Europe's New Defence Bill Can't Come Out of the Classroom

Input

Modified

Europe may move to 5% defence Use EU bonds, cut weak subsidies, and buy jointly Ring-fence education and expand skills

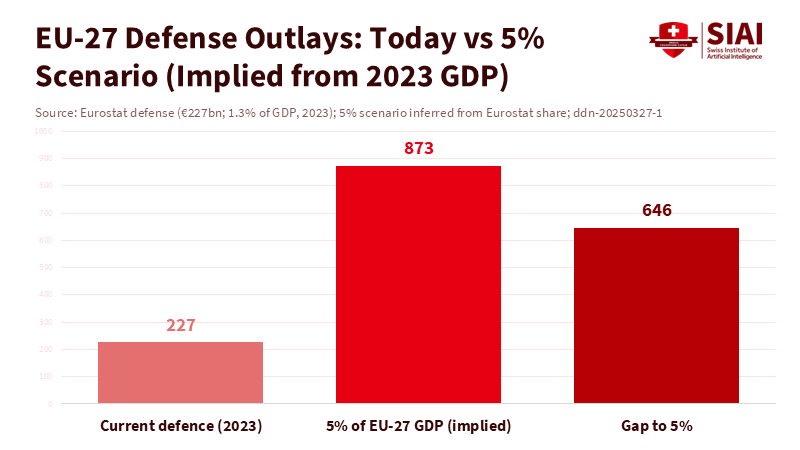

Europe is being asked to plan defence spending at 5% of GDP. For the EU-27, this amounts to about €895 billion a year, based on an estimated 2024 economy of €17.9 trillion. Current EU government defence expenditures were around €227 billion in 2023, which is only 1.3% of GDP, creating a massive gap. This situation could become politically volatile if citizens believe that the only solution is to cut education and social services. The choice isn't "guns or classrooms." It is "smart European defence financing or a social fracture." By 'smart European defence financing', we mean a strategy that is efficient, effective, and sustainable, and that enables financing security while also supporting social mobility—if Europe reduces wasteful subsidies, shares funding at the EU level, and establishes rules to protect schools. Meanwhile, Russia spends about 7% of its GDP on its military, so that any delay could be costly. Europe must act, but it needs to proceed cautiously.

The price tag of European defence financing

Let's consider the scale. NATO's European members recently reached the old 2% target, investing about $380 billion in 2024. At the same time, EU government defence expenditures reported by Eurostat hit €227 billion in 2023. Although definitions differ, with NATO's measure being broader than Eurostat's COFOG accounts, increasing spending to five percent would require at least doubling, and in some cases tripling, current efforts. This is why leaders are now discussing a 5% path by the mid-2030s, with 3.5% dedicated to core military needs and 1.5% for resilience—from cyber to critical infrastructure. By 'resilience', we mean the ability to withstand and recover from potential threats and attacks, including those in the cyber and physical domains. The headline figure is stark; the path must remain steady.

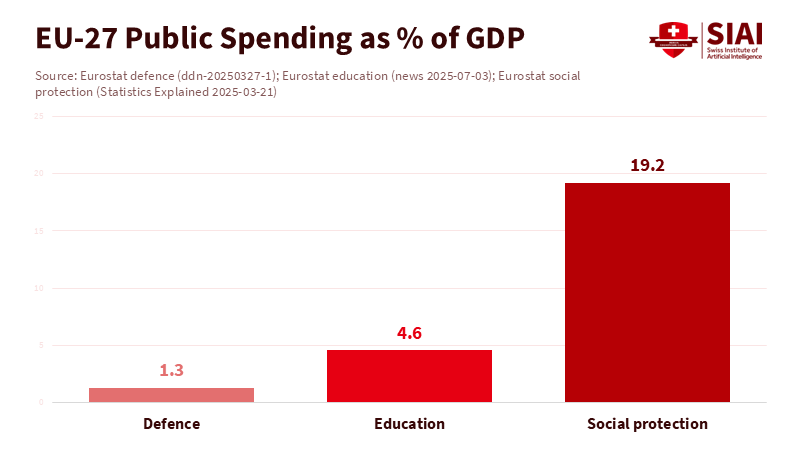

Put that 5% into context. Social protection currently accounts for the EU's most significant budget function, representing 19.2% of GDP in 2023, with pensions and sickness benefits as the most critical components. Education spending averages around 4.6% of GDP in the euro area, with France at 5%—these investments anchor opportunity and stability. A quick shift from social protection and education to defence would lead to visible suffering and political backlash. It would also undermine the skilled workforce that the defence sector relies on to handle new orders. The goal should be to add capacity, not swap it out—by using a broader European balance sheet and smarter tax policy.

The other side of the ledger is Russia. According to SIPRI, Russia's military spending increased by 38% in 2024 to about $149 billion, which is around 7.1% of GDP. Europe doesn't need to match that level of spending, and it shouldn't. Europe's economy is much larger; well-governed, targeted spending can create significant capabilities without the distortions typical of a wartime economy. The aim should be credible deterrence at a sustainable cost—not a budget race to Second World War levels, when the UK pushed defence spending above 50% of GDP.

European defence financing without gutting schools and care

Three immediate financing options can protect education. First, consider common issuance. CEPR economists propose a catch-up envelope of around 1% of GDP per year for ten years at the EU level—about €2 trillion total if all EU nations participate—via joint Future of Defence bonds that the ECB would recognize. Spreading costs over time and across countries lowers borrowing costs, creates a genuine euro-safe asset, and brings capabilities online sooner. This aligns with the Commission's European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS) and the EU's recent procurement initiatives. It also echoes the EIB's recent shift to finance more dual-use projects following its 2024 policy update.

Second, reforming tax expenditures could yield significant funds. The Commission's latest analysis shows that reduced VAT rates cost about 1.1% of GDP, and personal income tax expenditures average around 1.2%. Not all of these funds are available for realignment. However, selectively eliminating poorly targeted tax breaks could raise tens of billions annually without cutting essential services. Coupling this with stricter sunset provisions and reviews would create lasting yields. While the political landscape is rugged, the math is solid.

Third, phase out crisis-era fossil-fuel subsidies and align energy support with the need for defence-energy security. The Commission reports that direct fossil-fuel subsidies grew to €136 billion in 2022, then eased to €111 billion in 2023. The European Environment Agency confirms that much of this support is time-limited; however, around half of it does not yet have an end date. Establish a deadline, redirect savings to defence and to targeted assistance for lower-income households, and Europe can fund security while accelerating the transition to clean energy and reducing reliance on Russia.

European defence financing needs a joint balance sheet

Markets also take notice of governance. Fragmented national orders inflate costs and delay deliveries. The EU has begun to address this with ASAP to ramp up ammunition production and EDIRPA to encourage joint procurement. Yet the current scale remains small compared to the need, and the backlog of promised orders is extensive. A joint purchasing office, supported by common bonds and based at a re-mandated ESM or a new agency, could issue multi-year tenders, allowing European industry to expand capacity confidently. This approach can drive down costs and attract private capital, even as the EIB broadens support for dual-use projects.

The larger geopolitical context is clear. With Washington indicating that Europe must "pay in a big way" and pushing for a 5% target by 2035, the time for half-measures has passed. In 2024, European NATO members increased defence spending by around 19% in real terms, yet capability gaps persist. Leaders from Paris to Berlin recognize the need for movement; the debate now centers on the balance between national budgets and shared borrowing, as well as the timeline for implementing it. The best solution is a rules-based, EU-level initiative that maintains fiscal credibility and protects education during the buildup.

What this means for classrooms and campuses

Education systems play a critical role in this transition; they can either hinder or facilitate progress. Europe cannot build air defence, cyber capabilities, space technology, and munitions production without tens of thousands more technicians, engineers, data scientists, and skilled workers. This will require safeguarding education budgets in national medium-term plans and steering new training towards fields like mechatronics, propulsion, AI assurance, and secure software. Additionally, it implies utilizing dual-use R&D funding to keep universities central to Europe's defence innovation framework. When done effectively, these decisions can also enhance productivity outside the defence sector. Cutting education would save little in the short term and cost Europe dearly in the coming decade.

Administrators will feel the impact first in local skill pipelines. The quickest wins will come from paid apprenticeships connected to European procurement, embedding micro-credentials in universities for defence-related fields, and shared facilities where SMEs, primes, and labs can test designs. It's crucial to maintain accurate accounting: do not mislabel existing education programs as "defence" to meet the 5% goal. Fund skill development transparently; protect general education; and use targeted bursaries to ensure that advantages reach underserved regions and low-income households. This strategy can ensure that defence growth supports social mobility rather than undermines it.

Anticipating the hard questions

The first argument against this plan is that achieving 5% will require cuts to welfare. It doesn't have to. A balanced approach using common bonds, targeted tax breaks, and an end to fossil-fuel subsidies can raise substantial funds while safeguarding pensions and schools. The trade-offs are real, but the assumption that welfare is the only funding source is incorrect. The dichotomy of War vs. Welfare is compelling politically, but economically flawed; countries already invest significant sums in broad tax breaks with weak social returns. A tighter focus on these areas would create less hardship than cutting education.

The second argument claims that 5% is still insufficient. Historically, wartime economies have exceeded 50% of GDP for defence in extreme circumstances. However, that was total mobilization during a world war, not modern deterrence. Europe's goal is to make aggression prohibitively expensive while keeping the fiscal burden manageable, not to emulate Russia's wartime spending. The key metric should be the delivery of credible capabilities—air defence systems, stockpiles, resilient communications—at the lowest possible cost. This requires joint financing and procurement, not maximum spending shares.

A third argument suggests that Europe should also work to limit Russia's military buildup. It should do this. Deterrence and diplomacy work together. Sanctions that hinder Russia's access to dual-use materials, adequate export controls, and a clear path toward arms-control discussions can slow Russia's military expansion. However, these measures will only be effective if Europe builds its own capabilities first. As long as Russia maintains military spending around 7% of GDP, complacency is a risk.

A workable path—at speed, without self-harm

Europe can secure defence funding without dismantling its social contract. A realistic ten-year plan would look like this: establish an EU-level catch-up package of nearly 1% of GDP through common bonds; gradually increase national defence spending to 3–3.5% through pre-announced steps; allocate the final 1–1.5% for resilience and infrastructure; and firmly protect education budgets in national financial frameworks. Eliminate the most harmful fossil-fuel subsidies, cut ineffective tax breaks, direct EIB funding toward dual-use projects, and utilize joint procurement to help the industry scale confidently. The Commission's suite of tools (ASAP, EDIRPA, EDIS) should serve as the backbone of this strategy, not just pilot projects. While this path requires investment, it is more sustainable than a chaotic scramble—and far cheaper than a crisis.

The overall figure is daunting—€895 billion a year at five percent. However, the real issue is about the structure, not the denial of needs. Europe can finance a credible defence while safeguarding education if it views financing as a European public good, stops funding outdated energy systems, and trims ineffective tax breaks. This approach carries political clout because it is fair and transparent. It meets the urgent need, especially amid Washington's pressure, Moscow's rearmament, and the reimplementation of fiscal rules. The priority now is to move quickly on collective funding, joint procurement, and shared skills—so that the next euros invest in deterrence rather than duplication. If Europe takes these steps, it can avoid falling into a false dichotomy of war versus welfare, honor commitments to families, and build a sustainable security posture. This is the promise of properly executed European defence financing.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, June 25). NATO countries' budgets compared: Defence vs healthcare and education.

Bank of France. (2025). Public spending in France and the euro area. Bulletin 259.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025). European defence governance and financing.

European Commission. (2024). Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP).

European Commission. (2024). EDIRPA—Addressing capability gaps via joint procurement.

European Commission / EEA. (2025). Fossil fuel subsidies in EU Member States: Trends and analytical challenges; Fossil-fuel subsidies indicator update.

European Investment Bank. (2024, May 8). EIB steps up support for Europe's security and defence industry.

Eurostat. (2025, Mar. 27). Government expenditure on defence—€227 bn (1.3% of GDP) in 2023.

Eurostat. (2025). Government expenditure on social protection—19.2% of GDP in 2023.

Reuters. (2025, Apr. 24). NATO's Rutte calls for a "quantum leap" in defence investment.

SIPRI. (2025, Apr. 28). Trends in world military expenditure, 2024 (Fact sheet: Russia ~7.1% of GDP).

Voice of America. (2024, Feb. 15). NATO allies in Europe to invest $380 bn in defence in 2024.

Comment