Coalition Arithmetic and the Osaka Second Capital Bargain

Input

Modified

Osaka second capital now anchors a fragile coalition Capital shift could widen or rebalance regional education Classrooms can use this debate to teach coalition politics

Japan’s new government was formed with two seats short. After the October 2025 prime minister vote, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its new partner, the Osaka-based Japan Innovation Party (Ishin), held 231 of the 465 seats in the House of Representatives, just under the 233 needed for a majority. To fill that gap, they agreed on a confidence-and-supply deal based on twelve policy promises, three of which are non-negotiable. At the forefront is the Osaka second capital initiative: a plan to move part of Japan’s political center from Tokyo to the Kansai region. In return for backing Sanae Takaichi’s minority cabinet, Ishin sees Osaka's second capital status as the primary test of trust. The government’s survival now hinges on how far it goes to fulfill that promise in a Diet where every vote and every region matters.

This moment is about more than coalition numbers or city rivalries. It pushes Japan to decide whether decentralization will be seen as a narrow political exchange or as a broader public project that includes education. The Osaka second capital debate highlights ongoing tensions between Tokyo and the old capital belt of Kyoto and Osaka. Still, it also offers a chance to rethink the roles of schools, universities, and cultural institutions in national resilience. If Osaka is to share capital functions with Tokyo, the discussion should not end with relocating a few ministries. It should reshape how future voters learn about coalitions, regions, and the costs of maintaining power in a divided parliament. This makes the Osaka second capital story a fitting case for an education journal.

Osaka's second capital politics and coalition leverage

The new LDP–Ishin partnership is built on both weakness and ambition. Without its former ally Komeito, the LDP entered the prime minister vote with only 196 lower-house seats; Ishin had 35. Other parties and independents controlled the remaining 234, leaving Takaichi reliant on a partner whose support comes mainly from Osaka and the broader Kansai area. Together, they can muster 231 votes in the lower house. Still, Ishin has kept the option to walk away if key demands, including the promise to make Osaka a second capital, are not met. The agreement maintains some distance: Ishin holds no cabinet positions and can oppose specific bills while still backing the government in formal confidence votes. In this context, Osaka's second capital politics becomes less about a manifesto point and more a lever Ishin can pull whenever it wants to remind Tokyo where its survival rests.

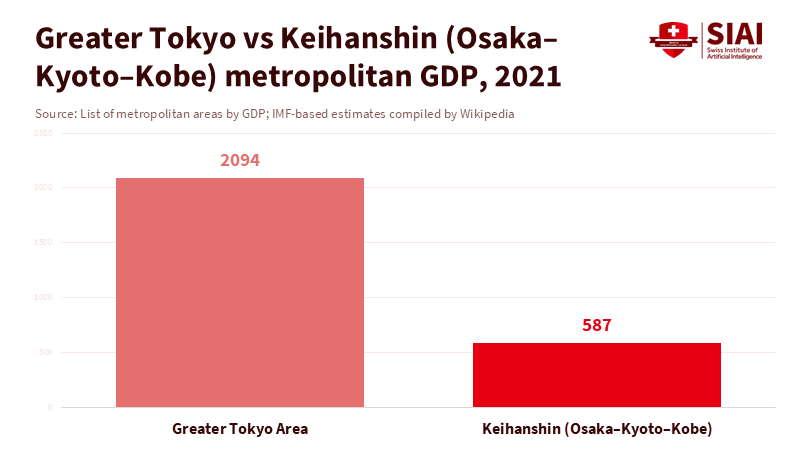

What Ishin is requesting is not a vague slogan. The Osaka prefectural government has spent years outlining a “second capital” vision with four roles: serving as an alternate location for core government functions during major disasters, hosting relocated agencies, becoming a growth hub for western Japan, and symbolizing a more balanced national structure. Osaka’s economic strength supports this claim. Official market reports show that its gross regional product was around US$360–370 billion in recent years, comparable to a mid-sized European economy. The wider Kansai metropolitan area has about 19 million residents. Tokyo still dominates, with an estimated metropolitan GDP exceeding US$2.5 trillion, making it one of the largest city economies globally. Yet, these numbers demonstrate that the Osaka second capital push is based on real capabilities, not just local pride. For Ishin, securing that status would solidify its influence long after this fragile coalition had ended.

However, the Osaka second capital bargain also tests how far territorial politics can stretch Japan’s party system. Ishin emerged as a regional reform force, promising to cut waste, reduce politicians’ perks, and shift power away from Tokyo. It has evolved into a national right-of-center party. However, its strongest support remains in Osaka, where it has promoted large urban renewal projects, the 2025 World Expo, and plans for an integrated resort with a casino. These projects have attracted investment and tourists, but they have also increased inequality, from luxury towers around Grand Green Osaka to the controversial eviction of the homeless population in Kamagasaki in preparation for the Expo. When Ishin demands Osaka's second capital status in exchange for keeping Takaichi in office, it connects this redevelopment agenda with a national coalition strategy. The danger is that Osaka's second capital politics become yet another tool for property-driven growth rather than a means to promote equal social and educational opportunities across regions.

Osaka is Japan's second-largest city and has a regional education gap

Education policy illustrates why the Osaka second capital debates are significant far beyond the Diet’s discussions. Japan is preparing a major high school tuition reform in 2026 that will make public high schools tuition-free nationwide and provide subsidies for private schools. As of 2023, the average total costs for three years of high school were about 1.78 million yen in public schools and 3.08 million yen in private schools, including tuition, admission, and facility fees. Approximately 65 percent of high school students attend public schools. Still, in large metropolitan areas, the share of private school students already exceeds half. Osaka moved ahead of most prefectures, using local subsidies to make high school tuition effectively free. This move shifted enrollment toward private schools, left some public schools underenrolled, and led to closures. In some cases, rising private-school fees absorbed much of the financial relief for families. The outcome is a more unequal situation within a city that is now central to Osaka's second capital politics.

The Osaka second capital plan would add another layer to these trends. Moving parts of the central government to Osaka would bring civil service jobs, infrastructure, and prestige. It could also increase research funding, international programs, and specialized institutions in Kansai. Without careful planning, this could widen the gap between high-pressure metropolitan systems and struggling rural schools, as top teachers and students flock to a few large hubs in search of opportunities. Universities in Tokyo and Kansai already compete for limited public funds; an Osaka second capital strategy focused on visible prestige projects could turn that rivalry into a zero-sum game. The pressures of a fragile coalition might push towards headline-friendly initiatives such as new government campuses, conference centers, and elite institutes, rather than the slow, steady growth of teacher training or regional vocational schools.

However, Osaka's second capital politics could also be directed towards positive outcomes. Suppose the government ties capital relocation to a broader regional education approach. In that case, it can transform a narrow coalition concession into a national experiment in balanced development. Decisions about where to place relocated agencies could be related to clusters of public universities and technical colleges across Osaka, Kyoto, Kobe, and neighboring cities. Scholarship programs could encourage students from rural prefectures to study in Kansai and return home with new skills, rather than staying in Tokyo. The expanded tuition subsidies now being introduced nationwide could be adjusted so they do not support only private school growth in affluent areas, but also help public schools serving smaller towns. The Osaka second capital debate has the potential to either widen the gap between leading cities and the rest or provide a framework for distributing educational resources more equitably in the long run.

Teaching coalition literacy through the Osaka second capital debate

For educators, the most significant aspect of Osaka's second capital politics lies in the classroom. Japan’s political scene has shifted from long-term one-party dominance to a more fragmented environment, where confidence-and-supply deals like the current LDP–Ishin agreement may become more common. Research on coalition and minority governments indicates they tend to have shorter lifespans, more policy deadlock, and a greater demand for transparency. Students do not need to understand these dynamics through abstract models. The Osaka second capital issue offers a real case study of how regional parties negotiate, form, and uphold policy agreements, and how promises can conflict with financial or diplomatic constraints. Civic education can draw on this Osaka second capital story to promote “coalition literacy”—the ability to read coalition agreements, follow their progress, and grasp why governments make trade-offs that may initially seem unclear.

This effort does not involve instructing students on which side to support. Instead, it focuses on illustrating how power is exercised when no party can govern alone. The Osaka second capital debate encompasses many themes a modern civics curriculum already includes: decentralization, disaster readiness, budget choices, the ethics of moving ministries, and the rights of regions that feel overlooked. It also connects domestic politics to foreign policy. Takaichi’s coalition decisions overlap with a firmer stance on China and an accelerated defense build-up. These changes have already influenced university research collaborations, international student movements, and the politics surrounding joint institutes. By using Osaka's second capital politics as a teaching instrument, students can see how decisions made in the Diet impact admissions policies, language programs, and the financial health of regional universities that rely on international enrollment.

Policy-makers can assist by providing educators with better resources. Coalition agreements are often dense and legalistic, released in a way that makes it challenging for non-specialists to understand. The Osaka second capital sections could be summarized in clear Japanese, along with notes detailing region-by-region impacts that schools and universities can utilize in discussions and project-based learning. The ministries responsible for education and internal affairs could fund collaborative programs that bring together students from Tokyo, Osaka, and other prefectures to simulate coalition negotiations around capital relocation, budget compromises, and tuition reforms. By treating the Osaka second capital plan less as a private deal among party elites and more as a well-structured learning opportunity about how complex democracies function in practice, the government can open it up.

Japan’s coalition era is still in its early stages, and questions about the Osaka second capital will likely not be the last example of regional influence in national politics. Critics argue that using capital status as a bargaining tool risks fostering local nationalism, reinforcing property-driven development, and diverting attention from urgent national issues like inequality, climate change, and demographic decline. Those concerns are valid. However, there is also a risk in pretending that coalition compromises can be kept away from public discussion and civic education. When the logic of parliamentary arithmetic is obscured, it becomes easier for populists to frame every concession as a betrayal. When teachers help students trace how negotiations over Osaka's second capital arose from specific seat counts, party history, and policy goals, they prepare a new generation to question, critique, and improve the agreements made in their name.

In the end, the Osaka second capital bargain may only be temporary. Coalitions shift, leaders change, and policy commitments can be weakened or abandoned. The more lasting impact will be whether Japan seizes this moment to foster a more regionally balanced, politically informed society. The story began with a stark figure—231 seats, where 233 were needed—and a bold demand from an Osaka-focused party that once defined itself against Tokyo. The future should not be left solely to party strategists. It should include teachers, university leaders, and students who see the Osaka second capital debate as a living textbook about power, location, and responsibility. If they embrace that opportunity, a fragile coalition could still pave the way for a stronger democratic classroom.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Crabtree, C & Golder, S 2025, ‘Takaichi’s Japan enters an era of fragile coalitions’, East Asia Forum, November.

Economy News 2025, ‘Japan’s first female prime minister all but certain — Takaichi navigates fragile coalition’, The Economy, October.

Konishi, R 2025, ‘Japan’s equal educational opportunity faces funding dilemma’, East Asia Forum, November.

Le Monde 2025a, ‘A destitute Osaka district faces erasure’, March.

Le Monde 2025b, ‘World Expo symbolizes Osaka’s revival’, April.

Nishimura, R 2025, ‘The future of the LDP–Ishin partnership’, Tokyo Review, November.

Osaka Prefectural Government 2022, ‘Osaka market report’, Osaka Prefecture.

Osaka Prefectural Government 2023, ‘Vision for the second capital – Osaka’, Osaka Prefecture.

Reuters 2025, ‘Japan’s new PM Takaichi secures backing from Osaka-based Ishin party’, October.

South China Morning Post 2025, ‘Could Osaka be Japan’s second capital?’, November.

Wikipedia 2025, ‘Japan Innovation Party’, Wikimedia Foundation.

Comment