Green Bonds Are Not a Costume. They Are a Contract

Input

Modified

Green bonds are contracts, not labels; use-of-proceeds rules cut firms’ carbon intensity The greenium is small, but credibility and disclosure drive real operational change Tight EU standards can scale issuance into measurable emissions declines by 2030

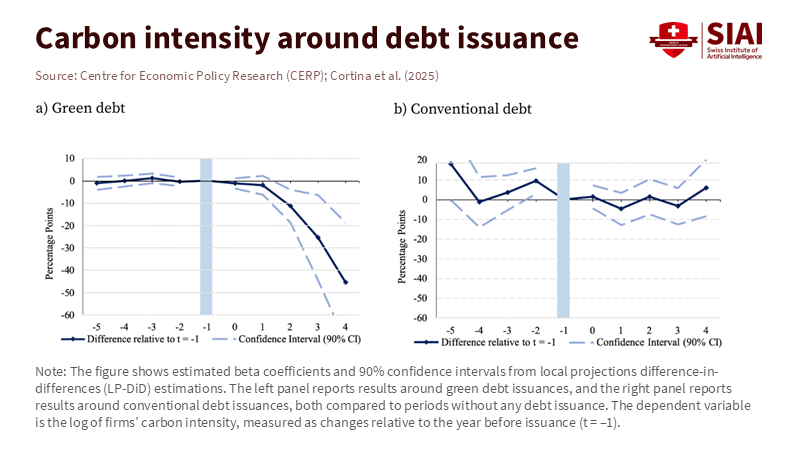

Within four years of issuing green debt, companies reduce their carbon emissions per euro of revenue by about half. Firms that issue conventional debt do not see such changes. This isn't just branding; it's a fundamental shift in how major emitters finance and manage their operations, happening on a large scale, primarily in Europe. In 2024, green bonds accounted for 6.9% of all EU bond issuance. That share is increasing, and the European Green Bond Standard now ties proceeds to uses that match the taxonomy. With a small "greenium," investors accept slightly lower yields, sending a clear price signal. The key debate for 2025 should not be whether green bonds are just marketing. It should focus on whether the additionality of green bonds is strong enough and fast enough to influence Europe’s emissions trajectory over the next decade. Evidence suggests it can, provided policies support the contract, making policymakers feel their actions matter.

Green bond additionality starts with obligation, not optics

The primary feature of a green bond is the use-of-proceeds covenant. Money must go to activities that reduce emissions or protect the environment. In the EU, the new European Green Bond (EuGB) label ties 100% of proceeds to taxonomy-aligned activities, allowing limited flexibility to keep issuance practical while addressing data gaps. This limits discretion and raises stakes for issuers. It also gives investors something concrete to check. When an issuer agrees to replace a gas boiler fleet, retrofit a plant, or fund grid-ready renewables, the bond indenture and post-issuance reporting make that promise enforceable in a way that general corporate debt does not. The rule is straightforward: optics do not build heat pumps; obligations do. This transparency reassures investors about the credibility of their investments.

The strongest argument for adding green bonds is not moral but empirical. A large global sample shows that green borrowers tend to be the big emitters that matter most. After they issue bonds, their carbon intensity significantly drops compared to similar firms in conventional markets. This pattern appears across bonds and loans and is especially pronounced among large hybrid issuers accessing both green and traditional debt. This is where we want the effect: at companies whose choices significantly affect emissions. Europe is leading this boom in corporate green borrowing, which means it could see the operational gains first if the rules stay strict.

The price question: is there a greenium—or just a label?

Skeptics argue that if green bonds are meaningful, they should cost issuers less. Data show a slight but notable "greenium." Studies comparing matched bonds find that green bonds typically have average yield discounts of three to six basis points compared to conventional ones. Recent frameworks in Europe for "twin bonds" suggest even smaller premiums—often just one to two basis points—when everything except the label is held constant. This isn’t a giveaway. It represents investors’ willingness to pay a little more for a credible environmental purpose and for the reporting they can present to their clients and regulators.

However, lower funding costs are not the main reason for green bond additionality. Reporting, external review, and project selection increase issuance costs. For many firms, the net price advantage is slim after fees. The real value lies in the disciplined capital allocation enforced by the covenant. Investors are willing to accept a modest yield trade-off because it lowers the risk that their funds support stranded assets or regulatory missteps. In Europe, the EU GB rulebook and taxonomy provide a common language for "what counts." When supply is credible, demand remains strong; various surveys show significant interest even during macroeconomic disruptions, although issuance slowed in 2025 due to policy uncertainties and interest rates. The structure is resilient enough to last beyond a single policy cycle because it's rooted in issuer-investor incentives rather than mere slogans.

Will the additionality of green bonds influence Europe’s emissions by 2030?

The near-term emissions situation is mixed. Global energy-related CO₂ reached a new high in 2024. Yet, advanced economies, including the EU, reduced emissions in 2023, and the EU ETS recorded a 5% drop in 2024. Germany’s emissions fell to a 70-year low, though some of the reduction stemmed from weak industry rather than structural changes. The test for green bond additionality is whether the EU's use-of-proceeds constraint and scaling requirements can convert short-term declines into lasting operational improvements. Evidence supports this: across a wide range of companies, those that issue green debt reduce emissions intensity, while similar firms using conventional debt do not. A Bank for International Settlements study confirms this trend: green bond issuance is linked to later emissions reductions, with more potent effects in countries with strict policies. Europe is such a place.

Scale matters. Green bonds accounted for 6.9% of EU issuance in 2024, with a record USD 1.05 trillion of aligned sustainable debt priced worldwide across green, social, and sustainability-linked categories. Europe’s share has been significant, and its frameworks are now the global standard. If the average carbon intensity of green borrowers declines sharply within four years and the proportion of green finance in total issuance continues to rise, the cumulative effect by the early 2030s could be substantial, even if the greenium remains modest. This does not imply that correlation equals causation. It highlights a strong connection between credible profit constraints, increased market share, and measurable operational changes at firms, suggesting that appropriate regulatory guidelines can translate that connection into broader outcomes. This outlook fosters confidence in the long-term positive impact of green bonds.

Design for impact: making the contract meaningful within firms

Three features enhance green bond additionality—first, hard alignment. The EuGB rule mandates that proceeds be used to fund taxonomy-aligned activities, thereby limiting flexibility. This eliminates weaker projects from consideration and, over time, improves the audit process—second, comparable disclosure. Post-issuance allocation and impact reports must utilize standard metrics and verification. Markets have learned the costs of vague promises; "twin bond" structures show that when the only difference is the label, investors will measure it down to the basis point, third, credible penalties. Sustainability-linked bonds include coupon increases if targets are missed. While these bonds differ from use-of-proceeds green bonds, the principle remains: failure should increase the cost of capital for future labeled issuance and the issuer’s entire curve. Europe’s framework is already progressing in this direction through supervision, taxonomy guidance, and investor oversight.

Implementation is where markets encounter challenges. Technical difficulties persist: the taxonomy's usability, the availability of Scope 3 data, and the risk that complex templates deter mid-cap issuers. Yet investor demand has remained strong when credibility is established, and Europe’s disclosure practices have improved. The policy challenge is to reduce friction without undermining the covenant. This involves publishing specific examples of taxonomy-aligned capital expenditures, standardizing impact metrics, and allowing limited flexibility as pipelines develop. It also means preserving the label's integrity during periods of weak issuance. A temporary drop in 2025 volumes should not prompt a return to vague "sustainable" labels. The contract must remain robust, ensuring that the bond is a financing tool with substance, not just a story with illustrations.

What educators, administrators, and policymakers should do now

Education systems shape capital and ideas. Universities prepare CFOs and engineers who will decide whether green bond additionality becomes the norm or fades away. Business schools should integrate use-of-proceeds finance into core corporate finance, rather than confining it to elective ESG courses. Teach the bond math alongside the plant retrofit case. Public policy programs should incorporate EU green bond documentation and taxonomy criteria in their practical exercises so future regulators and analysts can read—and create—credible frameworks. These skills are valuable: matching projects to eligibility criteria, estimating lifetime emissions reductions, and structuring impact reports that investors can evaluate. They are not soft skills; they are essential tools for modern capital allocation under climate constraints.

Administrators in schools and universities should also get involved. Campus energy retrofits, district heating systems, and small renewable projects are ideal use-of-proceeds projects that deliver measurable benefits in bill savings and reduced emissions. Public universities can lead local initiatives and set an example. Policymakers should support this by ensuring the EuGB framework remains stable, expanding sector guidance, and providing standardized reporting templates for smaller issuers. On the investor side, public asset owners should clarify that they will accept a fair greenium when the covenant is credible and the reporting is transparent. This aligns incentives from the lecture hall to the trading desk. If we teach students that rules and reputations matter, our bond markets should reflect the same principle.

Anticipating tough questions

“Is the greenium significant enough to matter?” Yes and no. A three-basis-point discount won’t rebuild a factory. However, it indicates investor interest in credible transition capital expenditures and slightly lowers the average cost of capital. Over an extensive funding program, a few basis points can add up. More importantly, the covenant itself influences what gets financed. In corporate operations, constraints can be more effective than subsidies. A small price signal, combined with a binding use-of-proceeds rule, can redirect billions to where they're needed most. Europe’s 2024 issuance mix shows the base is expanding.

“Is this just correlation?” Healthy skepticism is essential. Yet multiple studies now find that green borrowing is consistently followed by improvements in operational emissions, even with suitable controls. The effects are most pronounced where policy is strict, reporting is consistent, and investors can verify fund usage. This accurately describes today’s EU environment. Meanwhile, emissions from the ETS on the continent fell 5% in 2024, and EU-wide emissions dropped sharply in 2023. Green bonds did not solely cause those declines, but they are a pathway for policy and capital to converge. When covenants and disclosures increase the cost of greenwashing, the market regulates itself. That isn’t correlation; it’s building institutions.

The right question in 2025 isn't whether green finance has lost relevance. It's whether we will maintain green bond additionality tightly enough to turn a financial label into a substantial operational change over the next decade. The progress thus far is encouraging: Europe is leading in issuance, investors accept a modest greenium, and firms' carbon intensity falls after they borrow green, while conventional borrowing does not change the curve. Markets function effectively when contracts are clear and monitored. Suppose we uphold strict use-of-proceeds guidelines, compatible reporting, and credible penalties. In that case, the bond market can accelerate Europe’s long-term emissions reduction in the critical five- to ten-year window. The benefit is not a press release; it is a lower energy bill for a school, improved emissions at a plant, and a grid that can support more clean energy. The label alone does not achieve that; the contract does.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AXA Investment Managers. (2025, January 22). The good, the bad, the opportunities: green bonds in 2025.

Bank for International Settlements (Demski, J. et al.). (2025). Growth of the green bond market and greenhouse gas emissions. BIS Quarterly Review.

CEPR VoxEU (Cortina, J. J., Raddatz, C., Schmukler, S. L., & Williams, T.). (2025, December 1). Green versus conventional corporate debt: Financing choices and climate outcomes.

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2025, May 31). Global State of the Market 2024.

European Environment Agency. (2025, July 1). Green bonds (8th EAP indicator).

European Parliament (Legislative Train). (n.d.). Establishment of an EU Green Bond Standard.

ESMA. (2023, October 6). Issuers’ potential benefits from an ESG pricing effect.

IEA. (2024, March 1). CO₂ Emissions in 2023 – Analysis.

IEA. (2025). Global Energy Review 2025: CO₂ emissions.

Nature / Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (Zhou, D.). (2024). Why issue green bonds? Examining their dual impact on environmental protection and economic benefits.

OECD. (2024, March 11). Sustainability-linked bonds: Design and incentives.

Panizza, U. (2025). The Sovereign Greenium: Big promise but small price effect. Graduate Institute Working Paper.

Reuters. (2025, April 4). EU carbon market emissions drop 5% in 2024, on track for 2030 target.

Responsible Investor. (2025, September 24). EU Green Bonds stocktake: Strong investor demand but technical hurdles persist.

SSRN (Beyer, A. et al.). (2024). Who pays the greenium and why? Average greenium ≈ −3 bps.

Comment