After Hegemony: Why Japan's New Pluralism Could Reshape Learning as Much as Politics

Input

Modified

LDP hegemony breaks; multipartism rises Japan political diversification is reshaping education Act now: language support, student metrics, local compacts

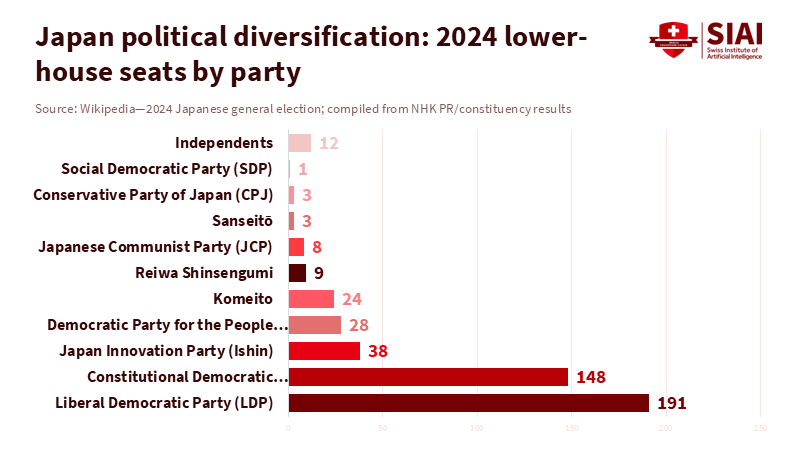

Japan's politics are not just shifting to the right; they are changing dramatically. In the 2024 lower-house election, the long-dominant LDP fell to 191 seats and, along with Komeito, dropped to 215, which is below the 233 needed for a majority. Voter turnout was only 53.8%, the third-lowest since World War II, but the message was clear: voters chose more parties than ever since 1955. This shift opens new opportunities for diverse representation and policy innovation, encouraging optimism about Japan's evolving political landscape.

The simplest story is about a move to the far right. The more complex—and accurate—story is about Japan's political diversification: a rapid shift from single-party control to a competitive, multiparty environment in which both the right and the left have stronger voices, and policy is determined through negotiations rather than factional deals. This shift is significant for education as much as for budgets, taxes, and foreign policy. When the political landscape changes, the education system often follows suit.

Japan's political diversification, not collapse

The end of automatic LDP majorities does not mean chaos; it means choice. The 2024 general election forced the LDP into minority government for the first time since 2009. The CDP achieved its best performance, smaller parties gained, and, for the first time in seventy years, no party claimed more than 200 seats. In 2025, the ruling coalition lost control of the upper house as well, establishing a two-chamber reality in which policy requires cross-party agreements. This environment promotes a culture of negotiation, which can build confidence in Japan's capacity to adapt and govern effectively.

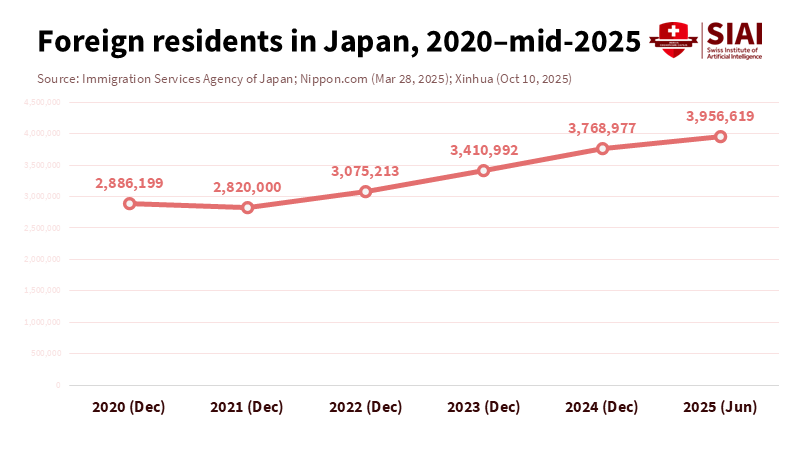

This new landscape is evident in the demands of elected representatives. For example, in July 2025, a record number of women entered the upper house, including candidates from conservative and nationalist parties. This is not just a slight ideological change; it indicates that candidate pipelines, party identities, and voter expectations are broadening simultaneously. Japan's political diversification is also demographic: by mid-2025, the foreign resident population had grown to about 3.95 million—roughly 3.2% of the total population—intensifying discussions on migration, skills, and local services. These structural changes make it less likely that any party will maintain lasting dominance. They also create policies that are more flexible and potentially more responsive.

The question is not whether the right is more vocal. It is whether the new party structure becomes polarized or fosters a culture of negotiation. The answer depends on how mainstream parties address critical issues—especially immigration, cost of living, and defense—without framing them as extreme identity choices. The Takaichi government's approach may push the LDP further right in the short term. Still, in a fragmented Diet, this move may isolate the party or help form new coalitions.

How far-right gains fit a broader realignment

Sanseitō's rise is significant. In the 2025 upper-house election, the party used "Japanese First" messaging to grow from a minor influence into a substantial bloc, appealing particularly to young men and making anti-immigration issues mainstream. However, focusing only on Sanseitō overlooks the bigger picture: the same election also spotlighted centrist groups like the Democratic Party for the People and strengthened left-populist movements like Reiwa Shinsengumi. The right gained, but so did other parties. This trend aligns with what researchers term "Europeanization": more women in office, more relevant parties, and a normalized far-right presence competing alongside stronger center-left alternatives.

Immigration is crucial in connecting these trends. Japan's foreign resident population has increased for three consecutive years, driven by labor shortages and the return of mobility after the pandemic. The government itself recognizes this pressure by setting up a cross-agency "control tower" to address crime, tourism, and local service concerns. Yet the facts complicate the narrative. Foreign residents account for just over 3% of the population, even as employers warn of long-term labor shortages. OECD data indicate that Japan has reopened its borders to students and workers rather than closed them. In other words, Japan's political diversification relies on demographic changes. As more communities depend on foreign talent and tuition, more parties compete to address this reality for concerned voters.

None of this suggests the end of the LDP era. The party could regroup under pressure, shift a tough security stance into broader economic appeal, and regain a working majority—especially if opposing parties revert to mutual blockades. However, even a restored LDP-led government would operate in a different context: with more women in the Diet, stronger nationalist voices, and centrist groups able to negotiate policy concessions. The far right may have gained a louder voice, not a mandate; its endurance will rest on whether mainstream parties adopt its arguments or provide concrete, reliable benefits.

Japan's political diversification in schools and universities

Education plays a key role in this transition. Universities are becoming linked with migration policies and regional revitalization. With over 160,000 new international student permits issued in 2022, these students support budgets, fill lab spaces, and boost local economies from Sapporo to Kyushu. Japan's political diversification means that discussions about these flows will involve more parties with distinct viewpoints: some may advocate for stricter borders and "cultural coherence," while others may propose fast-track residency for STEM graduates and targeted support for immigrant families. Where a dominant party once set expectations, educational institutions now face a constant stream of coalition agreements that may alter rules on admissions, curricula, and governance with each parliamentary session.

Schools will experience similar tensions. New civics standards may shift between a more assertive nationalism and a pluralist approach that prioritizes media literacy and debate. Local school boards, already under strain, will need to engage with growing numbers of foreign-resident families while facing pressure from both anti-immigration efforts and business groups seeking skilled workers. The risks are apparent: culture-war agendas can overshadow practical reforms regarding class sizes, teacher salaries, and digital infrastructure. The potential is equally clear: when multiple parties need to show results, education offers opportunities for productive compromises that can deliver visible benefits within a single school year.

A practical coalition path is readily available. Parties across the spectrum can agree on three immediate steps: increase high-quality, low-cost language support for newcomer families in municipalities experiencing rapid growth in foreign populations; fund campus-industry collaborations that convert international student inflows into regional retention; and shield classroom time from shifts by establishing fixed multi-year cycles for curriculum reviews. None of these actions requires constitutional upheaval. All of them can turn coalition discussions into tangible results that parents will notice.

Concerns, responses, and what to do before the next election

Two main critiques dominate the discussion. The first claim is that Japan's political diversification is an illusion, asserting that LDP factionalism still dictates policy. The evidence contradicts this claim. A government without a majority in the lower house, and then in the upper house, must seek votes openly. The results from 2024 and 2025 forced the LDP to seek allies on a policy-by-policy basis; even its leadership changed within a year, highlighting real external pressures on the party. The second critique argues that far-right gains will create a stagnant divide. This is a risk, yet the same elections increased female representation and broadened opportunities for centrist negotiations. These realities challenge a simplistic narrative of despair.

Educators and administrators should not wait for coalition dynamics to stabilize. Three actions are achievable now. First, enhance evidence-based civic education. Students should engage with current issues in today's Diet—such as immigration thresholds, regional university funding, and data privacy laws—and learn to evaluate claims using public data. Second, recognize international education as a key resource. Universities can publish yearly reports showing the financial and research benefits of international student enrollments, making it easier for any coalition to support sensible visa policies. Third, foster local agreements. Mayors, school boards, and university leaders can pre-negotiate initial packages—such as language support services, teacher recruitment goals, and internship guarantees—that any national government could modestly fund and expand. In a multiparty system, policies that are affordable, quick, and visible tend to prevail.

There is also a lesson in messaging for national leaders tempted by sensational headlines. Voters rejected scandal and inaction in 2024; they favored parties that offered solutions about pay, prices, and services. Increased competition among parties can heighten tensions but also raise the expectations for effective governance. When every seat counts, the quality of schools in the next district matters more than campaign slogans in the next news cycle.

The key takeaway is clear: Japan's voters broke free from a history of hegemony. They redistributed power among the right and the center. They left and compelled the LDP to share authority—first in the lower house, then in the upper house. The far right has a voice; so do women and centrists in unprecedented numbers. Demographic pressures will persist: foreign residents already make up more than 3% of the population, and the influx of international students and workers will continue to rise if Japan aims to address its labor shortages. The question for education is whether we view Japan's political diversification as a challenge to withstand or a new normal to embrace. The response should be practical and immediate. Implement affordable, high-impact educational supports that any coalition can approve. Present clear metrics from universities that demonstrate the benefits of openness. Teach students to argue and listen within a genuine multiparty democracy. If we take these steps now, the next election will not only assess power but also reveal whether Japan has learned to govern effectively.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Agence France-Presse / The Guardian. (2025, December 2). Japan PM's pledge to 'work, work, work, work, and work' wins catchphrase of the year.

AP News. (2025, July). Ishiba's coalition loses majority in Japan's upper house election.

East Asia Forum. (2025, December 3). The end of LDP hegemony in Japan.

ECPR—The Loop. (2025, September 17). More women, multipartism, and far-right populism—Is Japan becoming more 'European'?

European Parliamentary Research Service. (2024, October 22). Japan towards 2024 general elections.

Le Monde. (2025, July 25). Record number of women elected to Senate shows rise in political presence.

Nippon.com. (2025, March 28). Japan's foreign population hits 3.8 million.

Nippon.com. (2025, July 24). Sanseitō makes a splash: Populist politics on the rise in Japan.

OECD. (2024, November 14). International Migration Outlook 2024—Japan chapter.

Reuters. (2024, October 28). Japan's government in flux after election gives no party majority.

Reuters. (2025, July 20). 'Japanese First' party emerges as election force with tough immigration talk.

Reuters Breakingviews. (2024, October 28). Election throws Japan into turbulent waters.

Xinhua. (2025, October 10). Japan's foreign population hits record 3.95 million.

Wikipedia. (2024, updated). 2024 Japanese general election.

Wikipedia. (2025, updated). 2025 Japanese House of Councillors election.

Comment