Bring Profits Home: Why the Global Minimum Tax Supports America's economic goals and investment climate

Input

Modified

A 15% global minimum tax cuts shifting and anchors profits to real activity More onshore earnings strengthen in-house finance and level competition; havens shrink The U.S. should adopt the floor, add a domestic top-up, and pair it with simple investment credits

The most significant number in global corporate taxation today is $1 trillion. This is about how much profit multinationals moved to tax havens in 2022, which accounts for roughly 35% of all profits reported outside their home countries. It also represents nearly 10% of global corporate tax revenue lost each year. When the United States backed away from the global minimum tax, it did not protect American competitiveness; it maintained that trillion-dollar leakage. Honest firms had to compete on an uneven playing field, while those finding ways around the rules were rewarded. This also undermined the domestic investment story that many claim to support. By reducing the benefits of moving profits, the global minimum tax encourages earnings to return to the countries where real economic activity occurs. This isn’t just a change in taxes; it is a shift in finance. It affects where retained earnings are held, how in-house projects get funded, and which financial centers succeed.

What the Global Minimum Tax Actually Does

The global minimum tax establishes a 15% minimum effective tax rate for large multinationals with annual revenues above €750 million. It does this through a set of coordinated rules (IIR, UTPR, and QDMTT). This design narrows the gaps in effective rates across countries. It makes it more challenging to place paper profits in low-tax areas while recording expenses in higher-tax markets. The OECD estimates that narrowing these differences could increase global corporate tax receipts by $155–$192 billion annually once the system is implemented. These gains arise from two sources: top-up taxes and reduced profit shifting.

This reform is not merely theoretical. Major jurisdictions representing most global multinationals have made progress. EU members, the UK, Canada, Japan, and many more have begun implementation starting in 2024. By late 2025, research summarized on VoxEU, drawing on official trackers, indicates that many countries already have their rules in place or in progress, with significant coverage anticipated even if some large economies fall behind. The structure's idea is that if one jurisdiction chooses not to collect, others can impose a top-up, significantly lessening the incentive to undercut the minimum rate. This feature means the regime can remain effective even without universal participation.

Profit Shifting Distorts Investment—The Hidden Cost

Profit shifting is not a minor issue. It alters how firms respond to taxes on real activities. New evidence indicates that focusing only on firms that report positive taxable income underestimates profit shifting by about half, as many multinationals transfer all their profits out of high-tax countries. Because of this, the apparent sensitivity of investment to tax rates appears low, as the effective rate has already been reduced through avoidance strategies. Reducing profit shifting can raise effective rates toward statutory rates and eliminate a hidden subsidy that benefits sophisticated avoiders over firms that keep profits where they are generated.

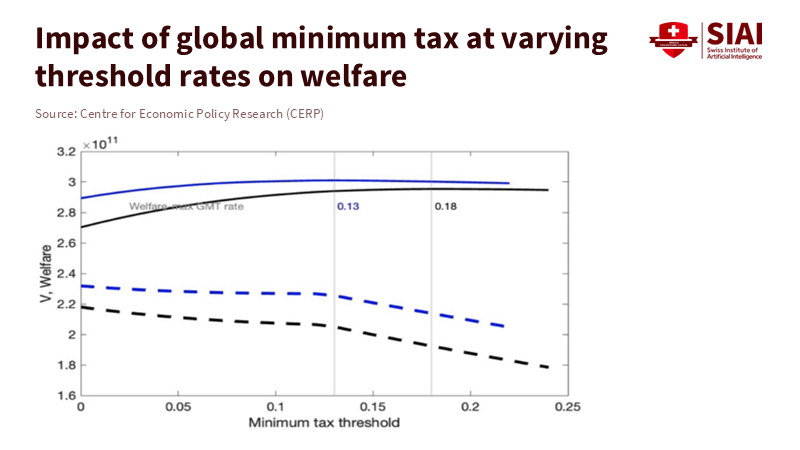

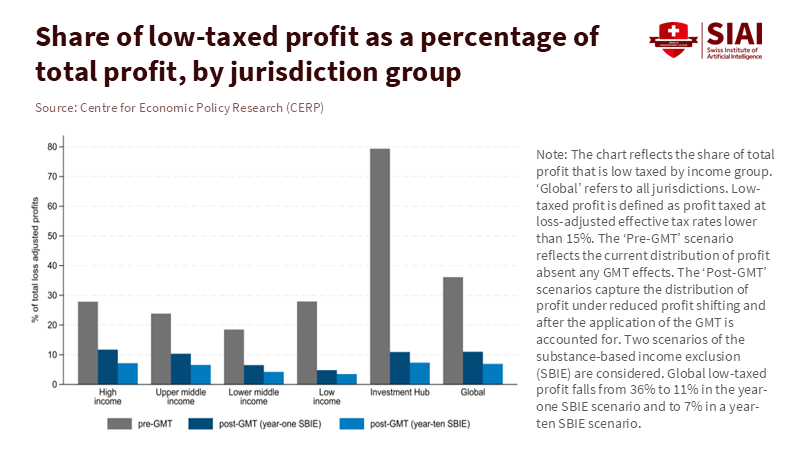

A second distortion is the real resource cost of avoidance. Multinationals invest in “tax-avoidance assets”—structures, contracts, and IP arrangements that are costly to establish but inexpensive to operate at scale. These past investments only pay off if profits can continually be sent to havens. A global minimum tax eliminates that benefit. The OECD’s latest assessment predicts an approximately 80% drop in low-taxed profit over time and around a 50% reduction in shifted profit, with investment hubs losing about 30% of their tax base as artificial profit booking declines. This change realigns where profits are recorded and, over time, reorients management's focus and legal spending toward essential operations rather than money-seeking structures.

Why the U.S. Exit Is Self-Defeating for Investment and Finance

In January 2025, the United States announced that the OECD agreement “has no force or effect” domestically and later urged G7 partners to exempt U.S.-parented groups from the main rules. While this position seems like a safeguard for U.S. companies, it actually undermines a framework that would bring profits back to where American production, design, and sales genuinely happen. Without the minimum tax, U.S. firms retain a larger portion of earnings in booking centers. With it, more earnings would stay onshore, increasing retained earnings—the most dependable source of internal financing for investment—available within the United States. The reasoning is straightforward: if exploiting the rate gap yields less benefit, firms are more likely to report profits where real activities occur, generating the funds necessary for capital expenditures, research and development, and training domestically.

This retreat also benefits financial centers that rely on easily movable profits. EU Tax Observatory data show how substantial these flows are: around $1 trillion in shifted earnings in 2022, with U.S. multinationals accounting for roughly 40% of the total. Some hubs convert those flows into exceedingly high per-capita corporate tax receipts. Suppose the global minimum tax reduces profit shifting. In that case, the immediate losers will be those hubs, while the winners will be the countries where activities take place. For a country aiming to “bring industry home,” backing away from the global minimum tax runs counter to this objective. It preserves cash in tax havens rather than supporting the financial stability of American factories, laboratories, and suppliers.

The Indirect Effects: Capital Costs, Competition, and the Geography of Finance

The direct impact of a global minimum tax is a lower after-tax return on profits booked in low-tax areas. The indirect effect is a shift in relative financing conditions. As more profits are recorded in real activities, the domestic share of retained earnings increases, thereby reducing many companies' reliance on outside funding. This is particularly important for mid-sized and privately held companies, which face higher costs and weaker collateral than larger publicly traded peers. OECD research also finds that reducing adequate rate gaps by about 30% makes non-tax factors—such as skilled labor, energy costs, logistics, and the rule of law—more critical in location decisions. This is sound industrial policy. Competing based on actual advantages is more durable than competing based on accounting tricks.

There is another secondary effect: the cost of capital for habitual shifters will rise to match the cost faced by firms that have never shifted. Evidence summarized on VoxEU shows that shifters appear less responsive to changes in statutory rates because their accurate effective rates are already low. If a minimum floor is enforced, their investment decisions will start to resemble those of their peers. This levels the playing field within sectors and reduces a trend where the best tax strategists win contracts over more productive rivals. Over time, the reform lowers wasteful spending on avoidance. It reduces the preference for intangible-heavy models created primarily to shift profits rather than serve customers.

Policy Steps Now: Make the Floor Work for, Not Against, U.S. Industry

First, re-engage and cooperate. Suppose the U.S. adopts the global minimum tax framework. In that case, it can implement a Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-Up Tax to raise revenue domestically rather than allowing others to impose top-ups under the UTPR. The OECD estimates that most of the additional revenue under this system will come from top-ups, so there is no reason to leave that money on the table. A domestic top-up, along with targeted investment credits—transparent, budgeted, and properly scored, rather than customized rulings—would keep both revenue and investment incentives aligned with national goals.

Second, protect the floor's integrity. The regime includes a “substance-based income exclusion” that allows a normal return on payroll and tangible assets. This feature prevents penalizing genuine activities, but if exclusions or new credits become loopholes, the old issues will reemerge. Independent evaluations have warned that overly generous exclusions and complicated credits could undermine expected benefits. The solution is straightforward: keep credits transparent, cap their value, set expiration dates, and conduct audits. A streamlined menu of precise, general instruments will do more to promote investment than a complicated system of customized tax formulas.

Third, connect tax and capital markets. If the goal is to enhance internal financing for productive investments, pair the adoption of the minimum tax with steps that encourage the quick reinvestment of repatriated profits into capital expenditures. Two practical actions could include accelerated loss carryforwards for net-zero projects and workforce training, as well as safe-harbor expensing for qualifying intangible investments linked to domestic initiatives, such as software and data infrastructure. These measures will reduce the cost of capital for projects that enhance long-term productivity without reopening the door to shifting profits overseas. The aim is to quickly transform the shift from paper profits to real profits into real investments.

Fourth, be straightforward about trade-offs. A minimum floor raises effective rates for the most aggressive avoiders; some of their projects may no longer be financially viable. However, the benefits include a fairer market, lower compliance costs, and more neutral tax treatment across business models. OECD analysis suggests that as differentials decrease, capital allocation improves, and more profits are taxed where actual activities occur. This is a win for industrial policy disguised as tax reform.

The initial figure of $1 trillion in shifted profits highlights what is at stake. Abandoning the global minimum tax solidifies that flow and keeps cash in places where little real work is done. Embracing the minimum changes to this trend. It returns profits to where factories operate, engineers create, teachers instruct, and service teams engage with customers. This shift is not about punishment; it is about alignment. It aligns taxes with activities, competition with productivity, and finance with investment. For countries striving for more domestic capacity, improved supply chains, and sustainable growth, the decision is evident. Build on the global minimum tax, refine it as necessary, and pair it with clear, budgeted incentives. Bring profits home and put them to work.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. “Deal to force multinational companies to pay a 15% minimum tax is marred by loopholes, watchdog says.” Oct. 2023.

CEPR VoxEU (Bilicka, Devereux, Güçeri). “Reforming international taxation: Balancing profit shifting and investment responses.” Nov. 30, 2025.

CEPR VoxEU (Hugger, González Cabral, Bucci, Gesualdo, O’Reilly). “How the Global Minimum Tax changes the taxation of multinational companies.” Jun. 22, 2024.

EU Tax Observatory. Global Tax Evasion Report 2024. Oct. 2023.

OECD. Economic Impact Assessment of the Global Minimum Tax—Summary. Jan. 2024.

PwC. “Pillar Two Country Tracker” (implementation status). Accessed Nov. 2025.

Reuters. “Trump effectively pulls US out of global corporate tax deal.” Jan. 21, 2025.

U.S. Treasury. “G7 Statement on Global Minimum Tax.” Jun. 28, 2025.

Comment