Stop Chasing Followers: Social Network Bridging Is the Real Power in Education

Input

Modified

Social network bridging beats raw reach for lasting influence in education Bridges and weak ties move jobs, ideas, and credible signals across clusters faster than hubs Name brokers, track cross-cluster reach, and build routines that link communities

The most significant number in today’s discussion about influence is 600,000. That is how many jobs people secured in a five-year LinkedIn experiment that changed who users were nudged to connect with. The outcome was not a win for celebrity hubs; it was a success for bridges. When the platform’s algorithm directed users toward weaker, more diverse connections, mobility increased. Strong ties still mattered for trust, but weak and “moderately weak” ties did most of the work. The study involved about 20 million users and two billion new connections. It provides the clearest large-scale test we have of how influence moves online. The lesson for schools, universities, and education agencies is straightforward. If we want ideas, tools, and practices to spread and endure, social network bridging outperforms raw reach. Build connections across groups, not just bigger audiences.

Rethinking influence: why social network bridging outperforms raw reach

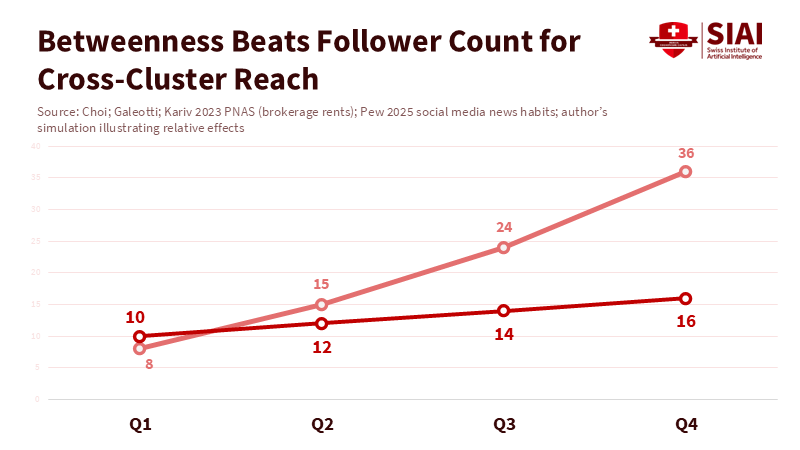

Influence lasts when it connects groups that rarely communicate. That is the advantage of social network bridging. Economic studies show that intermediaries who connect groups capture "brokerage rents." The value goes to the go-between, not just to the most prominent node. In education, this concept is straightforward. Those who connect teachers to researchers, district data teams to school leaders, and parent networks to policymakers facilitate decisions across boundaries. Status helps, but structure is more effective. Bridges reduce friction, create paths, and allow practices to continue beyond flashy launches.

A second body of research highlights the human skill that supports lasting influence. People create "cognitive maps" of their social world. We learn who is connected to whom and anticipate which links will matter next. Experiments show that clear mental maps of a network lead to more intelligent decisions about where to share information and when. Education leaders who can identify clusters and gaps—not just friends and followers—can focus their efforts more effectively. This is not a call for more charm but an argument for network awareness: a clear understanding of how ideas spread among people and places.

The digital landscape raises the stakes. Social media now has an estimated 5.66 billion "user identities," representing over two-thirds of the global population. Users spend about 18 hours and 36 minutes a week on social platforms. In the U.S., about 1 in 5 adults get news on TikTok, rising to 43% among adults under 30. Attention is plentiful yet fragile. In this environment, volume and speed are inexpensive. Bridges, however, are rare. If we care about lasting influence in education, we should prioritize connections between groups rather than mass broadcasts within a single group.

Evidence that bridges travel farther: jobs, ideas, and even gossip

The LinkedIn experiment should reshape how we design professional development. It shows at scale that weaker, bridging ties lead people to more opportunities. This idea also applies to information. Studies of information diffusion find that networks with paths crossing communities share content more widely and effectively. New research even models how weaker ties can facilitate quicker communication when platforms are crowded. This is the approach we need when we want a promising reading program, a new assessment, or a credible AI classroom policy to extend beyond early adopters.

The tricky word in this discussion is "gossip." We often view it negatively, but research offers a more nuanced outlook. People infer motives from second-hand information. If the motive seems constructive—like warning, ensuring quality, or setting norms—gossip can encourage cooperation. Recent studies indicate that group identity influences how we react to gossip and whether we act on it. In education, this looks like everyday practice: an instructional coach shares a discreet warning about a flawed edtech tool, a department lead shares a trusted classroom resource, or a mentor highlights a reliable dataset. Gossip is not the primary goal; routing is. We can improve those routes by bridging communities and grounding claims in evidence.

However, there is a warning. Bridges can also carry misinformation. Studies from 2024–2025 show that highly central nodes lacking individual learning can amplify false information. Reviews indicate that health content often shares misleading claims, and that platform algorithms can favor sensational posts. This doesn’t mean we should close networks; it means we should build bridges with safeguards: link to sources, invite a credible skeptic outside the group, and monitor whether corrections travel as far as the claims. The architecture of information sharing still favors bridges. The challenge is to guide what they carry.

Social network bridging for schools and systems: from slogan to schedule

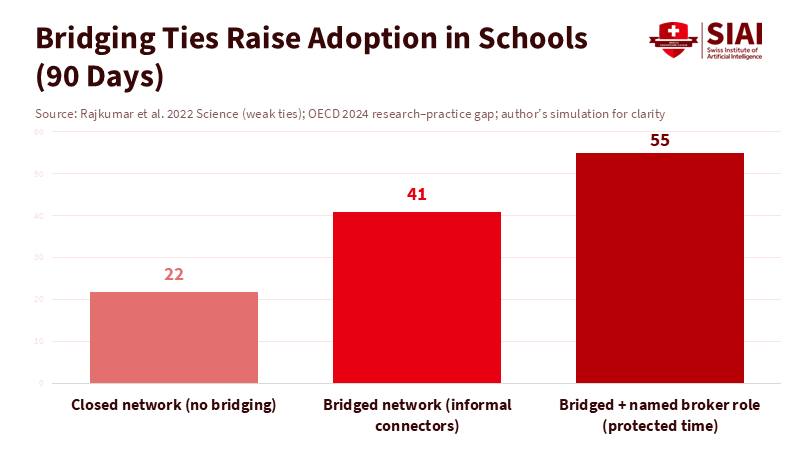

Education has a term for the bridging role: knowledge brokering. Reviews and case studies from 2023–2025 argue that brokers who connect research, practice, and policy increase the likelihood that good ideas spread and take root. They translate findings, match problems with evidence, and carry useful stories across organizational boundaries. Teacher educators can connect classroom practices with broader research. System-level “What Works”-style centers and district research offices can establish repeatable paths so knowledge doesn’t disappear with staff changes. Social network bridging is vital to this work.

What should leaders do now? First, assess the network. Map the communities that need to connect—schools, departments, families, civic groups, and vendors—and designate a credible liaison for each pair. Second, formalize the role. Allocate time for “evidence leads” in schools and districts to connect people and resources across boundaries. Third, measure bridges instead of just broadcasts. Track whether practices cross groups: did an intervention move from one grade band to another, did an edtech pilot reach beyond early adopters, did early-career teachers connect to the collaboration core? Research shows that more open, inclusive networks sustain improvement better than closed ones.

Finally, consider platform incentives. Transparency matters because it shapes what we can see and verify. When tools like CrowdTangle are limited, it becomes harder to trace how content spreads and identify successful or failing bridges. Education agencies should respond in two ways: use open data when possible and create internal analytics to monitor cross-community flows rather than vanity metrics. If we want strategic influence, we must focus on connections, not just responses.

Fixing broken playbooks: metrics and habits for social network bridging

The standard advice on how to be influential online still positions influence as a content factory. Typical checklists suggest posting more, chasing engagement, stacking hashtags, and teaming up with “bigger” accounts. That playbook has value, but it’s incomplete. It undervalues network position and bridging. It prioritizes reach over connections. A typical corporate blog defines influence with followers, engagement, authority, impact, conversion, and brand mentions. These metrics matter for marketing, but do not show whether your ideas reached beyond your circle. An education system aiming for lasting impact must ask a different question: did our work cross the boundary that prevents adoption?

This requires a new routine. When you share a resource, include two bridging links in the first comment: a practitioner case from a different community and an external study supporting the claim. When announcing a program, tag one partner outside your usual network and one credible skeptic. When running a webinar, allow time for cross-community Q&A and save the best exchanges as shareable clips featuring both voices. When writing a policy note, collaborate with a teacher or parent advocate from outside your area, then publish in a venue used by both audiences. The goal is clear. Each purposeful bridge opens opportunities for adoption and decreases the chance that good ideas falter within a group.

We also need better dashboards. Replace “top posts” lists with “crossing reports” showing which items moved from researchers to teachers, from teachers to families, and from pilots to policy. Use platform-agnostic measures, as audiences are often fragmented and multi-platform by nature. Global data indicates that people use an average of about seven social platforms each month. This makes building bridges rather than focusing on dominance on one platform the sensible approach. The task is to establish repeatable connections and reward those who keep them open.

Influence in education should be evaluated by movement, not just noise. We began with 600,000 jobs linked to a change in how a platform connected people. The same principle can help ideas and practices flow when we incorporate social network bridging into our routines. Bridges enable mobility. Bridges transmit credible signals across barriers. Bridges allow local experiments to have a broader impact. The risks are real: bad information can use the same routes. But the solution is not to close networks; it is to improve routing. That involves having brokers with time and authority, dashboards to monitor pathways, and habits encouraging connections beyond our circles. If you lead a school, promote bridging. If you teach, create assignments that cross groups. If you research, collaborate with a practitioner, and publish your work, so that both audiences will see it. Influence is not a trophy; it is a system for movement. Build the connections that others will follow.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Choi, S., Galeotti, A., & Kariv, S. (2023). Brokerage rents and intermediation networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(28), e2301929120.

DataReportal. (2025, Feb. 5). Digital 2025: Global overview report (online time and social media time).

DataReportal/Kepios. (2025, Oct.). Global social media statistics (5.66 billion user identities; weekly social media time).

Imada, H., Toyokawa, S., & Takagi, S. (2024). Group-bounded indirect reciprocity and intergroup gossip. Journal of Economic Psychology.

Knight, R. (2024). Teacher educators as knowledge brokers: Reframing knowledge co-construction with school partners. Professional Development in Education.

OECD (Hartmann, U., & Decristan, I.). (2024, July 5). Bridging the research-practice gap in education (EDU/WKP(2024)14).

Pew Research Center. (2025, Sept. 25). Social media and news: Fact sheet (news use on TikTok).

Rajkumar, K., Saint-Jacques, G., Bojinov, I., Brynjolfsson, E., & Aral, S. (2022). A causal test of the strength of weak ties. Science, 377(6612). (Press summary: MIT News).

Son, J.-Y., Bhandari, A., & FeldmanHall, O. (2023). Abstract cognitive maps of social network structure aid adaptive inference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(47), e2310801120.

The Wall Street Journal. (2024, Mar. 14). Meta to replace CrowdTangle and limit public access to data.

Comment