Why Ensemble Monetary Policy Should Replace Single-Model Dogma

Input

Modified

Central banks leaned on single models and badly misread the inflation surge Ensemble monetary policy blends many models to create safer, more robust rate rules Teaching and adopting ensemble monetary policy can rebuild trust through cautious, transparent decisions

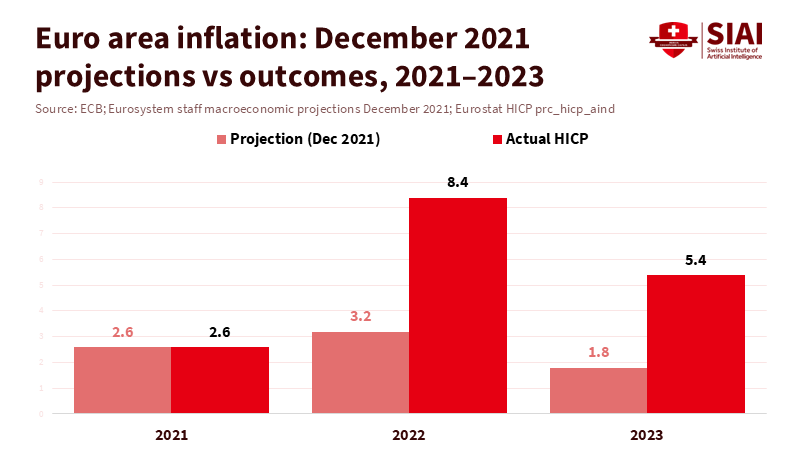

In late 2022, inflation in the euro area was almost eight percentage points higher than the central bank had predicted a year earlier. This mistake caused real incomes to fall much faster than expected. Governments, businesses, and families all rushed to adjust wages, contracts, and debt plans on short notice. Later analysis revealed that incorrect assumptions about energy prices and other shocks accounted for about three-quarters of the early forecast errors, not just random fluctuations. Globally, inflation peaked at around 8.8% in 2022, and the IMF now predicts it will decrease to about 4-5% by 2025. However, the impacts of that forecasting failure are lingering. The core issue was not just a bad quarter or one poor judgment. It was a deep reliance on a single “true” model of the economy, when no such model actually exists. Ensemble monetary policy aims to close this gap by shifting from a single-model approach to a systematic diversification of models, similar to the ensembles that dominate modern machine learning.

Ensemble monetary policy and the end of the perfect model

The idea behind ensemble monetary policy is straightforward. Central banks do not know which economic model is correct, and recent events have made this undeniable. Forecasts from major central banks and international organizations consistently underestimated the inflation surge after 2021, even for short time frames. In the euro area, studies show that the discrepancy between projected and actual inflation at the end of 2022 was close to eight percentage points. Simultaneously, ECB research indicates that its inflation projections are useful for time horizons of about 1 year. Still, their reliability diminishes almost to zero for forecasts spanning 4 to 8 quarters. In other words, central banks heavily invested in medium-term predictions that were barely more useful than a simple “target plus noise” rule, while treating model uncertainty as a minor concern. Ensemble monetary policy changes this hierarchy.

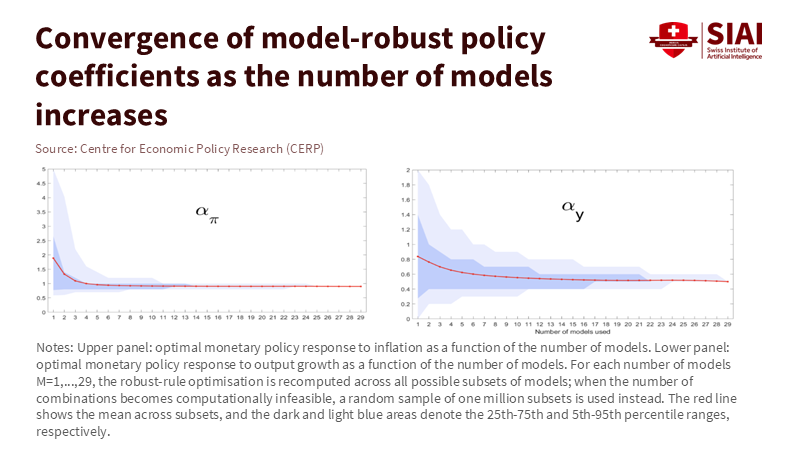

Ensemble monetary policy starts with the belief that model uncertainty is the primary design constraint, not an afterthought. Instead of refining a preferred dynamic model, policymakers examine how a simple rule—such as a Taylor-type rule linking the policy rate to inflation and output growth—performs across a range of plausible models. Recent research evaluates such rules using a set of 29 structural models from a significant macroeconomic model database, spanning different frictions, expectation-formation mechanisms, and calibration methods. When the rule is selected to minimize average losses across all 29 models, a clear pattern emerges. The ensemble rule suggests more cautious adjustments to interest rates than the single-model optima. Yet, it performs similarly across models and provides stable recommendations when enough models are included. The cost of robustness—measured as the loss compared to each model’s specific optimum—remains well below the traditional thresholds that central banks accept when fine-tuning rules. Robustness across models, rather than precision within one model, becomes the guiding principle of ensemble monetary policy.

A parallel from machine learning makes the logic of ensemble monetary policy more straightforward to understand. A single decision tree classifier is easy to follow but sensitive; minor changes in data can alter its forecast. In contrast, ensembles like random forests combine many trees and typically yield lower prediction errors in practice because averaging reduces variance and reduces the risk of overfitting. Systematic comparisons across areas such as biomedical classification indicate that tree-based ensembles outperform individual models across a range of problems. Recent findings in the Journal of Machine Learning Research go further, showing that random forests can lower both bias and variance compared to straightforward bagging methods. In the field of education research, a 2025 study on student performance prediction shows an R² of around 0.93 for a carefully tuned ensemble, significantly outperforming both individual models and typical ensembles. Ensemble monetary policy applies this insight to macroeconomic decision-making. No single structural model captures the entire economy, just as no single tree can capture a complex data-generating process. Therefore, the safest way to set interest rates is to consider multiple models simultaneously and allow their errors to offset one another.

What ensemble monetary policy looks like in practice

For an ensemble monetary policy to go beyond just a catchy idea, it needs a straightforward institutional setup. The first step is to formalize the model set. Instead of relying on a single core DSGE model and a few scenario tools, central banks would develop a dynamic library of structural and semi-structural models that capture different views on wage and price rigidity, expectation formation, fiscal feedback, and financial frictions. Each model would have to pass basic empirical tests and replicate key data features—such as the average responses of inflation and output to past policy moves—but no framework would be treated as the sole benchmark. Within that library, ensemble monetary policy would establish a simple rule and evaluate its performance across all models, assigning each model an equal or clearly defined weight. The aim is not to find the rule that appears optimal in one model, but to identify the rule that avoids severe issues across all models.

Evidence from recent multi-model exercises suggests this is a viable way to guide policy. When straightforward interest-rate rules are optimized for performance across many structural models, the loss in any individual model relative to its tailored optimum typically remains well below the loss that central banks consider “acceptable” when they calibrate rules within a single framework. Additionally, ensemble-based rules promote more cautious reactions to shocks. As more models are included in the set, the suggested responses to inflation and output growth tend to converge toward moderate values, and the variance among model subsets shrinks. Policy becomes less aggressive but also more stable and predictable. This is the essence of ensemble monetary policy: accept a slight loss of model-specific optimality in exchange for a significant gain in robustness, especially when the nature of shocks is difficult to pinpoint in real time.

Communication is the second practical aspect of ensemble monetary policy. The multi-model approach aligns well with probability ranges rather than single-point forecasts. Careful assessments of euro-area projections indicate that inflation forecasts contain genuine information for time horizons of about 1 year, but their predictive value quickly declines thereafter. The honest message to the public and to students learning about monetary policy is that, beyond a year, inflation is better described as a distribution than as a precise figure. Under ensemble monetary policy, central banks would present fan charts and scenario bands that clearly show the range of outcomes across their model set. They would emphasize the parts of that range that matter for decisions—for instance, the likelihood that inflation will stay above target even if energy prices stabilize—rather than focusing solely on the exact median point forecast. This method makes uncertainty a central part of communication instead of a mere footnote. It aligns public expectations with the idea that the policy is inherently robust.

Teaching ensemble monetary policy to the next generation

For ensemble monetary policy to influence real decisions, it must change how we teach macroeconomics and policy. Graduate monetary courses still focus on a small number of canonical models, presented one by one, each with its own calibration and “optimal” rule. Students learn to solve and simulate those models, but seldom consider how policy advice shifts when several models are analyzed together. Courses and textbooks often reinforce the search for a single best framework, even as real-world policy debates reveal significant disagreements about the appropriate model for each situation. An education system built around this search risks producing new economists who will repeat the same errors that caused the recent inflation surprise.

A practical way forward is to integrate model diversification directly into standard assignments. Instead of asking students to derive an optimal policy within a single model and report a single set of coefficients, instructors can provide a small portfolio of models based on different assumptions about expectations, wage rigidities, or credit frictions. Students would first calibrate or estimate each model using the same data, then calculate simple rules and observe how the suggested interest-rate paths diverge. The final step would involve constructing ensemble monetary policy rules—such as averaging or minimax combinations of those coefficients—and comparing performance across models. This exercise is straightforward, but it encourages students to face model uncertainty as a fundamental reality rather than just a theoretical concern. It also reflects trends in educational analytics, where ensemble methods already support high-performing systems for predicting student outcomes.

Professional training programs for central bank staff can adopt the same framework. Multi-week courses for new economists could dedicate as much time to comparing models and designing ensembles as to mastering the institution’s primary projection model. Internal dashboards could show, for each meeting, how a specific interest-rate rule performs across the model library and how the ensemble monetary policy rule compares to single-model recommendations. Crisis simulation workshops could challenge participants to explain how an ensemble rule would respond to a new supply shock or financial disturbance under different structural assumptions, rather than debating which single model best describes the situation. Outreach to journalists, parliamentarians, and the general public could emphasize that differences among models—and among staff—are not a weakness but a source of stability within the ensemble monetary policy framework. Diversity of views becomes an asset, not something to suppress.

Ensemble monetary policy as a policy imperative

The recent rise in inflation has served as a harsh lesson in what occurs when institutions overestimate the accuracy of their forecasts. Global inflation is now declining, with IMF projections indicating headline inflation will drop to about 5.8% in 2024 and 4.4% in 2025, as tighter monetary policy and easing supply pressures begin to take effect. However, this episode has shown how quickly trust can diminish when projection errors are significant and occur repeatedly. Detailed reviews of forecasting performance indicate that even well-funded institutions struggled to tell temporary shocks from persistent ones in real time, and forecast accuracy declines sharply as the time frame extends beyond a year. In response, some central banks have shifted to “meeting-by-meeting” guidance and placed a greater emphasis on incoming data. This move toward discretion may prevent the embarrassment of clear forecast errors. Still, it risks creating a new issue: a policy that seems reactive, unstable, and hard to explain. Ensemble monetary policy provides a means to remain rule-based while acknowledging uncertainty.

The case for ensemble monetary policy brings us back to that eight-percentage-point forecasting error in 2022. A single-model perspective viewed the inflation spike as mostly temporary and supply-driven, leading to a sluggish policy response and narrow communication about risks. An ensemble framework might not have guaranteed a perfect prediction. Still, it would have compelled policymakers to consider a broader range of possible dynamics, including more persistent demand-side pressures. It would also have encouraged them to communicate forecast ranges and tail risks more transparently. For educators, the message is clear: courses that still present monetary policy as applying one preferred model to an uncertain world are teaching outdated practices. For central banks and finance ministries, the goal is to integrate ensemble monetary policy into their rules, model governance, and public communications. No framework can eliminate uncertainty, but some can manage it better than others. Ensemble monetary policy may not be a quick fix. Still, it offers the best protection against the next major forecasting miss—and that makes it essential, not optional.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Chahad, M. et al. (2022), “What explains recent errors in the inflation projections of Eurosystem and ECB staff?”, ECB Economic Bulletin, 2022(3), 49–57.

Chahad, M. et al. (2023), “An updated assessment of short-term inflation projections by Eurosystem and ECB staff”, ECB Economic Bulletin, 2023(1), 61–65.

Conrad, C. and Z. Enders (2024), “The ECB’s projections and their limits”, SUERF Policy Brief, No. 945.

Dück, A. and F. Verona (2025), “Robust monetary policy rules across models and frequencies”, working paper, Bank of Finland and zeb consulting.

European Central Bank (2025), “The 2021–24 inflation surge through the lens of the ECB-BASE model”, ECB Economic Bulletin, 2025(3), Focus Article.

Husayn, M., O.R. Adegboye and A. Alzubi (2025), “GWO-Optimized Ensemble Learning for Interpretable and Accurate Prediction of Student Academic Performance in Smart Learning Environments”, Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12163.

International Monetary Fund (2023), World Economic Outlook Update, January 2023: Inflation Peaking amid Low Growth, Washington, DC.

International Monetary Fund (2024a), World Economic Outlook Update, January 2024: Policy Pivot, Prospects and Risks, Washington, DC.

International Monetary Fund (2024b), “As inflation recedes, global economy needs policy triple pivot”, IMF Blog, 22 October.

Lee, S. et al. (2020), “Comparing performance of ensemble methods in biomedical data classification”, PLOS ONE, 15(6), e0233484.

Liu, B. and R. Mazumder (2025), “Randomization Can Reduce Both Bias and Variance”, Journal of Machine Learning Research, 26, 1–46.

Comment