, receives a core level of support for energy-efficient housing renovations. The thickness-based component only affects the top-up. Second, the justification is not abstract: thick markets are precisely where owners are structurally tempted to sell unrenovated homes, even when the social value of renovation is high because of dense populations and strained energy systems. Targeting more generous grants, low-interest loans, and transaction-linked incentives to those markets is therefore a way to align private decisions with public goals, not a reward for already prosperous cities.

It is also essential to recognise that subsidy design is only one lever. Credit constraints, split incentives between landlords and tenants, a lack of trusted contractors, and administrative burdens all limit the implementation of energy-efficient housing renovations. Those barriers often bite hardest in thin markets, where incomes are lower and skills shortages acute. That is why a market-thickness approach should be paired with a broader toolkit: one-stop shops that bundle technical advice and financing; building-level governance reforms that make it easier for apartment owners’ associations to decide on renovations; and targeted social support for low-income households in both thick and thin markets. These instruments complement, rather than replace, the idea that subsidy intensity should vary with the underlying housing market structure.

The alternative is to continue with flat subsidies and hope that the 1% renovation rate somehow accelerates to meet the Renovation Wave’s promise of 35 million upgraded buildings by 2030. That hope looks thin. Buildings already account for over a third of global energy consumption and emissions, and the sector's energy intensity needs to fall far faster in this decade than it has in the last. In Latvia, most of the 26,000 apartment buildings earmarked for renovation will still be leaking heat unless programmes become both larger and more sharply targeted. In Lithuania, large shares of Soviet-era blocks will continue to change hands without ever seeing deep upgrades if owners in thick markets can always find a buyer for an inefficient flat. Energy-efficient housing renovations are too central to climate goals, energy security, and basic household welfare to be left to uniform, one-size-fits-all subsidies. Policy should match money to market structure. If it does, renovation will stop being a slow, marginal activity and start to reshape the housing stock at the speed that both the climate and Europe’s cold homes demand.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

European Commission (2024a). Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. EU Energy Efficiency portal.

European Commission (2024b). Renovation Wave. EU Energy Efficiency portal.

International Energy Agency (2023). Buildings. IEA online resource.

Jakucionyte, E., & Singh, S. (2025). The effects of energy efficiency renovation of residential buildings on the housing market: A study from Lithuania. Bank of Lithuania Working Paper No. 135.

Latvian Public Media (LSM) (2025). Study: Soviet-era buildings in Latvia can still live long if renovated. LSM.lv English, 21 January 2025.

Welikala, D. H. N. (2025). Energy Efficiency Trend in the Latvian Residential Property Market. Baltic Journal of Real Estate Economics and Construction Management.

Comment