The Trade Benefit Ratio Is the Missing Welfare Metric for an Era of Fragmentation

Input

Modified

Trade benefit ratio maps hidden partner losses Heterogeneity stems from supply diversity Policy and education: protect high-ratio sectors, diversify

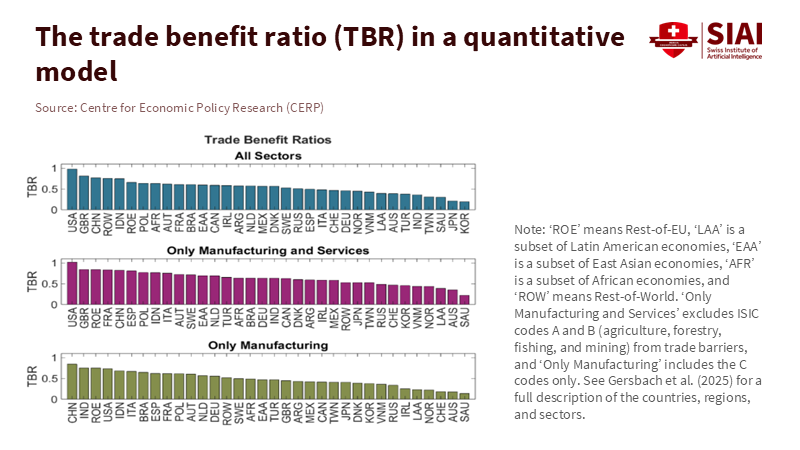

The key number to start the debate isn’t the tariff rate or the trade deficit. It's the trade benefit ratio. When a country disconnects from global trade, recent studies show that the losses abroad can match those at home. The United States has a trade benefit ratio close to 1, meaning its partners almost match the U.S. losses when the U.S. pulls back. In contrast, Japan and Korea have ratios around 0.2, indicating that their withdrawals cause much less harm to others. This isn’t just a statistic; it reveals which countries create value for the world through production networks and which do not. It also varies by sector, highlighting which industries provide significant external benefits. For any country currently weighing whether to let a vulnerable sector decline, the trade benefit ratio shows the hidden losses partners would incur if that sector were to disappear.

From Leverage to Welfare: What the Trade Benefit Ratio Really Measures

The trade benefit ratio resembles power, but it also serves as a welfare measure. It reflects how much value a country’s industries generate for others compared to what they generate at home. When the ratio is high, halting production impacts partners almost as much as it affects the home market. This shifts the focus of policy discussions. We should not only examine how much a sector raises domestic income; we should also consider how much it contributes to incomes abroad. This is crucial in an increasingly fragmented world. Estimates from the International Monetary Fund suggest that trade fragmentation alone could reduce long-term global output by up to 7% under severe scenarios. The combination of technology decoupling might push losses to 8-12% in some countries. These costs affect both sides of the divide. The trade benefit ratio shows how losses ripple through sectors and across borders.

Using the trade benefit ratio as a welfare metric highlights the external costs that traditional national accounting often overlooks. A country can rank in the middle for GDP but still have a high ratio if it hosts sectors that many others rely on. A small hub in precision tooling or specialty chemicals can support multiple foreign supply chains, even if it appears modest in local tax figures. The ratio captures that support effect. It also warns us about moral hazards in discussions about reshoring. Bringing production back home may make one country safer, but it often increases the trade advantage of remaining foreign hubs. This makes partners more vulnerable when the next crisis strikes. In short, the metric helps us understand the spillovers that markets usually assess only after a crisis.

Looking at sector details is key for policy. A single country can host both low-ratio and high-ratio sectors. Commodities with many nearby substitutes typically yield a low ratio. However, a specialized piece of advanced manufacturing equipment, a specific polymer, or a cutting-edge chip often results in a high ratio. Policymakers should not view these sectors as the same. The ratio urges us to protect sectoral public value, not just jobs. It also aids targeted cooperation. If a sector provides high external value, then aligning on standards, export licenses, or shared stockpiles can contribute more to global welfare than a tit-for-tat tariff response ever could. The trade benefit ratio transforms a strategy of threats into a strategy of stewardship.

Supply Diversity Explains Sector Gaps in the Trade Benefit Ratio

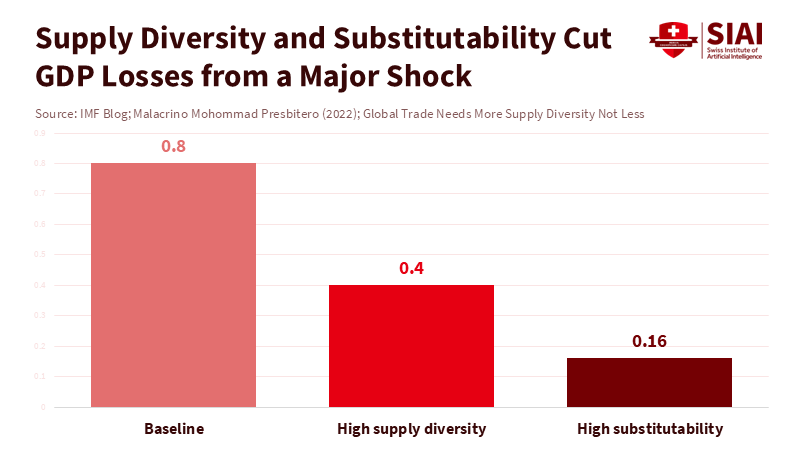

Why does the trade benefit ratio vary so much across sectors? The main reason is supply diversity and the ability to replace sources when buyers can easily switch to another country; a local shutdown results in only minor losses abroad. Conversely, when switching becomes challenging, the external damage increases. IMF simulations highlight this issue. In a scenario in which a single large input supplier faces a 25% labor shock, the average GDP falls by about 0.8%. If firms diversify their sources, this decline is nearly halved. If inputs are more easily replaceable, losses outside the affected country drop by about four-fifths. Currently, firms still show a strong preference for domestic sourcing; in the Western Hemisphere, 82% of intermediates are sourced domestically. Reshoring further reduces diversity and can raise the trade benefit ratio of the remaining foreign hubs.

Semiconductors illustrate this concept. Europe has set an ambitious goal: to reach 20% of global chip production by 2030. However, recent scrutiny by the European Court of Auditors suggests that this target is unlikely to be achieved under current plans. The implications go beyond just European risks. A high concentration in other regions means the trade benefit ratio for surviving hubs remains elevated. A disruption in one node can send shockwaves through the automotive, medical device, and cloud services industries worldwide. This is the hidden cost that partners bear when supply diversity falters. A policy that simply shifts production capacity from one ally to another within a bloc may change who holds leverage. Still, it does little to reduce the global ratio or protect partners when the subsequent shortage occurs.

Diversity is not just about having more factories. It also involves shared standards and design choices that facilitate easier switching. Automakers that reduce the number of unique chip variants and move toward standard microcontroller families essentially build substitutability into their systems. This decreases the sector's trade benefit ratio since the impact of any one plant becomes less critical. The lesson for the supply chain is clear: standardize inputs wherever safety allows, publish interface specifications, and invest in digital maps of multi-tier supplier networks so smaller firms can identify alternative sources. These steps mitigate external damage from local shocks and ease trade-related politics, since fewer buyers feel reliant on any single location. The trade benefit ratio serves as a scorecard indicating when these investments have paid off.

Policy and Education: Using the Trade Benefit Ratio to Cut Hidden Losses

Industrial countries should prioritize the trade benefit ratio in impact reviews. Any tariff, subsidy, export control, or merger policy affecting a high-ratio sector has cross-border implications. The proper evaluation is not only “what happens to domestic jobs and prices,” but also “how much partner welfare do we harm relative to our own.” Sometimes the response may still support a hardline stance. However, in many cases, it will favor maintaining at least a presence in high-ratio sectors, encouraging new entrants in friendly nations, and broadening the range of substitutes. The fragmentation of foreign direct investment raises the stakes even higher. IMF research estimates that long-term global output losses from FDI fragmentation could approach 2% of world GDP, placing a heavier burden on emerging economies that depend on external capital and expertise. This is yet another way that a sector's decline at home can negatively impact partners abroad.

Education can help make this understanding habitual rather than reactive. Introductory courses still teach trade benefits with two-country models. That’s fine, but they should also include input-output tables and a simple exercise: remove a high-ratio sector and observe how losses spread across partners. Incorporate case studies on vaccines, critical minerals, and semiconductors. Challenge students to calculate a "diversity index" for the same sector across two regions and connect it to the expected trade-benefit ratio. These activities make trade more relatable. They demonstrate that a plant closure isn't just a local issue; it’s a cost that appears in other places, often poorer ones, months later. If future managers and officials can foresee these costs, they will make better decisions.

Policymakers should anticipate and address key critiques. The trade benefit ratio relies on models and past input-output data. It doesn't account for finance, migration, or research connections. It can be misused to claim leverage or to overextend on subsidies. These are valid concerns, but shouldn’t lead to disregarding the metric. Address these issues by publishing the inputs, conducting sensitivity analyses, and pairing the ratio with qualitative data from businesses and customs records. Update it regularly and use it to identify where small public investments can significantly reduce partner risk—by funding standards, pilot programs, workforce initiatives, or co-investments that broaden supply. The aim isn’t to freeze the current maps but to lessen the external damage when they change.

We will continue to hear that the world is dividing into blocs. The thoughtful response isn’t to ignore it and build higher barriers. Instead, we should measure and manage the losses those barriers create for others and for ourselves. The trade benefit ratio is an essential starting point. It reveals that some sectors contribute far more to welfare than national accounts indicate. Supply diversity is the key lever to reduce external damage during shocks. The IMF warns that severe fragmentation could reduce global output by up to 7%. In comparison, technology decoupling could raise losses to 8-12% in some regions. This range should capture our attention. We need to use the trade benefit ratio to highlight high-value sectors, maintain critical capacity where it matters, invest in substitutes where possible, and prepare the next generation to view interdependence as a responsibility. If we do this, the next disruption will still cause harm. However, it will affect fewer partners for a shorter time and cause less lasting damage.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aiyar, S., Ilyina, A., et al. (2023). Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism (IMF Staff Discussion Note 2023/001). International Monetary Fund.

European Court of Auditors. (2025, April 28). Microchips: EU off the pace in a global race (Special Report 12/2025).

Gersbach, H., Maunoir, P. M., & Walsh, K. J. (2025, November 27). The economic value nations create for others relative to domestic gains (VoxEU column). Centre for Economic Policy Research.

International Monetary Fund. (2022, April 12). Global Trade Needs More Supply Diversity, Not Less (IMF Blog).

International Monetary Fund. (2023, April). World Economic Outlook, Chapter 4: Geoeconomic Fragmentation and Foreign Direct Investment. International Monetary Fund.

International Monetary Fund. (2023, January 16). Confronting Fragmentation Where It Matters Most: Trade, Debt, and Climate Action (IMF Blog).

Comment