Teaching the Factory: U.S. Semiconductor Workforce Training After the Hyundai Raid

Input

Modified

The US funds fabs but lacks skilled workers Asian firms plug gaps with temporary foreign technicians Real fix: serious US semiconductor workforce training

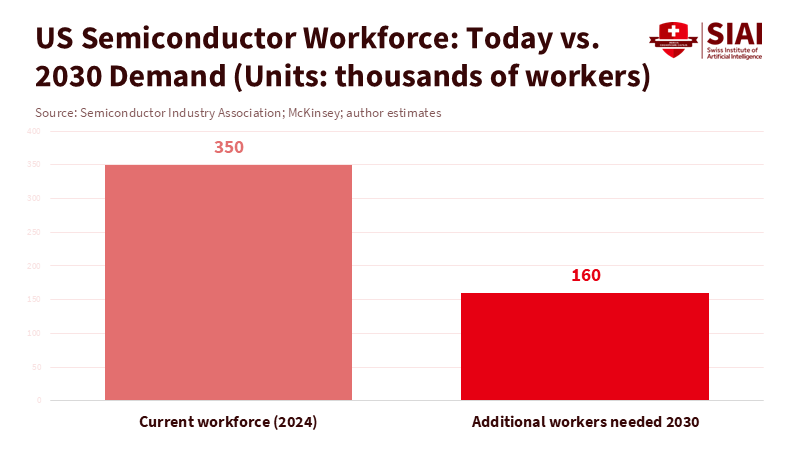

The fight for factory jobs in the United States has become a struggle over who teaches whom. The country has invested over US$200 billion in semiconductor plants, research, and tax credits. However, by 2030, it is projected to be short more than 150,000 skilled workers for chip-related roles. The current industry employs around 338,000 people, which is a modest starting point for such ambitious growth. New fabs are under construction, but many cannot progress from concrete to production without a large number of technicians who are simply not available. The immigration raid at Hyundai’s battery plant in Georgia in September 2025, in which about 475 workers were detained in a single morning, highlighted this gap. Many of those arrested were South Korean specialists brought in on short-term visas through subcontractors. They were not just a side note—they represented the missing training system. At the same time, the United States claims it wants “good jobs at home.” Still, its labor and visa rules push Asian multinationals to seek workarounds that appear illegal and unstable. U.S. semiconductor workforce training directly contributes to this contradiction.

U.S. Semiconductor Workforce Training as the Missing Link

The issue is not a lack of funding or words. The CHIPS and Science Act alone authorizes about US$280 billion in spending, including over US$50 billion specifically for semiconductor manufacturing, research, and workforce projects, along with generous tax credits for equipment and construction. Federal grants to large companies now total tens of billions of dollars, with major deals for chip plants in Arizona, New York, Texas, and Idaho. A commonly referenced analysis estimates that the program will create roughly 93,000 construction jobs and 43,000 permanent semiconductor jobs, at an average public cost of about US$185,000 per job each year over the life of the incentives. These are significant amounts for a sector that still employs fewer than 400,000 people total. Yet, key projects face delays because they cannot find enough people with the right skills to install, run, and maintain modern production lines.

This gap has been growing for decades. The share of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. has dropped from about one in six in 1990 to roughly one in twelve today, even as output has increased due to automation and offshoring. Large companies moved much of their high-volume production to Asia, while keeping design, branding, and finance jobs at home. Schools, parents, and local leaders urged young people to pursue four-year degrees and white-collar work. Community colleges and vocational schools, once the backbone of regional training, faced tight budgets and inconsistent support. In this environment, an advanced clean-room job in a suburban industrial park does not seem like a straightforward and respected career path. The U.S. semiconductor workforce training struggles because society no longer views hands-on industrial work as a first-choice career. Asian multinationals entering America notice thin talent pipelines, scattered centers of excellence, and very few options for plugging a new plant into a ready pool of technicians.

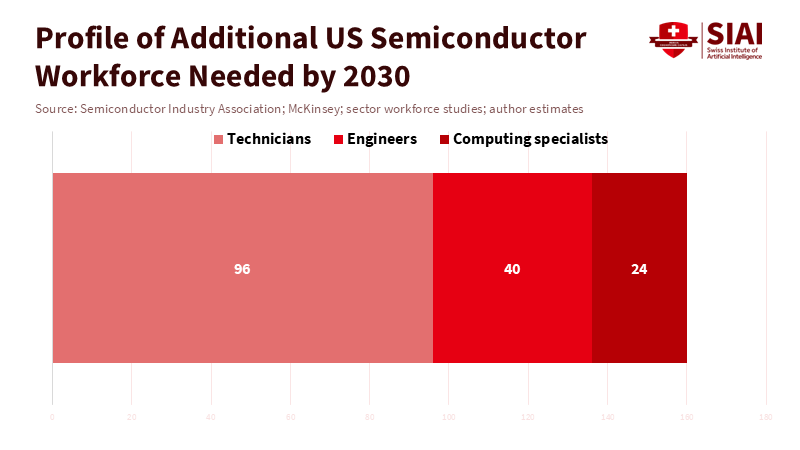

Two numbers illustrate the scale of the challenge. The Semiconductor Industry Association and related studies estimate current U.S. semiconductor employment at around 300,000. Workforce analyses by consulting firms and regional groups predict the need for more than 160,000 additional chip workers by 2030, including technicians, engineers, and computing specialists. Even with optimistic scenarios, a significant portion of those roles is at risk of remaining unfilled if current trends continue. The shortage is not just at the PhD level. Much of the projected gap lies in mid-skill technician jobs: people who can interpret sensor data, maintain lithography tools, calibrate robotic arms, and ensure production stability during long shifts. U.S. semiconductor workforce training must rebuild this middle layer, or the entire reshoring effort will be unstable.

Why Asian Manufacturers Lean on Visa Workarounds

The Hyundai raid in Georgia starkly revealed how Asian multinationals have been trying to fill the training void. Federal agents and state officers swept through Hyundai’s electric vehicle and battery complex early one morning, detaining around 475 workers. Investigative reports detailed networks of Korean subcontractors bringing in skilled workers on short-term visas or visa waivers to install equipment and prepare the plant. Many of these workers were not casual laborers—they were seasoned technicians and engineers who had worked on similar projects in Korea and other countries, moving from site to site as specialist teams. Local economic officials in Georgia admitted, after the shock of the raid, that these South Korean workers were the only ones who knew how to install and tune parts of the system, and that without them, the project would fall months behind schedule.

From the perspective of Korean companies, the logic is straightforward. When a firm builds a US$4–7 billion facility under strict deadlines, it cannot wait for a new wave of local workers to come from training programs that do not yet exist. It sends trusted workers, often in three-month rotations, and expects them to train local staff as they go. This practice is common not only in Georgia but also at various Asian multinationals in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe, sometimes with the approval of host governments. The difference in the United States is the combination of strict immigration laws, strong formal labor protections, and unpredictable enforcement priorities. When political sentiment shifts towards “illegal workers,” the workaround that kept a project on track is recast as a criminal operation. U.S. semiconductor workforce training is absent, so imported trainers step in. Then, enforcement agencies arrive, treating these imported trainers as the main issue.

The outcome is a fragile triangle of expectations. U.S. policymakers want jobs and factories, but they haven’t rebuilt the training system that once supported large industrial projects. Asian companies seek reliable rules but encounter a confusing mix of visa categories that do not align with their standard project team deployment. Local communities desire higher wages and visible job opportunities. Still, they mostly see foreign crews behind the fences of massive facilities. U.S. semiconductor workforce training should serve as a bridge between these interests. Instead, firms resort to B-1 business visas, short-term visitor waivers, and layers of contracting that obscure legal responsibilities. When a raid occurs, everyone claims surprise. The deeper issue is that training has become an afterthought. At the same time, the visa policy serves as a temporary fix to address domestic capacity constraints.

From Raids and “Illegal Labor” to a Training Compact with Taiwan

The emerging U.S. strategy toward Taiwan aims to move beyond improvised visa solutions. Negotiators are working on a plan in which Taiwanese chipmakers, led by TSMC, would increase investment in U.S. fabs and help train the domestic workforce at scale. Media reports often frame Washington’s demands as “hundreds of billions plus training”—capital commitments linked to formal skills transfer and support for curriculum development. This reflects a genuine shift. Rather than quietly relying on makeshift visa workarounds, the United States seeks to incorporate U.S. semiconductor workforce training into trade and investment agreements. Trainers would still come from Taiwan, but with clear categories and explicit goals for how many American technicians, engineers, and operators they can help train in a defined timeframe.

This is not an easy fix. Taiwan faces its own shortage of chip talent. Korean, Japanese, and European companies do too. Global estimates indicate that the industry will need hundreds of thousands more skilled workers across major hubs by 2030. Taiwanese firms cannot indefinitely send trainers abroad without weakening their talent pool at home. That is why the most realistic version of a training agreement sees foreign trainers as a catalyst rather than a permanent solution. U.S. semiconductor workforce training would combine short, focused on-site instruction by Taiwanese or Korean experts with longer, structured pathways in American schools and colleges. Community colleges, state universities, and union-run training centers would align their curricula with actual process flows inside fabs, not just generic “advanced manufacturing” content. Public funds would cover not only facilities and tax credits, but also labs, equipment, instructor salaries, and paid student apprenticeships.

For this compact to work, it needs to be detailed in the agreements. Subsidy contracts and trade deals should specify clear training metrics: how many apprentices must complete programs, how many local instructors need to be hired and trained, and how many workers must transition from trainee to permanent technician roles within a set timeframe. Visa regulations must create a specific category for foreign trainers, with defined duration and reporting requirements that everyone can monitor and plan around. Suppose a plant brings in a certain number of trainers. In that case, it should also commit to hiring a multiple of certified local staff by the time those trainers leave. Essentially, the U.S. semiconductor workforce training should be an integral part of industrial policy, not just a vague commitment. This approach is more demanding than the previous pattern of short tourist visas and informal overtime. Still, it offers greater stability for both companies and workers.

Designing Workforce Training That Can Survive Trump’s Second Term

The political climate makes this even more critical. A second Trump administration will emphasize reshoring, using groundbreaking ceremonies, ribbon-cuttings, and subsidy announcements to signal that “factories are coming home.” At the same time, campaign speeches and enforcement actions have heightened the focus on “illegal labor,” especially at high-profile sites like Hyundai’s Georgia plant. This combination poses obvious risks for Asian multinationals that rely on stable regulations. Suppose raids become a regular aspect of industrial policy. In that case, investors will view U.S. projects as politically risky, regardless of the incentives. Conversely, if enforcement is matched with a straightforward, reliable training and visa framework, it could encourage companies to move away from gray areas and build long-term partnerships with local institutions. U.S. semiconductor workforce training can serve as the anchor that transforms volatility into stability.

For educators, this means prioritizing chip-related programs as a core mission rather than a passing trend. High schools must provide clear pathways into technical roles and communicate them early and consistently. Community colleges should expand their programs in electronics, process control, mechatronics, and industrial IT, ensuring strong connections to specific employers. Universities can help by offering applied engineering programs linked directly to fab operations, not just to research labs. Teaching loads and budgets should allow instructors to stay current with industry tools, visit plants, and integrate new processes into their courses. U.S. semiconductor workforce training cannot depend on outdated textbooks and second-hand knowledge. The learning environment must strive to reflect the speed and accuracy of real production as closely as possible.

For administrators and policymakers, the focus should be on the institution. Funding formulas ought to reward the completion of high-quality technical programs, not just enrollment numbers. Apprenticeships need to be structured, compensated, and acknowledged, allowing students who spend three years alternating between classrooms and clean rooms to earn credentials that are valuable across employers. Support services—such as transportation, childcare, language assistance, and remedial education—are also critical. They determine who can access and stay in the pipeline. U.S. semiconductor workforce training will fail if it assumes an ideal trainee without family responsibilities, debt, or educational barriers. Real workers lead complex lives when they arrive at the factory door.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Conference Board. (2025). The future of the CHIPS and Science Act.

McKinsey & Company. (2024). Reimagining labor to close the expanding U.S. semiconductor talent gap.

Mitchell Martin. (2025). Inside the semiconductor talent shortage—and how to stay ahead.

Semiconductor Industry Association. (2023). Chipping away: Assessing and addressing the semiconductor workforce gap.

Semiconductor Industry Association. (2024). 2024 State of the U.S. semiconductor industry.

U.S. Congress. (2022). CHIPS and Science Act of 2022.

White House. (2024). Fact sheet: Two years after the CHIPS and Science Act.

Wikipedia. (2025). 2025 Georgia Hyundai plant immigration raid.

Comment