The New Tripod? Why a Germany-Japan Security Alliance Won’t Repeat the 1930s

Input

Modified

Military spending is surging, and the Russia–China axis tightens A Germany–Japan security alliance is lawful, networked, and unlike the 1930s Link logistics, energy, and industry to turn budgets into credible deterrence

In 2024, the world spent $2.718 trillion on the military, a 9.4% increase in just one year. This sharp rise is a wake-up call. It indicates that the strategic landscape is shifting rapidly. This is why a Germany-Japan security alliance is no longer just an idea; it is a practical response to a more dangerous world. The reasons are clear. Russia is at war and rebuilding its military. China is arming heavily and asserting its claims from the Taiwan Strait to the South China Sea. Energy and chip supply chains have become tools of state control. In this context, Berlin and Tokyo are opting for coordination instead of nostalgia. The real question is not whether this resembles the 1930s, but how to forge a modern alliance that deters aggression without repeating the mistakes of that era. The evidence suggests that it is both possible and necessary.

Why a Germany-Japan security alliance is not a replay of the 1930s

The context has changed. Today’s collaboration relies on clear laws, open markets, and alliance networks, rather than on revisionist ambitions. Germany met NATO’s 2 percent military spending target in 2024 for the first time in decades. Japan activated its logistics pact with Germany—the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement—in July 2024. The two air forces conducted joint training during Japan’s Nippon Skies exercise, featuring German Eurofighters and an A400M. These actions go beyond mere symbolism. They represent legal and operational connections that enable two distant democracies to share fuel, parts, and data quickly. The goal is to improve resilience, not to form blocs without purpose. When we examine intentions, structures, and transparency, the comparison to the 1930s falls apart. Instead, we see a network of middle powers designed to manage risks, coordinate with the United States, and maintain peace. The United States plays a crucial role in this alliance, providing strategic alignment and additional deterrence against potential aggressors.

Operational strategies also differ from the past. Germany is now rotating air and naval forces to the Indo-Pacific and has sent two warships to the Pacific. Berlin’s defense minister emphasized the importance of this, as a significant portion of Europe’s trade passes through the South China Sea. In 2024, two German vessels even navigated the Taiwan Strait, sending a careful but clear message that navigation rules still matter. Japan is also increasing exercises with European air forces, and its defense reforms focus on improving readiness rather than pursuing an empire. The outcome is not a closed-off alliance. It is a collection of compatible practices that connect Europe and Asia in practical ways—from refueling to sharing radar data—ensuring that crises do not disrupt global trade. The idea of deterrence can seem harsh. However, the approach is straightforward: training, logistics, and legal agreements. That is precisely why it is effective.

Energy and industry: the foundation of a Germany-Japan security alliance

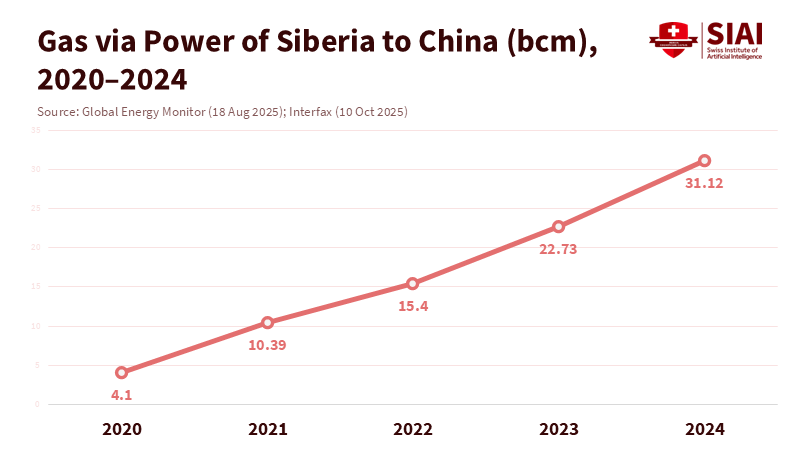

Security hinges on energy and industry. The Russia-China partnership is crucial here. Two statistics illustrate this point. Bilateral trade reached $240.1 billion in 2023, and Chinese imports of Russian crude hit a record 108.5 million tons in 2024. Discounted Russian oil and increased gas flows—31.12 billion cubic meters through Power of Siberia in 2024—provide Beijing a cost advantage as it leads in batteries, chemicals, and steel. This undermines Europe’s high-end manufacturing and heightens Japan’s risks regarding shipping lanes and energy import routes. Thus, a Germany-Japan security alliance involves both economic ministries and defense teams. If the energy price gap continues, industrial capabilities will shift, affecting the balance of power. Policy must address this gap through joint LNG strategies, grid-level storage initiatives, and scalable hydrogen projects. Otherwise, the alliance invests in ships and jets while neglecting the factory floor.

Methodology becomes essential when the data is inconsistent. The trade figure comes from China’s customs data as reported by Reuters. The crude number counts both pipeline and seaborne shipments in metric tons. It converts them to barrels per day using standard methods. The gas figure aggregates Power of Siberia deliveries, as tracked by independent sources based on Gazprom's reports. The trends—more oil, more gas, closer technological ties—are consistent across sources. The implication is clear. If Russia’s discounted fuels keep Chinese import costs low, the pressure on German machinery, automobiles, and chemicals will grow. This, in turn, restricts budgets for defense and education at home. Japan faces a similar risk: increased energy import costs and vulnerability to chokepoints around Okinawa and Taiwan. Therefore, the alliance must encompass not just ships and jets but also coordinated industrial policies and energy security planning to narrow the cost gap.

From symbolism to steel: making a Germany-Japan security alliance operational

The first step is to establish scalable habits. Use the 2024 ACSA as a foundation for annual, alternating logistics drills focusing on fuel, munitions, and maintenance in both regions. Link German air deployments under “Pacific Skies” to Japanese air defense scenarios and integrate procedures for fuel support and spare parts. Create a unified checklist for port visits, customs, and communication so task groups can dock in Yokosuka, Sasebo, Hamburg, or Wilhelmshaven with the same documentation and encrypted radios. This may not be glamorous, but it saves valuable time in critical situations. Set goals in months, not years. Document after-action reviews and resolve issues before the next rotation. This is how alliances become strong.

The second step concerns defense industry collaboration. Japan aims to increase defense spending to 2 percent of GDP by 2027. NATO allies have also established a new, long-term financing plan to boost overall defense spending and core capability investment by 2035. Use that budget reality to go beyond one-time joint projects. Select two key projects with short timelines: air-defense interceptors for base protection and autonomous mine-countermeasures for the Baltic Sea and East China Sea. Both are feasible, scalable, and needed. Add cyber training facilities that share malware information from the first island chain in Europe and Asia. On the maritime side, collaborate with Australia, the UK, and the US in AUKUS Pillar II technology projects, where Japan is already an observer. Standardize interfaces so that German and Japanese drones, sonar systems, and electronic warfare pods can connect to the same data infrastructure. This is how to convert budgets into deterrence.

Anticipating critiques and addressing them with evidence

One critique is that closer Germany-Japan ties might provoke Beijing and Moscow. Data support the counterargument. Military spending is rising worldwide, with Europe seeing significant increases. Germany’s rise to 2 percent of GDP in 2024 followed years of delay, not haste. Japan’s actions follow its updated 2022 security policy. They are still carefully measured, with a plan to reach 2 percent by the middle of the decade. This is not an escalation for the sake of it; it is a necessary adjustment to a more dangerous world. The data indicate that Russia’s military spending remains high and sustained, while China’s oil and gas purchases from Russia are increasing. Doing nothing would not change these facts. Taking action—through quiet drills, standardized equipment, and dependable logistics—reshapes potential adversaries’ risk assessments without engaging in combat. That is the goal.

Another critique suggests that Europe should focus on internal issues. At the same time, Asia forms its own coalitions, leaving Washington to connect the two. This perspective underestimates the interconnection between trade and security. Forty percent of Europe’s international trade passes through the South China Sea. Disruptions there would impact German, French, and Italian factories within weeks.

On the other hand, a major war in Europe would consume US resources, munitions, and attention, increasing risks in East Asia. The alliance serves as a safeguard against both scenarios. It also assists Washington by sharing the burden. AUKUS Pillar II is already looking into Japanese participation in specific technologies. Coordinated German-Japanese efforts in air defense, unmanned systems, and underwater surveillance would support that trend. They do not compete with NATO or the US-Japan alliance; they connect with them. That is the aim.

Let’s revisit the figure that started this discussion: $2.718 trillion in one year. The increase was sharp, widespread, and real. We can see it as a grim countdown, or as a push to rethink how we secure peace. A Germany-Japan security alliance is not a return to the 1930s. It is a modern, lawful, and connected solution to a Russia-China alliance that merges warfare, energy, and industry. The tools are already in place: a logistics pact, air and naval rotations that shorten response times, and budget plans that enable middle powers to take on more responsibilities. The current focus is on concrete actions—turn exercises into regular practices. Turn practices into production. Turn production into deterrence that is recognized in Moscow and Beijing, and perceived by educators and leaders at home as an impetus to invest in essential skills: languages, engineering, energy systems, and cyber defense. If we coordinate policy, industry, and education around that goal, the next trillion dollars will buy stability instead of fear.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Airbus. (2024, August 2). Pacific Skies 24: How Airbus serves air forces around the world.

Australian Department of Defence. (2024, November 16). Australia–Japan–United States Trilateral Defense Ministers’ Meeting: AUKUS Pillar II cooperation with Japan.

Bundeswehr. (2024, April 16). Pacific Skies 24 – one deployment, five exercises.

FOI – Swedish Defence Research Agency. (2024, December). Germany in the Indo-Pacific (FOI Memo 8746).

GEM – Global Energy Monitor. (2025, August 18). Power of Siberia Gas Pipeline.

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2024, July 12). Agreement on the Japan-Germany Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement enters into force.

NATO. (2025, June 25). The Hague Summit Declaration.

NATO SHAPE. (2024, July 25). Germany flies in combined drills with Japan during Nippon Skies.

Nippon.com. (2025, June 27). Japan targets 2% defense spending.

Reuters. (2024, May 7). Germany sends two warships to Indo-Pacific amid China and Taiwan tensions.

Reuters. (2024, January 11). China-Russia 2023 trade value hits record high of $240 billion.

Reuters. (2025, January 20). Germany met NATO 2% defence spending target in 2024, defence ministry says.

Reuters. (2025, January 20). China’s crude oil imports from Russia reach new high in 2024 (108.5 Mt).

SIPRI. (2025, April 28). Trends in world military expenditure, 2024 (Fact Sheet).

Comment