Climate risk insurance and Europe’s sovereign safety net

Input

Modified

Climate disasters intensify as Europe stays weak Rising losses shift from insurers to states Europe must build resilient climate insurance

Only a quarter of climate-related disaster losses in the EU are insured. The rest falls on households, businesses, and governments. Average weather-related losses have reached about €44.5 billion each year between 2020 and 2023, which is more than double the average for the previous decade. At the same time, euro area insurers hold nearly a fifth of outstanding government bonds, playing a crucial role in the region’s financial safety net. Here, climate risk insurance faces challenges from Europe’s low growth and strained public finances. Years of low interest rates have cut into insurers’ profit margins. The energy crisis from Russia’s war in Ukraine reduced household incomes and pushed governments to borrow more. Climate losses are now increasing faster than the tax revenue that supports both insurers and governments. This creates not only an insurance issue but also a legal one. It is a slow-building systemic risk connecting climate risk insurance, insurers' finances, and the fiscal capacity of European governments.

Climate risk insurance under strain in a weaker Europe

For much of the past decade, European insurers operated in an environment of ultra-low interest rates and slow growth. Life insurers provided long-term guarantees while investing premiums in sovereign and corporate bonds that often yielded little to no real return. Profit margins decreased, even though balance sheets appeared stable. Solvency data show how tight the margins became: European regulators reported a median net combined ratio for non-life business rising to about 98% in mid-2023, close to the break-even point. Meanwhile, life insurers reported a median investment return of about –22% in 2022 due to unrealized losses on bond portfolios when interest rates rose. In a stagnant economy, there was little ability to pass on higher costs to customers without losing business. Climate risk insurance was already operating on thin ice.

The broader economic situation made that ice thinner. The EU avoided a formal recession after the pandemic. Still, medium-term growth remains modest, and the war in Ukraine caused a historic energy shock. One estimate indicates that European households spent approximately €673 more on energy and €1,316 more on food due to the crisis, despite support packages totaling around 4% of GDP, further straining public budgets. In this scenario, climate risk insurance has to address more frequent and costly events while competing with other pressing spending needs for families and governments. When budgets are tight, insurance is often one of the first items cut, especially when the risks seem remote. This reduces the pool of premiums intended to cover future claims and weakens a sector crucial for handling climate shocks.

At the same time, the risk aspect of the climate risk insurance equation has not stood still. Global insured losses from natural disasters have surpassed $100 billion for four consecutive years, reaching around $108 billion in 2023, driven by more frequent severe storms, floods, and wildfires. Europe is not immune to this trend: regulators report that weather-related disasters in the EU caused average annual losses of €44.5 billion from 2020 to 2023, with climate change and urbanization as key factors. Yet only about 25% of those losses are insured, leaving a significant protection gap that increases vulnerability. This gap means that each new flood or wildfire affects a shrinking base of climate risk insurance policies while expanding the number of uninsured victims who rely on the state. Insurers face higher claims on the policies they do write, while governments are expected to cover the rest.

How climate risk insurance feeds into sovereign debt risk

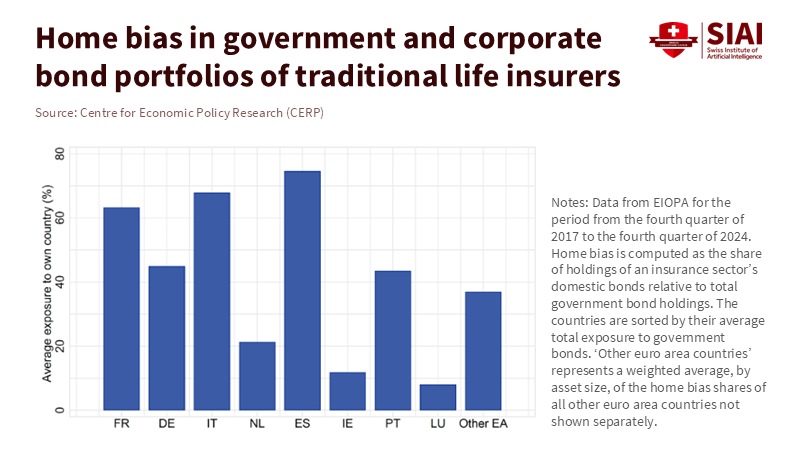

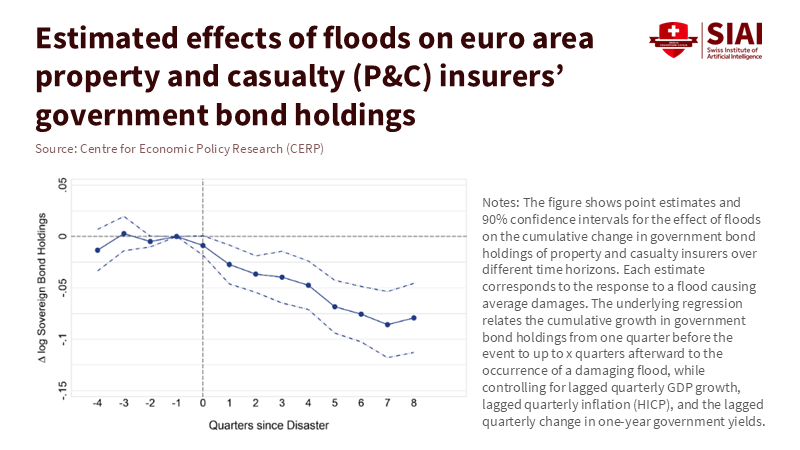

Euro area insurers are not only buffers against climate shocks; they are also significant holders of sovereign debt. Recent research has shown that, on average, euro area insurance companies own about 18% of each government bond at the start of the sample period, making them the second-largest domestic creditors after banks. Traditional life insurance products have often offered returns linked to yields on domestic sovereign bonds, leading firms to maintain a strong home bias in their portfolios. Climate risk insurance is directly related to the funding costs for European states. When large-scale disasters occur, insurers may need to sell liquid assets, such as government bonds, to meet claims or rebuild capital. Suppose those bonds are already under strain due to higher state spending on reconstruction or energy subsidies. In that case, a feedback loop can form between climate shocks, insurers, and sovereign bond yields.

The widening climate insurance protection gap adds another layer to this situation. With only a quarter of climate-related disaster losses insured in the EU, the remaining three-quarters fall on households, businesses, and the public sector. Regulators warn that annual losses from floods, storms, and droughts have more than doubled since the previous decade and that Europe is increasingly unable to cope with the costs. When climate risk insurance is too narrow or too costly, governments may feel pressured to act as the insurer of last resort. They will rebuild homes and infrastructure, support affected businesses, and protect banks whose collateral has lost value. Each intervention increases public debt, which is partly held by the very insurers whose business models are weakened by the same events. Thus, the climate risk insurance gap evolves into a fiscal risk and, consequently, a financial stability risk.

This is why several commentators now warn that climate risk insurance could trigger a “climate-induced credit crunch.” Senior leaders from major European insurers have cautioned that if rising losses make large areas of property and infrastructure effectively uninsurable, essential financial contracts like mortgages may fail in those regions. Without reliable climate risk insurance, banks cannot safely lend against homes in flood-prone areas or fire-risk zones. Municipalities struggle to issue long-term bonds for assets that may not endure their intended lifespan. In Europe’s already-slow economies, where both public and private balance sheets carry legacy debts from the financial crisis, the pandemic, and the energy crisis, the impact of climate change could push vulnerable regions over the edge. The relationship between climate risk insurance and sovereign debt is no longer a mere academic concern. It is evolving into a clear channel through which climate change can alter Europe’s financial landscape.

Repricing climate risk insurance, not abandoning insurers

The narrative is not solely one of decline for insurers. Recent years have also shown what seems like a revival. For instance, Lloyd’s of London reported an underwriting profit of £5.9 billion in 2023, with a combined ratio of about 84%, marking its best performance in years. Major European reinsurers posted record-low loss ratios in 2024 as higher premiums and a relatively mild year for large disasters boosted earnings. From this perspective, climate risk insurance has entered a new, pricier phase in which prices better reflect the increasing hazards. Stock prices and returns on equity have bounced back from the low-rate era slump. For investors focused on headline profits, the sector may appear more resilient than the troubling climate news suggests.

The hazard is that this initial repricing phase is misinterpreted as a complete adjustment. Global insured disaster losses remain above $100 billion annually and are trending upward; analysts at a prominent reinsurer estimate they could double over the next decade as temperatures rise. Regulators highlight that the frequency of “medium-severity” events, such as convective storms and urban flooding, is increasing faster than that of traditional catastrophic incidents, particularly in Europe. Climate models predict that under current policies, the world is on track for about 3.1°C of warming this century, exposing larger areas of Europe to ongoing risks of drought, heat, and flooding. Therefore, climate risk insurance is being repriced amidst changing conditions. Current premiums that seem high now may still be underestimating future losses.

At the same time, many significant climate risks do not clearly appear in insurers’ financial statements. Businesses in vulnerable regions are facing steep premium hikes, higher deductibles, or outright denial of coverage for climate-related natural disaster risks. Some insurers are completely withdrawing from the specific areas or lines of business rather than continue to provide climate risk insurance at a loss. Financial advocacy groups document that Europe’s overall insurance coverage is declining, leaving a greater share of climate losses to taxpayers and smaller mutual schemes. This trend does not show up in any single combined ratio or solvency figure. However, it alters the sector's dynamics. A smaller, more selective climate risk insurance market can be profitable for the firms that remain involved. It can also become socially and financially fragile if too many risks are pushed onto the public sector.

A policy agenda for resilient climate risk insurance

The crucial question now is not whether climate risk insurance should exist, but how to keep it both sustainable and affordable amid frequent shocks and slow growth. European regulators are starting to propose solutions. The EU’s insurance authority has raised capital requirements for natural disaster risk and created national-level dashboards to monitor the climate insurance protection gap. The ECB and EIOPA have proposed an EU-wide public-private reinsurance model for climate disasters, funded by risk-based premiums, with an additional European fund to support rebuilding public infrastructure after disasters. The goal is to ensure that climate risk insurance can continue to function even in areas repeatedly affected by severe events, while also maintaining the motivation for risk reduction. Without such support, private insurers may continue to pull back, forcing the government to improvise assistance in each crisis.

A second necessary component of an effective agenda is incorporating climate risk insurance into the assessment and management of sovereign risk. Research on euro area bond markets shows that home-biased holdings by insurers can increase sovereign stress, especially when local bonds are seen as risk-free in capital regulations. As climate disasters drive up public expenses and volatility in regional economies, this assumption becomes harder to sustain. Climate stress tests for insurers and banks already connect physical risk to credit losses theoretically; these tests need to lead to specific limits on concentrated exposures to governments that are vulnerable both financially and climatically. Climate risk insurance and sovereign debt management should be regarded as part of the same stability toolkit, rather than as separate technical areas.

Finally, educators and administrators have a role to play. Universities, business schools, and training institutions shape how future actuaries, risk managers, and policymakers perceive climate risk insurance. Curricula that view climate shocks as remote events or overlook the connection between insurance coverage and public finances risk preparing professionals for an outdated world. Courses in finance, public policy, and economics should include case studies on the European climate insurance protection gap, sovereign risk feedback loops, and the design of public-private schemes. Administrators in education systems, managing large physical estates and pension funds, can adopt a similar perspective in their own decisions: how to ensure affordable climate risk insurance for campuses and how to assess investment in insurers that are, or are not, adapting their business models.

The alternative is to slide toward a patchwork of climate risk insurance in wealthier areas and informal self-insurance in poorer regions. Europe is already witnessing hints of this, with coverage rates below 5% in some Member States and rising concerns among regulators that citizens "cannot cope" with the costs of extreme weather. If left unchecked, this trend will increase inequality, diminish confidence in public institutions, and raise the risk of a climate-driven credit crunch. A different path is still possible. It treats climate risk insurance as vital economic infrastructure, aligns regulatory rules with climate realities, and uses public support to maintain broad coverage while encouraging risk reduction. For educators, administrators, and policymakers, the choice is clear: build this system now, or face the reality that the next generation will inherit a hotter continent and a weaker, more vulnerable financial safety net.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Allianz Research (2024). Two years of war in Ukraine – impacts on Russia and Europe. Allianz Group.

Bank for International Settlements & International Association of Insurance Supervisors (2025). Mind the climate-related protection gap: Reinsurance pricing and underwriting considerations. FSI Insights on Policy Implementation No. 65.

Boermans, M. et al. (2025). Quantitative easing and preferred-habitat investors in the euro-area sovereign bond market. De Nederlandsche Bank Working Paper No. 826.

European Central Bank (2023). EIOPA and ECB call for increased uptake of climate catastrophe insurance. ECB.

European Central Bank (2024). The climate insurance protection gap. ECB.

European Central Bank & European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2024). Towards a European system for natural catastrophe risk management. ECB–EIOPA Joint Paper.

European Commission (2023). European Economic Forecast – Spring 2023. Institutional Paper.

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2023). Insurance Risk Dashboard – November 2023. EIOPA.

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2024). Insurance natural catastrophe protection gaps – a multidimensional approach. EIOPA.

Finance Watch (2025). Breaking the spiral of uninsurable climate losses. Finance Watch.

Financial Times (2025). “Europe ‘can’t cope’ with extreme weather costs, warns insurance watchdog.” Financial Times, 3 February.

Fitch Ratings (2024). “Fitch predicts highest net combined ratio for German non-life.” Fitch Ratings / Reinsurance News.

Insurance Business (2025). “Europe’s top four reinsurers see peak P&C profits amid benign losses – Fitch.” Insurance Business.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (2023). Global Insurance Market Report 2023. IAIS.

International Energy Agency (2024). Russia’s war on Ukraine. IEA.

Lloyd’s of London (2024). “Lloyd’s of London doubles underwriting profit.” Reported in The Times.

Loughborough University (2025). “Climate change is becoming an insurance crisis.” Comments and Analysis.

Munich Re (2023). Natural disaster figures 2023. Munich Re.

Munich Re (2025). Natural disaster figures 2024. Munich Re.

Reuters (2024). “ECB proposes EU scheme to expand climate insurance uptake.” Reuters.

Reuters (2025). “Climate change shows ‘claws’ with rising costs for disasters, Munich Re says.” Reuters.

Swiss Re Institute (2023). “Natural catastrophe insured losses continue to exceed $100 bln, Swiss Re Institute says.” Swiss Re Institute.

The Guardian (2025). “Climate crisis on track to destroy capitalism, warns top insurer.” The Guardian.

Comment