China Climate Leadership After Paris: Why 7 to 10 Percent by 2035 Can Be a Floor

Input

Modified

China’s clean-energy surge makes the 7–10% by 2035 a floor, not a ceiling Wind, solar, and EV scale are bending emissions down despite coal capacity With the U.S. leaving Paris, China can anchor progress if grids and storage keep pace

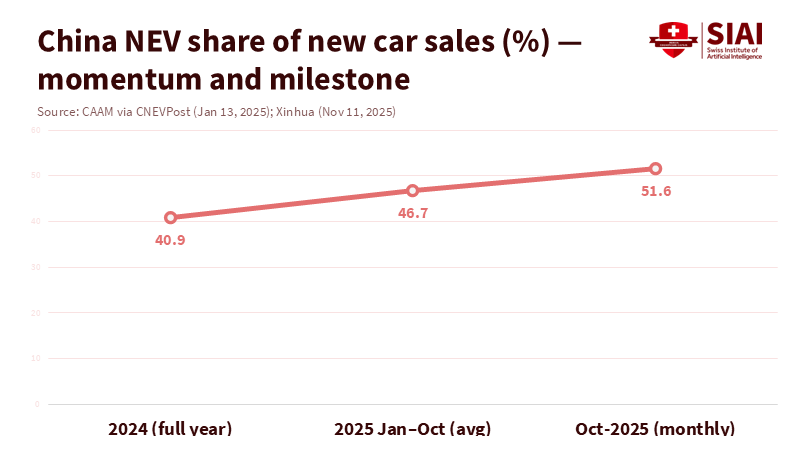

It is rare to witness a country change its emissions trends in real time. Over the last 18 months, China’s carbon dioxide emissions have leveled off or declined, even as electricity demand increased. The reason is straightforward: a record clean energy surge. In 2024 alone, China added over 250 gigawatts of solar power and tens of gigawatts of wind power. It continued building at this pace into early and mid-2025. The new energy supply replaced coal generation and helped prevent power sector emissions from rising. At the same time, electric vehicles reached a significant milestone, accounting for more than half of new car sales each month. In a context where the United States has again moved away from the Paris Agreement, China’s climate leadership has yielded tangible results, not just words. Beijing’s new commitment to reduce economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions by 7 to 10 percent below peak levels by 2035 is not the limit. It is the foundation for the next phase of global progress.

The new baseline for China's climate leadership

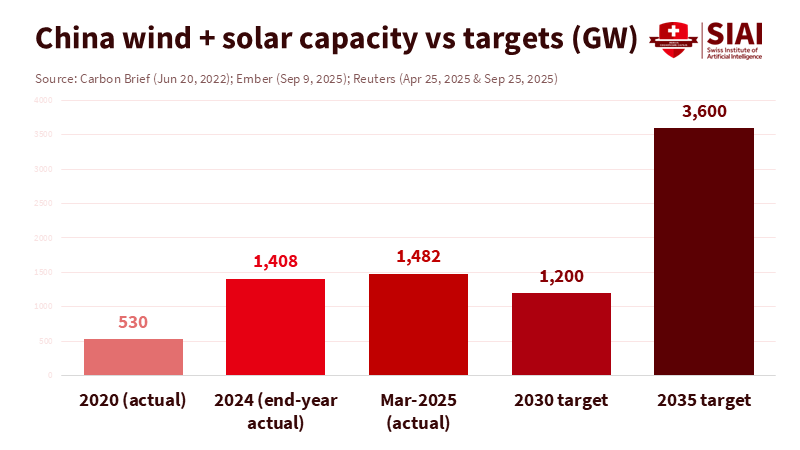

Beijing’s 2035 plan includes three key targets. First, it aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 7 to 10 percent below peak levels by 2035. Second, it seeks to achieve a non-fossil share of energy consumption above 30 percent. Third, it plans to expand wind and solar capacity from 2020 levels to 3,600 gigawatts by 2035, a six-fold increase. These targets matter because they are clear and achievable in the near term. They also build on real developments. China reached its previous goal of 1,200 gigawatts of wind and solar by 2030, about six years early. Analysts across NGOs, industry, and multilateral organizations now believe the 3,600 gigawatt target is attainable if current construction rates persist, particularly as grid integration improves. With emissions stabilizing since early 2024 and declining in some areas in 2025, the new commitment reinforces an ongoing trend. It indicates a shift from intensity targets to actual reductions while solidifying clean energy capacity that can support industry and transportation without causing a resurgence in coal use.

A leadership role is not only about domestic emissions. It also involves market signals and trade. China now leads the world in new solar capacity and dominates global electric vehicle production. As factories scaled up, battery prices decreased and exports of affordable electric vehicles and grid components promoted wider adoption. In 2024, China produced over 12 million electric cars and captured a large share of electric vehicle exports. By late 2025, new energy vehicles represented more than half of monthly sales. This market growth benefits everyone. It lowers costs for schools, hospitals, and local governments purchasing buses or rooftop solar beyond China’s borders. It also creates opportunities for other countries to decarbonize more rapidly, even as some major nations withdraw from the Paris Agreement.

Industrial policy makes the pledge achievable

Critics claim that the 7-10% target is conservative. They are correct. However, they overlook the benefits of this. Conservative targets combined with strong industrial policies can lead to exceeding expectations. China’s solar manufacturing, power-electronics supply chains, and ultra-high-voltage transmission capabilities are now extensive and scalable. The country invested over $600 billion in clean energy in 2024, far surpassing any other market. This scale encompasses more than just panels and turbines. It includes inverters, transformers, storage systems, and grid software. The shift to electric vehicles provides another advantage: it reduces oil demand. When electric cars account for over 50 percent of new sales, growth in oil consumption for road transport can stabilize and eventually decline. This shift in liquid fuel demand complements the transition from coal to cleaner power generation sources. Together, these developments make the 2035 target both realistic and likely to be increased in the next five-year plan if emissions continue to fall.

The lasting advantage now lies in speed. In 2024, wind and solar installations hit record levels. In 2025, monthly additions matched the electricity consumption of mid-sized countries. Recent analyses show emissions declining year-on-year in early 2025 and remaining stable or decreasing through the third quarter. This demonstrates what industrial capacity can achieve when it aligns with policy. It turns targets into minimums. None of this ignores the engineering challenges ahead. Reductions in curtailment are necessary. Grids need to be strengthened. Large-scale deployment of storage systems, including pumped hydro and batteries, is essential. However, these challenges are recognized bottlenecks that are now prioritized in planning and investment. If grid upgrades keep up with generation, the limitation will shift from hardware to operations and data.

Addressing the coal critique without avoiding reality

There is a brutal truth: coal construction increased in 2024, with new projects being initiated and old ones revived. This poses challenges for leadership claims. It should. China still generates most of its electricity from coal, and the need for reliability amid volatile growth keeps capacity margins high. However, capacity does not equate to generation. The utilization of the coal fleet can decline even as its overall capacity expands if wind, solar, and nuclear sources provide more hours of energy. We have started to see this as clean energy output grows. New coal units are often sized and located as peakers or grid-stability assets. At the same time, transmission adjustments, demand response, and storage catch up. The policy goal is to maintain that role, keep capacity factors low, and prevent carbon lock-in through strict runtime limits, increased coal-to-gas transitions where pipelines exist, and aggressive upgrades for flexibility.

The international situation is mixed but improving. Since Beijing committed in 2021 to stop building new coal plants abroad, many projects have been cancelled. However, some projects, especially those related to mining and metals in Southeast Asia, are still moving forward. The gap between commitments and actions has narrowed in 2025, as cancellations accelerated again, though loopholes remain. Here, China’s climate leadership should be assessed based on financial flows and equipment exports as much as on statements. The trend looks encouraging: for the first time, Chinese spending on overseas wind and solar projects appears to have surpassed that on fossil fuel projects, even as some off-grid coal remains in play. The policy approach is straightforward. Tighten guidelines for state lenders and state-owned enterprises on overseas coal. Link export credits more closely to storage and grid projects. And ensure that Belt and Road energy initiatives align with the net-zero path that domestic markets are already pursuing.

What educators and policymakers should do next

Education systems play a vital role in any energy transition. In a world where the United States has again distanced itself from the Paris Agreement, universities, vocational schools, and colleges can anchor long-term progress. Three priorities stand out—first, workforce development. China’s rapid expansion highlights a global shortage of power engineers, grid planners, and technicians capable of deploying storage and integrating variable renewable energy sources. Education ministries should fund applied programs in power electronics, grid cybersecurity, and battery recycling. International partnerships can design stackable micro-credentials that allow workers to move between countries. Second, data management. Grid operations will depend on AI-assisted forecasting and demand-side coordination. Curricula in statistics and computer science should incorporate energy systems labs that use real datasets from wind, solar, and EV charging. Third, finance training. Schools of business and public policy should prepare a new generation knowledgeable about green bonds, transition finance, and the risks of financing distributed energy projects. This is where China’s climate leadership provides affordable technology; the talent and funding must keep pace.

Policymakers can secure these advances. The 3,600-gigawatt target suggests that average annual additions need to match or exceed the current rapid pace. This requires significant investment in grid improvements, storage mandates, and interprovincial energy trading. Priority rules should allow solar and wind to be utilized first. Capacity markets should reward flexibility rather than coal runtime. Electric vehicle milestones require charging infrastructure along major transport routes, as well as regulations that support vehicle-to-grid services. On the global stage, the gap left by the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement increases the significance of Chinese diplomacy in sharing standards, testing procedures, and open data for grid management. It also underscores the importance of transparent methane regulations and enhanced domestic carbon market coverage. These actions are not merely symbolic. They lower capital costs, reduce curtailment, and position the 7 to 10 percent commitment as a stepping stone toward larger reductions.

We should expect three criticisms. First, “China sets easy goals.” The evidence suggests otherwise: the country establishes minimum goals and then exceeds them by expanding industry. It surpassed 1,200 gigawatts of wind and solar six years ahead of schedule. Second, “Coal approvals threaten the transition.” High capacity does not necessitate high generation. If policies limit runtime and prioritize clean energy, coal can diminish even with new constructions planned. Third, “Leadership without Paris finance lacks substance.” The solution here is more leadership, not less—particularly in south-south finance and technology transfer. A strong framework for 2026 to 2030 focused on international grid, storage, and transport projects would align China’s global involvement with its domestic priorities and help partner nations transition directly to clean energy. This is the kind of leadership that builds trust when others retreat.

We should evaluate climate leadership using three criteria: Are emissions decreasing? Is clean energy capacity growing faster than demand? Are policies spreading benefits beyond a single country? On all counts, China’s climate leadership now meets the mark. Emissions have been steady or declining since early 2024. Wind, solar, and electric vehicles are proliferating. New targets for 2035 translate into investment plans that benefit suppliers and consumers worldwide. The pledge to cut emissions by 7 to 10 percent by 2035 might seem modest. However, it should be viewed as a baseline. If upgrades to grids, storage systems, and dispatch reforms keep pace, this baseline will rise—and soon. This is especially important in a year when the United States has once again chosen to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Someone must keep the pact functioning in practice. The data from China indicates that it is already happening. The challenge for educators and policymakers is to transform those figures into skilled professionals: engineers, planners, and educators who will make the transition last. This is how a baseline turns into a landmark.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Carbon Brief. (2025, January 27). Record surge of clean energy in 2024 halts China’s CO2 rise.

Carbon Brief. (2025, May 15). Clean energy just put China’s CO2 emissions into reverse for first time.

Carbon Brief. (2025, September 25). Q&A: What does China’s new Paris Agreement pledge mean for climate action?

Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. (2025, September 10). Decoding China’s upcoming climate targets.

DNV. (2025, October 15). Energy Transition Outlook 2025.

Ember. (2025, September 9). China Energy Transition Review 2025.

Global Energy Monitor. (2025, April 3). Boom and Bust Coal 2025.

International Energy Agency. (2025, March 23). Solar PV and wind net additions in China, 2023–2024.

International Energy Agency. (2025, May 14). Global EV Outlook 2025.

International Energy Agency. (2025). Solar PV – Energy system overview.

International Energy Agency. (2025). World Energy Investment 2025: China.

NewClimate Institute. (2025, Nov.). Progress of major emitters towards climate targets.

Reuters. (2025, January 20). Trump to withdraw from Paris climate agreement, White House says.

Reuters. (2025, September 25). China sets renewables goal it can easily surpass, analysts say.

S&P Global Commodity Insights. (2025, October 14). China’s NEV sales rise to year-to-date high in September.

The Guardian. (2025, November 11). China’s CO2 emissions have been flat or falling for past 18 months, analysis finds.

White House. (2025, January 20). Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements [Executive Order].

World Resources Institute. (2025, September 24). Statement: China Announces New Climate Target.

Xinhua. (2025, September 25). Xi announces China’s 2035 Nationally Determined Contributions.

Comment