India, China, and the Future of Asia

Input

Modified

India hedges: the U.S. for markets, China for inputs and leverage Border tensions won’t decide outcomes; economics and supply chains now dominate China’s smart play is targeted import access, guaranteed components, and faster flights/visas

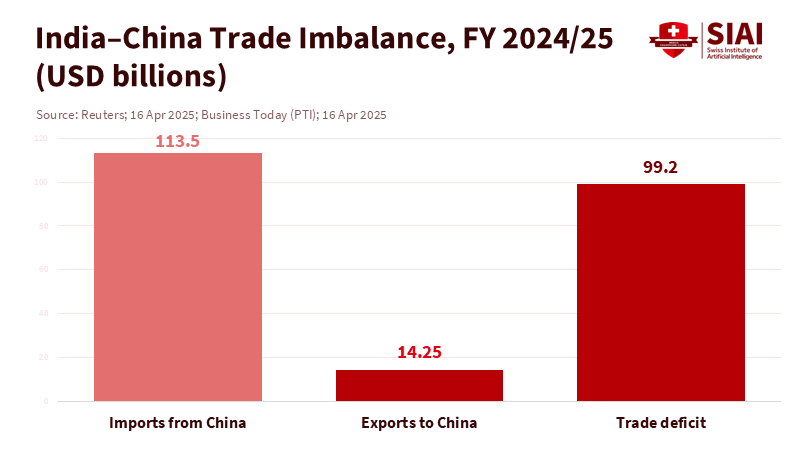

If you're looking for a key figure to sum up the future of Asian geopolitics, consider $99.2 billion. This was India's record trade deficit with China in FY 2024/25. It increased even as New Delhi and Beijing kept large numbers of troops stationed in the Himalayas and exchanged harsh words. In August 2025, Washington further complicated matters by imposing tariffs that raised duties on many Indian goods to as high as 50%, impacting India's largest export market. Still, U.S.-India trade in 2024 reached $212.3 billion—too significant to abandon, yet increasingly fragile. These three facts coexist without conflict. They show that India will not “compromise” emotionally with China. Instead, it will maintain a strict balance: rely on the U.S. for markets and technology, turn to China for raw materials and options, and use each to counterbalance the other. The issue is not whether the border matters; it's whether it will determine outcomes. It won't; economics will take precedence. This places India-China strategic leverage at the heart of the narrative.

Understanding India-China Strategic Leverage

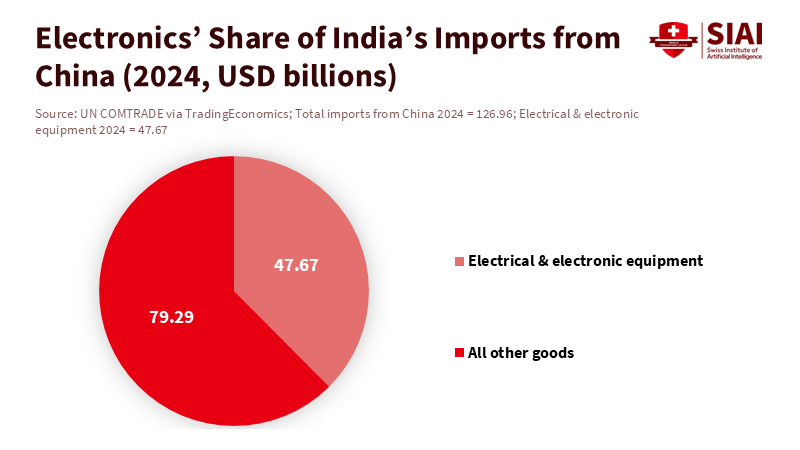

To be clear, strategic leverage here refers to both sides' ability to increase their freedom of action by deepening economic ties in specific, impactful areas while guarding against security risks. India's reliance on Chinese intermediate goods is key. In FY 2024/25, India imported around $113.5 billion from China, primarily in electronics, batteries, and solar materials. These very items support India's manufacturing and green initiatives. In 2024 alone, India imported $47.7 billion worth of electrical and electronic equipment from China. This is not a broad dependence; it's targeted leverage. China can adjust prices, approvals, and shipping times in a few product categories, thereby quickly affecting India's cost structure. India understands this and is working to build domestic capacity and find non-Chinese partners. Still, this shift is incomplete and will remain so for years.

The changes in supply chains that are often highlighted actually reinforce India's strategic leverage. For instance, Apple produced an estimated $14 billion in iPhones in India in fiscal 2024—about 14% of global iPhone production. Yet, the supply ecosystem remains heavily reliant on Chinese materials and expertise. Even India’s attempts to reduce risk create new dependencies: Amara Raja’s 2024 licensing agreement with Gotion (China) to produce lithium-ion cells in India highlights the technology reliance Delhi wishes to manage, not eliminate. This is a clear indication that India needs to manage its technology dependence on China to maintain its strategic leverage. Despite policy challenges, most of India’s photovoltaic cells and modules—or their precursors—come from factories in China’s dominant supply chain. This is why examining India's strategic leverage vis-à-vis China is essential. It reveals how each side can open or restrict key supply chains—such as cells, wafers, battery materials, and precision components—that influence India's growth, and how India can change market access and political recognition in international forums important to China.

Why Border Issues Won’t Define the Relationship

We should stop viewing the Line of Actual Control as the primary variable. New Delhi and Beijing have spent the last four years isolating the crisis rather than allowing it to control the relationship. By late 2024, India’s foreign minister stated that about 75% of disengagement issues had been resolved. In October 2025, both sides began resuming direct flights after a five-year pause—low drama but significant nonetheless. These actions don't settle the dispute, but they reflect a mutual decision to manage the kinetic risks while reopening economic and people-to-people interactions. When conflict no longer drives the timeline, it stops dictating policy.

India has also separated its hard security cooperation from its economic relationship with China. The Malabar 2024 naval exercise involving the U.S., Japan, and Australia proceeded as planned. The foundational agreements—LEMOA (2016), COMCASA (2018), and BECA (2020)—remain intact. India won’t compromise these for a friendlier relationship with Beijing. The key point is that border management and defense strategies operate on one path. At the same time, selective economic normalization with China unfolds on another front. Although tensions may exist, both tracks run parallel to one another. The reality is that Indian factories depend on Chinese inputs today and American demand tomorrow. The border situation can fluctuate, but the constraints remain unchanged.

How Beijing Can Turn U.S.-India Friction Into a Strategic Opportunity

China has an opening because U.S. tariffs have become a political reality. Since August 27, 2025, many Indian goods have been subject to duties of up to 50% in the U.S. India will strive to reduce these tariffs. Still, exporters from labor-intensive sectors—such as gems and jewelry, garments, and shrimp—are already feeling significant pain. Beijing doesn't need major agreements to capitalize on this; it can adopt a disciplined approach of small, practical steps that alleviate India’s tariff burden without requiring Delhi to compromise on security. Three immediate strategies stand out.

First, open targeted import channels. The Tianjin SCO summit included trade facilitation in its agenda and discussed a new SCO Development Bank. China should utilize these platforms to establish tariff-rate quotas and expedite sanitary and phytosanitary approvals for Indian products affected by U.S. tariffs. A narrow, rules-based pathway for Indian shrimp, textiles, and cut-and-polished diamonds could redirect surplus volumes from tariff-hit U.S. markets to China at predictable prices. The goal isn't to “reward” India; it’s to maintain price stability for Chinese consumers and avoid spikes during global supply shifts. Managed access can be adjusted in response to political changes.

Second, secure component-level certainty. China should announce six-month rolling quotas on batteries, wafers, and PCB assemblies for Indian buyers, providing assured delivery timelines and clear pricing structures tied to domestic Chinese indices. Indian exporters of electronics and renewable energy cannot meet production schedules if their inputs are unstable due to U.S. tariffs affecting shipping. A reliable flow of Chinese intermediates would deepen dependence just as India seeks to keep its options open—and it would be challenging to reverse without incurring costs. Beijing has concrete examples to reference, such as the Gotion-Amara Raja cell technology agreement and the well-documented dominance of Chinese firms in upstream solar production. India-China strategic leverage hinges on these “boring” components. Make them mundane and dependable.

Third, enhance people-to-people connections. The resumption of direct flights is a crucial step; it should be expanded. Focus on increasing service frequency on routes such as Delhi–Shanghai, Bengaluru–Shenzhen, and Hyderabad–Guangzhou, where tech and component networks overlap. Introduce expedited business visas for Indian engineers and procurement teams linked to supply contracts. Additionally, broaden education opportunities: the SCO has endorsed deeper cooperation in AI. Develop joint laboratories with Indian institutions on power electronics, battery management, and industrial AI, offering predictable intellectual property terms and scholarships tied to program outcomes. This approach enhances soft power with tangible benefits: familiarity reduces friction in supply chains.

None of this requires trust; it requires discipline. Delhi will keep the Quad partnership active, and Beijing will not abandon its ties with Pakistan. However, a series of measurable transactions—like import quotas, delivery assurances, air routes, visas, and joint research opportunities—can stabilize the political landscape. It also limits the potential for external pressures. A U.S. tariff hike affects India less if China quietly absorbs some Indian exports and ensures a steady flow of inputs that help Indian factories meet deadlines. This leverage comes from logistics, not rhetoric.

Implications for Policy and How to Proceed

For educators and university leaders, the message is clear. Student interest will increase as direct flights are introduced, visas are issued, and research opportunities are created. As flights resume and bureaucratic obstacles lessen, more Indian students will seek admission to Chinese STEM programs. This will create curricular demands at home; Indian institutions will need more practical courses in power semiconductors, electrochemistry, robotics, and production engineering, potentially co-designed with Chinese partners when safe to do so. Likewise, Chinese universities should develop English-language micro-credentials for Indian professionals in supply-chain management and industrial AI. The emerging SCO AI framework offers a chance to collaborate on electric vehicle supply chains and grid integration, ultimately leading to industry placements in both countries. This educational aspect is vital because the future supply-chain connection will be filled with graduates, not just company leaders.

University administrators and local officials should anticipate new city-to-city partnerships: Shenzhen–Bengaluru for electronics; Guangzhou–Hyderabad for pharmaceutical devices and diagnostics; and Shanghai–Pune for machinery. Create agreements that link procurement internships to import quotas and faculty exchanges to lab results. Keep these programs small, specific, and verifiable; then expand what proves effective. On both sides, export credit agencies and regional development funds can co-finance supplier improvements tied to guaranteed deliveries. Beijing’s proposed SCO Development Bank can help manage the risks for multi-city, multi-firm projects with light conditions. The goal is not to announce significant investments; it’s to mitigate risks in the value chain, where delays and defects can significantly affect profits.

Policymakers will call for safeguards, and they are justified in doing so. India should protect critical sectors—telecommunications, power distribution, and port automation—from new dependencies while maintaining investment scrutiny for sensitive acquisitions. China should recognize that agreements like LEMOA, COMCASA, and BECA will remain the foundation for U.S.-India defense relations and adjust its expectations accordingly. What Beijing can reasonably request is consistent enforcement of Indian standards and a limited easing of import restrictions on Chinese raw materials necessary for India’s industry—an idea Delhi is already considering. Similarly, India can sensibly ask for predictable access for specific exports affected by tariffs and timely approvals for components. Both sides can make concessions in less critical areas to gain in more vital ones. This is how India-China strategic leverage can evolve into a stable but pragmatic balance.

Critics might argue that this approach underestimates political risks. What if tensions at the border escalate? What if Beijing intensifies support for Pakistan or Delhi increases engagement with Taiwan? These risks are valid. But de-escalation channels also exist, and they have already achieved partial disengagement and resumed flights. Another concern is that India may drift further toward the U.S., regardless of tariffs. However, the tariff shock has heightened the need to diversify market access—not to exit the U.S., but to buy time and increase bargaining power. Some may believe the SCO is too weak to matter. While it is not a treaty-enforcing body, it provides practical, low-conflict tools like trade facilitation language, an emerging development bank, and a framework for AI cooperation—all of which can anchor manageable gains without forcing either side into ideological commitments.

The final ethical consideration is that neither side should exploit these new pathways to evade sanctions or compromise on labor and environmental standards. If Beijing desires durability, it should tie preferential access to improved compliance within Indian supplier networks—such as ensuring traceability of cobalt and nickel, proper battery recycling, and responsible seafood sourcing. If Delhi seeks legitimacy, it should protect critical technologies while offering honest, timely approvals for other goods. Effective leverage depends on transparency.

Returning to the initial figure, $99.2 billion reflects not friendship but the nature of interdependence. Consider two more points: U.S. tariffs on many Indian exports now stand at up to 50%, and the $212.3 billion trade volume between the U.S. and India is too crucial to disrupt. Together, these factors lead India toward a strategy where China becomes a necessity, not a preferred partner, in specific sectors. For Beijing, the intelligent strategy is not to demand impossible concessions from India. Instead, it should take small, calculated steps: open limited import channels for Indian goods subject to tariffs, ensure a steady supply of components that rely on Chinese inputs for Indian delivery, and expand air travel, visas, and research collaborations to keep the economy running smoothly. By doing this, the border will stop being the ultimate decider; economics will take the lead. This is how India-China strategic leverage will shape the next decade—one quota, one timeline, one flight at a time. The simple call to action is to create these pathways before political circumstances hinder them.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025, August 27). Trump’s 50% tariffs on India over Russian oil purchases take effect.

AP News. (2025, September 1). China’s Xi seeks an expanded role for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization at the Tianjin summit.

Chatham House. (2025, April 23). How China–India relations will shape Asia and the global order (Report).

Government of India, Press Information Bureau. (2024, October 5). Maritime Exercise Malabar 2024—Curtain Raiser.

International Energy Agency & IISD et al. (2024–2025). Battery and solar supply-chain notes for India (selected charts/reports).

MEA, Government of India. (2018, September 6). Joint Statement on the Inaugural India–U.S. 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue (COMCASA reference).

PIB, Government of India. (2016, August 30). India and the United States sign LEMOA.

Reuters. (2024, October 21). The long road to resolving the India–China border stand-off.

Reuters. (2024, April 10). Apple’s India iPhone output hits $14 bn.

Reuters. (2025, April 16). India’s trade deficit with China widens to record $99.2 bn amid dumping concerns.

Reuters. (2025, August 6 & August 27). U.S. imposes extra tariffs on Indian goods; tariffs reach 50%.

Reuters. (2025, October 2). India and China to resume direct flights after five-year freeze.

Reuters. (2024, June 24). Amara Raja inks licensing deal with Gotion for Li-ion cells in India.

TradingEconomics (UN COMTRADE). (2025). India imports from China: Electrical, electronic equipment (2024).

USTR. (2025). India—Trade Summary (2024).

White House. (2025, August 6). Fact Sheet: Addressing Threats to the United States by the Government of the Russian Federation (tariffs on India).

Xinhua/official communiqués via Kremlin archive. (2025, September 1). Tianjin Declaration—trade facilitation language & development bank discussion.

Comment